11 Ways of Looking at Pleasure

"What Happens to Pleasure When You are Already Dead?"

Now, take my glasses away, snap them in half, and demand that I look, and pleasure—the word—blurs fuzzily. I see the names of the extinct: plesiosaur, an ocean reptile that had a long, ropelike neck and a tiny head, and lived during the Jurassic period; or pleurocoelus, which was once the official state dinosaur of Texas. Or, because I’m only getting worse—between the diplopia, nystagmus, and deterioration of my vision over the last five years—when you tell me to look again, the second half of the word jams and smears and gives the appearance of repetition and I see Peterville, a town on Prince Edward Island, an inn in the United Kingdom, a hotel in Saint Petersburg. Blink: Peterbilt. Blink again: Pleasantville, of which director Gary Ross said, “This movie is about the fact that personal repression gives rise to larger political oppression.”

*

“Pleasure—1: desire, inclination; 2: a state of gratification; 3a: sensual gratification, 3b: frivolous amusement; 4: a source of delight or joy.” Comes from the Old French plaisir, which means “to please,” changed in Middle English to plesure. Think: content, delectation, delight, enjoyment, gladness, gratification, happiness, satisfaction. Depending on your pleasure, it rhymes with glazier, leisure, measure, and treasure.

*

As a little kid, I lived in a Wonderland where pleasure did not exist. Tipped forward over my tricycle’s handlebars, chipped a front tooth. Tripped and fell face-first on a cooling iron’s point, the metal piercing the skin just inches from my eye. Pleasure was unknowable to me, yes, but I also refused to believe it was enjoyed by anyone else—in my child’s eyes pleasure just wasn’t. The lights in the room are either on or off. Because I could not stand being touched, I assumed everyone around me must feel the same way.

That freckle-necked boy being hugged tightly by his father hates it—ignore the smile stretching his face! It is fake, hollow, a grimace if you really look—because being enveloped like that makes his insides coil and slither. Tearing long shreds of paper from each gift, the pink-crowned birthday girl wears a mask of happiness. What she feels, I know, is nothing, is whatever, is I am so tired of this, of all these people. Everyone eats the layered chocolate cake with a scoop of vanilla ice cream and always it is so sour with raw eggs, so sweet sweet sweet, that I, like everyone around me in our stupid tasseled hats, cannot stomach another bite but always stuff another forkful in, smiling, about to blow chunks.

*

“Pleasure is our first and kindred good,” Epicurus, the ancient Greek philosopher, says in “Letter to Menoeceus.” “It is the starting point of every choice and of every aversion, and to it we come back, inasmuch as we make feeling the rule by which to judge of every good thing.” He details two anxiety-inducing beliefs that people live by, beliefs that can either soak life with joy or flood it with pain. The first: the gods will punish us for our bad behavior. The second: death is something to fear. But Epicurus thinks these beliefs are senseless, that the dark feelings they produce are self-generated, apparitions, fictions, rooted in nothing of the world. “Death is meaningless to the living because they are living,” he says, “and meaningless to the dead because they are dead.”

*

So what happens to pleasure when you are already dead, dead but still walking in the world of the living? What if you’ve been punished without understanding what it is you are being punished for? What if, for months on end, you are forced to get naked in a locked room, to touch and be touched? What if this braids and knots with your not knowing, and all the pleasure the world contains is whipped, whipped, whipped, and then hog-tied and carved into pain? What are you, Epicurus, if there is no place in the world for you? If you—just a child—have been ground down, finely powdered into nothing?

*

Pleasure is a fundamental part of mental life. Honey squeezed out of a plastic bear, Blow Pops, a perfectly ripened clementine—their sweetness gives pleasure, but the pleasure doesn’t come from the sensation of taste alone. Eight pieces of carrot cake or a tub of neon-pink Betty Crocker frosting can be sickening. The depth of pleasure comes from glossing the sensation, understanding the feeling through a lens. Limbic circuits—systems comprised of different regions of the brain—contextualize the sweetness so the single piece of cake is understood, both neurologically and psychologically, as pleasurable, while more is too much, maybe even terrible.

*

Still there were books, a tarnished enjoyment I took in the work of reading. From Where the Wild Things Are to Old Yeller and then The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, I lost myself in stories, and my fear and anxiety and sadness receded while I was immersed in another’s life. Reading satisfied my need to be alone while paradoxically, without my knowing it, connecting me to others.

*

By middle school I began to see the truth in the faces of the people around me. From the way my friends talked about how hungry they were for each other—how it felt to get it on, to touch and be touched—I started to realize that pleasure was indeed an amplitude of the world. An unattainable one for me. Pleasure was a secret room in the building of our lives, where my friends rollicked, where zippers were undone under the cover of darkness and blankets, where there was hot breath, moans. I was not invited into this room. Outside, I was cold, felt less than numb.

*

Anhedonia is the inability to experience pleasure in what is usually found pleasurable. So that loving touch—that body pressing into your own—doesn’t melt your insides. It burns. There is no after-workout glow, only a cinching decay. Friendships fill you with a stinging anxiety. Whatever is playing on the stereo—Bob Dylan, Ben Harper, Billie Holiday—is noxious. Your bones crave silence. Anhedonia is characteristic of many kinds of mental illness, including borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, and mood disorders.

*

Almost everyone—at one point or another—loses their way in middle school, and only fiction can keep them glued together when high school begins. So you tell yourself stories about who you are, about what happened. You were molested by a girl, not a young man, not your cousin, but you liked it because she was gorgeous, and you weren’t really molested because you wanted to do it, and anyway you liked it, liked it so so much. And to make sure no one around you sees what has been done, you decide to do what the world expects of you, promise that you will do it better than anyone else, that you will be a god. So there is more and more aggression and compulsion and violence. It doesn’t matter that you are dead—you are expected to be a man—and so you decide to do everything you can to make yourself real in the world. You swear that if you do it hard enough you feel something; it might not be pleasure, but it’s something. You get fucked up and fight and fuck and play sports and scream fuck and never tell anyone how you really feel and why don’t you ever tell anyone that you are sad or feel worthless? Because you are too busy kicking ass, or getting ass, or assuring someone that you are going to get fucked up this weekend, swearing, as you whip off your T-shirt and slap yourself in the face, that you’ll fuck up any motherfucker who wants to come get some.

*

“Pleasure is never as pleasant as we expect it to be and pain is always more painful,” Arthur Schopenhauer says. “The pain in the world always outweighs the pleasure. If you don’t believe it, compare the respective feelings of two animals, one of which is eating the other.” But what, Arthur, should we believe about the feelings of the animal trying to consume itself?

__________________________________

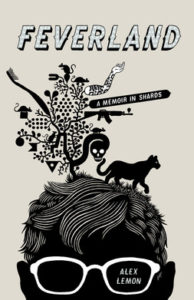

From “Things That Are: On Pleasure” from Feverland. Copyright © 2017 by Alex Lemon. Used with permission from Milkweed Editions.

Alex Lemon

Alex Lemon is a poet and the author of two works of nonfiction: Happy, selected by Kirkus as one of the best memoirs of 2010, and Feverland: A Memoir in Shards, forthcoming in 2017. His collections of poems include The Wish Book, Fancy Beasts, Hallelujah Blackout, and Mosquito; a fifth, Or Beauty, is also forthcoming. His writing has appeared in Esquire, River Teeth, Best American Poetry, AGNI, Bomb, Pleiades, and many other magazines and journals. He has received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Poetry, a Jerome Foundation Fellowship, and a Minnesota State Arts Board Grant, as well as the Paterson Award for Literary Excellence. He teaches in the low-residency MFA program at Ashland University and is Associate Professor at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, where he lives.