11 Novels That Thwart Traditional Narrative Structure (to Brilliant Effect)

Maria Adelmann Recommends Fiction That Creates Its Own Shapes

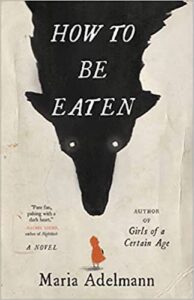

As a chronic short story writer and someone who reads novels with an almost hopeless disregard for plot, I was lost when I set out to write my own novel, How to Be Eaten, about classic fairy tale characters reimagined as modern women in group therapy for trauma.

I had begun the project as flash fiction. As a longer work, I imagined it would feature lots of tight and intense little pieces, little first-person snippets from each woman’s life, grounded in the premise of group therapy. I thought of myself as a quilter or collage artist, cutting out different pieces, laying them side-by-side, letting the reader see how they related to and played off each other.

The first draft was a disaster. It was less collage and more like the pieces for a collage, dumped on a table. Group therapy hadn’t magically grounded the story, as I had hoped it would, just created additional confetti. It was as if I was saying to the reader, “Here! You figure it out!”

I was stricken. What if the book I wanted to write could never contort itself into a novel? Did I need to consolidate voices by writing in the third person, rather than my beloved first? Did I need to put the women in a mental institution, so they could do plot-stuff together? Did I need to write a book I didn’t want to write? What, I kept thinking, did I need to concede?

Instead of starting a second draft, I started reading and re-reading novels that played with, thwarted, or totally disregarded traditional narrative structure. How did these books hang together?

All the books were grounded by something, of course—a theme, an organizational structure, a framework, a narrative thrust—but they also featured guideposts to help the reader on their way. No two books were the same; each author had a unique solution to not just accommodate but to elevate their particular task.

What I learned is this: A novel is not airline luggage, there are no strict rules, no arbitrary size and weight regulations that you must contemptuously squeeze your story into. You can create your own specifications to your advantage, but the story must still be deliverable—that is, comprehensible to the reader.

Here are ten novels that used their unconventional structures to brilliant effect.

*

George Saunders, Lincoln in the Bardo

A devastating novel about grief which revolves around the death of Abraham Lincoln’s son Willie shouldn’t be this hilarious, but it is set in a graveyard of chatty ghosts. Early chapters feature “found nonfiction,” that is, historical works spliced together, to set the scene for Willie’s death. But most of the novel is told in the first-person voices of ghosts who complain and reminisce. The book reads a little like a stage play, a technique that makes it very clear who is speaking at every moment—essential when there are over 150 narrators. Most of the novel takes place over the course of a single night, which helps contain it, and the ending features a climax that brings everyone together in a shared purpose.

Amy Tan, The Joy Luck Club

You could argue that The Joy Luck Club is really linked stories, as almost every beautifully crafted chapter can stand alone (and often does in short story anthologies), but the book features an overarching narrative and a clear organizational structure, which is helpfully laid out in the table of contents. The novel’s four sections are divided into four chapters (each with a different first-person narrator). The first section tells the stories of four Chinese immigrant mothers, the next of their American daughters, then the mothers again, then the daughters. Because one of the mothers has recently died, one daughter takes over her mother’s sections, and it’s her narrative that ultimately frames the book.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Novella? Novel? Anti-novel? It’s up for debate, but regardless, this slim work holds together as a unit because of its tight structure and thematic focus. It consists of 55 flash-fiction-type pieces, each describing a different city, along with conversations throughout that ground the book in its conceit, which is that Marco Polo is describing the cities to emperor Kubla Khan. There is a mathematical pattern to the book’s chapters, and Calvino himself likened the structure to a crystal, thinking of the chapters as part of a network rather than a linear series.

Patricia Lockwood, No One is Talking About This

No One is Talking About This uses the form of a novel in fragments to mimic short bursts of online interaction. What could feel gimmicky does not, thanks in part to the second half of the book, in which a tragedy puts the importance of being always online in sharp relief. Other fragmentary novels I love include Why Did I Ever? by Mary Robison and Dept of Speculation by Jenny Offill, both of which feature short, poetic snippets of text and have varying degrees of narrative thrust. On this, Jenny Offill said in an interview with The Paris Review:

“Fuck the plot, as Edna O’Brien said. What I try to capture as a writer is the feeling of being alive, of being awake. Because of this, I’m more apt to follow the wisp of a thought or a half-glimpsed image than chart a sequential series of events. But I absolutely believe in momentum. Momentum is not plot, but it has that same quality of urgency and forward motion, I think.”

Olga Tokarczuk, Flights

This cerebral novel about travel, movement, and liminal spaces features vignettes, prose-poemy meditations, and essay-like explorations. Though also fragmentary in form, the book has a distinctly different vibe than the novels above, in part because the fragments are much longer chapters (ranging from a half page to dozens of pages), and in part because this feels even less linear and more like a network of ideas. The novel’s themes are intricately connected to its structure, and the narrator often talks about both at the same time. Consider this paragraph about the narrator’s interest in strange curiosities:

“My set of symptoms revolves around my being drawn to all things spoiled, flawed, defective, broken. I’m interested in whatever shape this may take, mistakes in the making of the thing, dead ends. What was supposed to develop but for some reason didn’t; or vice versa, what outstretched the design. Anything that deviates from the norm, that is too small or too big, overgrown or incomplete, monstrous and disgusting. Shapes that don’t heed symmetry, that grow exponentially, brim over, bud, or on the contrary, that scale back to the single unit. I’m not interested in the patterns so scrutinized by statistics that everyone celebrates with a familiar, satisfied smile on their faces.”

William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying

A seemingly simple plot of a family transporting the dead matriarch of the family to be buried in her hometown is complicated and enriched by the 15 different narrators who tell the story. This particular kind of multi-voice novel, in which one subject or event is viewed from many different points of view, creates an effect like a cubist painting. Another example is the middle section of Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño, which features over 40 different narrators discussing the elusive founding duo of an arts movement. Similarly, the novella The Employees: A Workplace Novel of the 22nd Century by Olga Ravn features a series of employee interviews, which come together to create a broader narrative about a workplace in the future.

Bernardine Evaristo, Girl, Woman, Other

One of the unifying themes for this novel is identity, as (almost) all of the 12 main characters are Black, British women. Divided into five sections and an epilogue, the first four sections each include three chapters focusing on three different women whose lives are intertwined or connected in some way, often loosely. The novel is written in a poetry/prose form, featuring long lines and little end punctuation. A feeling of cohesiveness is created not just by unity of theme and style, but also by a fifth chapter that brings many of the women together at the after-party of a play created by the book’s first character.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire

Pale Fire takes the form of a 999-line poem and its commentary—including a forward, annotations, and index, written by the poet’s neighbor, a fellow academic that seems increasingly unhinged. You can read the book straight through, but it is fun to refer to the poem and various references as you go, as if you really have picked up this book and are surprised by what’s inside. Despite the unique conceit, the narrative that unfolds is fairly traditional in structure, providing a clear thread for the reader to follow through the unconventional form.

Rachel Cusk, Outline

The novel takes place in Athens, where the newly divorced narrator is teaching a creative writing class. In each of the book’s eight chapters, she meets a different person, and the chapter itself is mainly conversation that strays into monologue, with the narrator acting as an intently listening vessel, almost disappearing into other people’s stories. In an interview with The Guardian, Cusk explained her project, describing how she experienced the world after she was unmoored by her divorce:

“You are chucked out of the house, on the street, not defended any more, not a member of anything, you have no history, no network. What you have is people, strangers in the street, and the only way you can know them is by what they say. I became attuned to these encounters because I had no frame or context anymore. I could hear a purity of narrative in the way people described their lives. The intense experience of hearing this became the framework of the novel.”

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time,” begins this sci-fi book about the bombing of Dresden, which also features a semi-autobiographical first chapter. Plenty of traditional novels use flash-forwards and flashbacks, but in Slaughterhouse-Five you don’t know what is forward and what is back. The structure itself is commented on throughout, especially by the Tralfamadorians, an alien species who experience time all at once and read books the same way: “There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What we love in our books are the depths of many marvelous moments seen all at one time.” Though in the case of Billy Pilgrim, the moments are mostly not so marvelous.

___________________________________

Maria Adelmann’s How to Be Eaten is available now via Little, Brown.

Maria Adelmann

Maria Adelmann's work has been published by Tin House, n+1, The Threepenny Review, Indiana Review, Epoch, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, and others. She has received fellowships from Cornell University and The University of Virginia, where she earned her BA and MFA respectively. Maria has had quite a few jobs (visual merchandiser, instructor, hotel reviewer) in quite a few cities (New York, Baltimore, Copenhagen) and once on a ship. She enjoys learning new crafts and letting personal projects take over her life. You can visit her online at mariaink.com or on Twitter and Instagram @ink176.