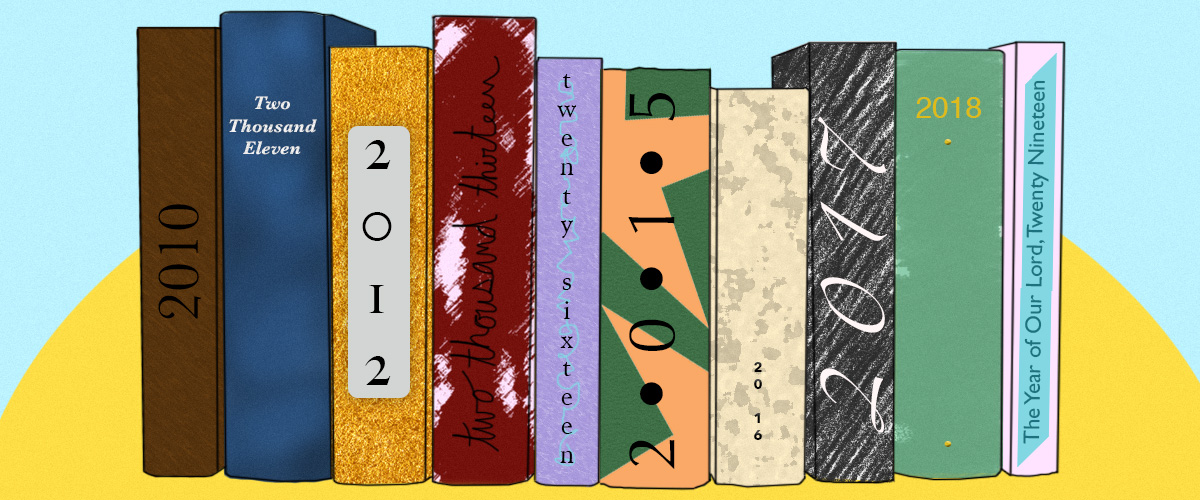

100 Books That Defined the Decade

For good, for bad, for ugly.

This is not a list of the best books of the decade. (This is, if you’re interested.) This is a list of books that, whether bad or good, were in one way or another defining for the last decade in American culture. (A global list would be nearly impossible, for obvious reasons. Accordingly, I’ve hewed to English-language and/or US publication dates, when relevant.) This is a list for general readers and followers of literary culture; it includes both major bestsellers and literary standouts, books that have become pop culture phenomenons, and books whose influence has been quieter and/or localized in literary circles. Obviously, it would not suffice for specialist purposes—I imagine a scientist would have selected a very different list of 100 books. (Or 100 books give or take: on a case by case basis, I have counted series as single books, or let the first book in a series stand in for the whole.)

Some of you may wonder if there’s been enough time and/or distance to really evaluate the last ten years in literature, or in culture for that matter. And the answer is probably . . . no! Or at least, our assessment of the last decade will certainly continue to change and harden as time goes on (if in fact it does—let’s cross our fingers and also vote). But even if hindsight is 20/20, there’s something to be said for a contemporary assessment, an in-miasma reading, if you will. So to that end, here are the 100 books that the members of the Literary Hub staff consider to be the most defining, important, transformative, and/or illustrative of the decade that was.

*

Jonathan Franzen, Freedom (2010)

There is, after all, a kind of happiness in unhappiness, if it’s the right unhappiness.

*

Essential stats: Franzen’s follow up to The Corrections was a #1 bestseller; sold almost 100,000 copies before Oprah called it a masterpiece and picked it for her book club; won the John Gardner fiction prize and was a finalist for the LA Times book prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

What did the critics say? They were torn. Here’s Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times:

Jonathan Franzen’s galvanic new novel, Freedom, showcases his impressive literary toolkit—every essential storytelling skill, plus plenty of bells and whistles—and his ability to throw open a big, Updikean picture window on American middle-class life. With this book, he’s not only created an unforgettable family, he’s also completed his own transformation from a sharp-elbowed, apocalyptic satirist focused on sending up the socio-economic-political plight of this country into a kind of 19th-century realist concerned with the public and private lives of his characters.

But here’s Ron Charles in The Washington Post:

So what is it about Jonathan Franzen and poo? In 2001, his wonderful breakthrough novel, The Corrections, was momentarily stunk up by a scene in which a senile old man imagines his feces talking back to him. A decade later, Franzen’s more staid, more mature, but all around less exciting Freedom reaches its comic zenith when a young man searches through his own excrement with a fork. What seemed like a sophomoric indulgence in that earlier tour de force now smells stale.

Behind the title: “But since we’re all friends here,” Franzen once explained, “I will mention that I think the reason I slapped the word on the book proposal I sold three years ago without any clear idea of what kind of book it was going to be is that I wanted to write a book that would free me in some way.

And I will say this about the abstract concept of ‘freedom’; it’s possible you are freer if you accept what you are and just get on with being the person you are, than if you maintain this kind of uncommitted I’m free-to-be-this, free-to-be-that, faux freedom.”

But is it a Great American Novel? If you believe TIME, then yes.

And to be perfectly fair, I took this book everywhere until I finished it: bars, birthday parties. But, yo J Franz, I’m really happy for you, and I’mma let you finish, but Jennifer Egan had one of the best novels of all time this year. One of the best novels of all time!

Franzen on Oprah:

Extra credit: Jonathan Franzen’s 10 Rules for Novelists · Jonathan Franzen on Alice Munro’s Runaway · Jonathan Franzen in conversation with Wyatt Mason

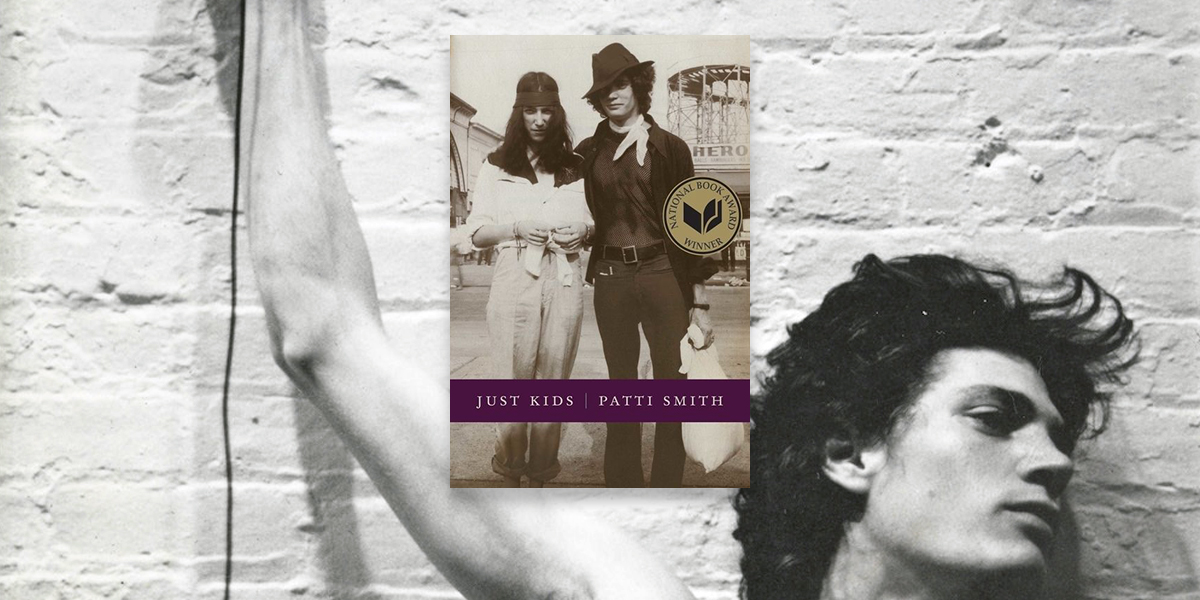

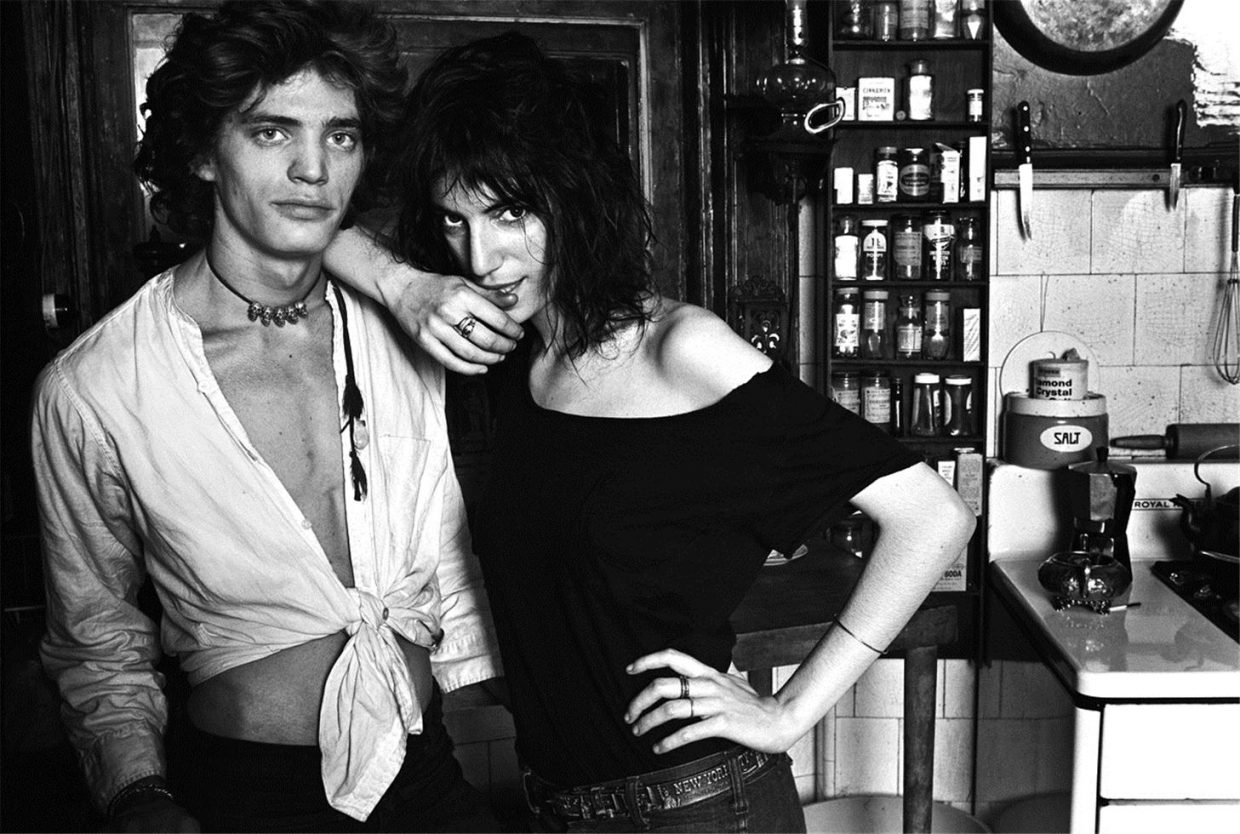

Patti Smith, Just Kids (2010)

Where does it all lead? What will become of us? These were our young questions, and young answers were revealed. It leads to each other. We become ourselves.

*

Essential Stats: This memoir from beloved singer-songwriter, poet, and high priestess of New York punk—which detailed her complicated relationship with the experimental artist Robert Mapplethorpe—won the 2010 National Book Award for Nonfiction, made more end-of-year Best Of lists than you can shake a stick at, and was even crowned the One Book One New York winner earlier this year.

Did the critics like it? You bet they did. Tom Carson, writing in the New York Times, called it “the most spellbinding and diverting portrait of funky-but-chic New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s that any alumnus has committed to print”; Entertainment Weekly’s Leah Greenblatt dubbed it “a poignant requiem…and a radiant celebration of life”; and Kirkus labeled it “riveting and exquisitely crafted.”

Why did it strike such a chord with readers? Because who wouldn’t want to traverse the grimy and glorious world of the 1970s NYC art and music scene with Smith as their guide?

Because the Night: belongs to lovers . . .

Patti Smith reading from Just Kids and performing “Because the Night”:

–DS

Jennifer Egan, A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010)

I don’t want to fade away, I want to flame away—I want my death to be an attraction, a spectacle, a mystery. A work of art.

*

Essential Stats: A post-postmodern tale of music and memory, continuity and disconnection, told in thirteen interrelated stories (one of which takes the form of a Power Point presentation), inspired in equal measure by Proust and The Sopranos, which bagged both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

So is it a novel or a collection of short stories? Both. Neither. It doesn’t matter. Why must we put labels on everything?

What did the Pulitzer Prize Board have to say about it? They called it “an inventive investigation of growing up and growing old in the digital age, displaying a big-hearted curiosity about cultural change at warp speed”

Did I hear that the folks at HBO were turning it into a TV show? You did, and they were, but the proposal has since been dropped [sigh], so for now you’ll have to make do with this dream casting.

Here’s Egan reading the first chapter of the novel:

–DS

Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (2010)

The art of medicine is long, Hippocrates tells us, “and life is short; opportunity fleeting; the experiment perilous; judgment flawed.”

*

Essential stats: Mukherjee’s groundbreaking work of history and science ran a cool 592 pages; it won the 2011 Pulitzer in General Nonfiction, the Guardian first book award, the inaugural PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award, and was a New York Times bestseller.

What’s a “biography” of cancer, anyway? In this riveting and influential book, Mukherjee traces the known history of our most feared ailment, from its earliest appearances over five thousand years ago to the wars still being waged by contemporary doctors, and all the confusion, success stories, and failures in between.

Genius power couple: Siddhartha Mukherjee and Sarah Sze.

The Pulitzer committee’s summary: “An elegant inquiry, at once clinical and personal, into the long history of an insidious disease that, despite treatment breakthroughs, still bedevils medical science.”

They even made it into a TV show:

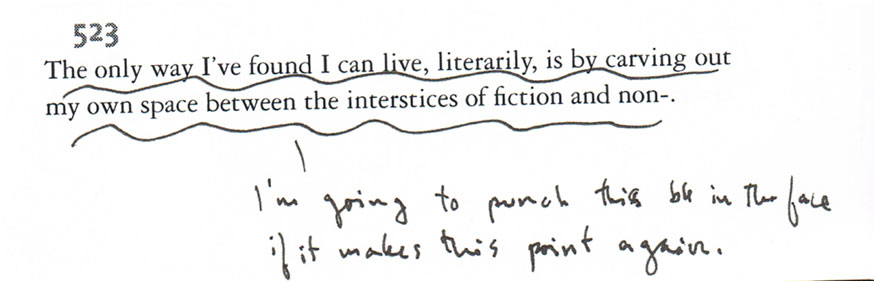

David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (2010)

The novel is dead. Long live the anti-novel, built from scraps.

*

Essential stats: 618 numbered sections, 26 chapters, including “hundreds of quotations that go unacknowledged in the body of the text.” These are acknowledged only at the end of the book, in the 15-page appendix, at the behest of Random House’s lawyers, though Shields begs the reader to cut this out with “a sharp pair of scissors or a razor blade or box cutter” or at the very least not to read them. Oh and also, innumerable think pieces and counter-arguments and exhausting discourse of varying levels of intensity and intelligence.

What was it all about? Basically that remix culture, collage, plagiarism, intertextuality, and genre-blending (especially between fictional and nonfictional forms) and was our generation’s way of seeking a sense of “reality” in art. Or as Shields himself put it in the beginning of this book:

My intent is to write the ars poetica for a burgeoning group of interrelated (but unconnected) artists in a multitude of forms and media (lyric essay, prose poem, collage novel, visual art, film, television, radio, performance art, rap, stand-up comedy, graffiti) who are breaking larger and larger chunks of “reality” into their work. (Reality, as Nabokov never got tired of reminding us, is the one work that is meaningless without quotation marks.)

What did the critics say? Some appreciated it, others not so much.

In the New York Times Book Review, Luc Sante was open to Shield’s vision:

On the whole . . . he is a benevolent and broad-minded revolutionary, urging a hundred flowers to bloom, toppling only the outmoded and corrupt institutions. His book may not presage sweeping changes in the immediate future, but it probably heralds what will be the dominant modes in years and decades to come. The essay will come into its own and cease being viewed as the stepchild of literature. Some version of the novel will endure as long as gossip and daydreaming do, but maybe it will become more aerated and less controlling. There will be a lot more creative use of uncertainty, of cognitive dissonance, of messiness and self-consciousness and high-spirited looting. And reality will be ever more necessary and harder to come by.

In The Guardian, Blake Morrison wrote:

Shields sells fiction short. “Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole,” he claims. Does it? Isn’t this patronising to novelist and reader alike? Can’t wresting order out of chaos be a triumph against the odds? And what exactly is this hated creature, the “conventional” or “standard” novel? The premise is that because life is fragmentary, art must be. But poems that rhyme needn’t be a copout. And novels with a clear plot and definite resolution can still be full of ambiguity, darkness and doubt. By the same token, to engage with the dilemmas of an imaginary character means learning to empathise with otherness, and few skills are more important in the world today.

Shields has written a provocative and entertaining manifesto. But in his hunger for reality, he forgets that fiction also offers the sustenance of truth.

In The New Yorker, James Wood was mostly unimpressed.

Shields prosecutes an effective, if coarse, sub-Barthesian argument against the traditional novelistic machinery. He rants a bit, apparently fearful that if he were quieter we would not believe in his sincerity; hungry for his own reality, certainly, he also mentions himself a great deal . . . Like most aesthetic manifestos, his book is an argument for realism; it’s just that he prefers his kind of realism to that of traditional fiction, which strikes him as fake.

. . .

His complaints about the tediousness and terminality of current fictional convention are well-taken: it is always a good time to shred formulas. But the other half of his manifesto, his unexamined promotion of what he insists on calling “reality” over fiction, is highly problematic. A moment’s reflection might prompt the thought, for example, that Tolstoy (who so often reproduced reality directly from life) is the great “reality-artist,” and a powerful argument against Shields’s anti-novelistic religious fury. When one first reads Tolstoy, one feels the bindings being loosed, and the joyful realization is that the novel is stronger without the usual nineteenth-century appurtenances—coincidence, eavesdropping, melodramatic reversals, kindly benefactors, cruel wills, and so on. It is hard to imagine a writer more obviously “about what he’s about.” Strangely enough, using Shields’s aesthetic terms and most of his preferred writers (along with some of those he seems not to prefer), a passionate defense of fiction and fiction-making could easily be made. Perhaps he will write that book next.

And then there’s Sam Anderson:

And seven years later, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Stephen Marche argued that the novel was only published before its time:

“The lifespan of a fact is shrinking,” Shields wrote in 2010. “I don’t think there’s time to save it.” Time for the fact officially ran out on November 9, 2016, leaving us faced with numbing and confounding questions that Reality Hunger posed early and urgently: How do we find the truth in an age when technology and politics have rendered the line between fiction and nonfiction nearly impossible to distinguish? How do we write about the real world when reality itself is up for grabs? Reality Hunger has become, quite unintentionally to its author, a book about how to write now, in 2017.

That’s still up for debate.

Piper Kerman, Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women’s Prison (2010)

Two hundred women, no phones, no washing machines, no hair dryers—it was like Lord of the Flies on estrogen.

*

Essential stats: The most important stat about “nice blond lady” Kerman’s extremely buzzy memoir of her time in a women’s federal prison is, of course, that it was adapted into the long running television show (2013-2019) of the same name, which in the New York Time’s look back at the decade in culture, Wesley Morris called “the best show on TV, in any format.” It was Netflix’s most watched original series this decade. In fact, many reviewers concluded that the show was much better than its source material—but then again, the show had a lot more time.

What did the critics say? Opinions were mixed. In Slate, Jessica Grose wrote:

If you pick up Kerman’s book looking for a realistic peek inside an American prison, you will be disappointed. Orange Is the New Black belongs in a different category, the middle-class-transgression genre. . . . The tales of these well-educated women follow essentially the same narrative arc: Girl is bored, girl seeks titillating transgression, girl regrets, girl renounces prior misdeeds, girl lives happily ever after. The girl never serves out a life sentence carving deadly points on toothbrushes or ends up a strung-out old lady on a street corner.

J. Courtney Sullivan was somewhat gentler in the Chicago Tribune, calling it “a perceptive, if imperfect inside look at our criminal justice system and the women who cycle through it.”

Ok, so the real import of the book is the show. What made that so good? As TIME’s TV critic Judy Berman wrote, Orange Is the New Black is the most important television show of the decade because not only was it good, but it smashed all the molds around it:

When it came to representation, this wasn’t merely the first prestige show since The Wire built around poor and nonwhite people—or the rare program intended for a general audience that featured more than a token queer regular. It also endowed each of these characters with stereotype-defying specificity. In 2014, when this magazine declared that America had reached a “transgender tipping point,” Laverne Cox’s breakthrough role as trans inmate Sophia Burset made her the face of that moment. For once, women whom mainstream society habitually ignored were being represented in pop culture as individuals with virtues and flaws, rather than as a monolithic mass of degenerates or vixens.

The show’s mix of gallows humor and high tragedy disrupted genre categories to the extent that the Emmys moved it from comedy to drama between Seasons 1 and 2. And over the years, its unflinching depiction of the American justice system has both mirrored and catalyzed intensifying debates around mass incarceration, private prisons, systemic racism, economic inequality and police violence against people of color. Some of these story lines have been controversial: Kohan got blowback for having a guard kill Samira Wiley’s bighearted Poussey Washington at the end of Season 4. Maybe the point was that even Litchfield’s gentlest inmate could be a casualty of police brutality, but many fans just saw another black body sacrificed in service of a plot twist. Still, the conversations that have come out of Orange’s perceived missteps have felt as vital as the ones around its successes.

Michael Lewis, The Big Short (2010)

What are the odds that people will make smart decisions about money if they don’t need to make smart decisions—if they can get rich making dumb decisions? The incentives on Wall Street were all wrong; they’re still all wrong.

*

Essential stats: This is really a book about the 2000s, of course, and what happened to the United States Housing bubble, and all of our credit, but as part of this decade has been defined by all the reeling that happened after the 2008 financial crisis, I think a book that unpacks it should count. Readers agreed; it spent 28 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. It also was awarded the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights Book Award.

What did the critics say? They loved it. “The Big Short is not half the fun of Liar’s Poker, but it is more important,” wrote James Buchan in The Guardian. “Lewis, who lives in Paris, is too worldly to make his parade of short misfits and fantasists into American heroes. In one of those moments of self-knowledge that strike even financiers, Eisman understands that he was shorting not Wall Street but humanity itself. . . The American public has not yet grasped the nature and extent of this crime—but it will, it will.”

And of course, there’s the movie: which may have actually done more to explain what happened to people than the book (or maybe not, it was slightly confusing, and how is Batman involved, and will anyone ever let Jeremy Strong out of that same corporate conference room), and which won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay:

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow (2010)

The nature of the criminal justice system has changed. It is no longer primarily concerned with the prevention and punishment of crime, but rather with the management and control of the dispossessed.

*

Essential stats: In this groundbreaking book, civil rights litigator and legal scholar Alexander argues, essentially, that mass incarceration is our generation’s version of Jim Crow. The New Jim Crow won a slew of awards and critical praise; in The New York Review of Books, Darryl Pinckney wrote that “the literature on race and the criminal justice system is extensive; the film documentaries about the problem tell us things we need to know; the jails keep filling with black and brown people.

Now and then a book comes along that might in time touch the public and educate social commentators, policymakers, and politicians about a glaring wrong that we have been living with that we also somehow don’t know how to face. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander is such a work.

What was its impact? Take it from our own Olivia Rutigliano, who wrote:

I read Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow when it first came out, and I remember its colossal impact so clearly—not just on the academic world (it is, technically, an academic book, and Alexander is an academic) but everywhere. It was published during the Obama Administration, an interval which many (white people) thought signaled a new dawn of race relations in America—of a kind of fantastic post-racialism. Though it’s hard to look back on this particular zeitgeist now (when, and I still can’t believe I’m writing this, Donald Trump is president of the United States) without decrying the ignorance and naiveté of this mindset, Alexander’s book called out this the insistence on a phenomenon of “colorblindness” in 2012, as a veneer, as a sham, or as, simply, another form of ignorance. “We have not ended racial caste in America,” she declares, “we have merely redesigned it.” Alexander’s meticulous research concerns the mass incarceration of black men principally through the War on Drugs, Alexander explains how the United States government itself (the justice system) carries out a significant racist pattern of injustice—which not only literally subordinates black men by jailing them, but also then removes them of their rights and turns them into second class citizens after the fact. Former convicts, she learns through working with the ACLU, will face discrimination (discrimination that is supported and justified by society) which includes restrictions from voting rights, juries, food stamps, public housing, student loans—and job opportunities. “Unlike in Jim Crow days, there were no ‘Whites Only’ signs.” Alexander explains. “This system is out of sight, out of mind.” Her book, which exposes this subtler but still horrible new mode of social control, is an essential, groundbreaking achievement which does more than call out the hypocrisy of our infrastructure, but provide it with obvious steps to change.

Here’s Alexander delivering a lecture at the University of Chicago in 2013:

Suzanne Collins, Mockingjay (2010)

It takes ten times as long to put yourself back together as it does to fall apart.

*

Essential stats: It sold 450,000 copies in the first week, and millions of copies since. And it was made into a movie, of course—nope, two major blockbusters, 2014’s The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 and 2015’s The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1. I regret to tell you that while the Hunger Games movies are in general pretty good, these two are not at the top of the list.

Wait, which one was Mockingjay? Okay, yes, it was the third one. The Hunger Games, the book that introduced us all to Katniss Everdeen, was published in 2008, and its sequel, Catching Fire, was published in 2009. But since all four (4) of the movies came out in the last decade, I thought the trilogy/franchise/really genius idea deserved a mention.

Is it any good? Yes. I enjoyed the Hunger Games series in general, but I also appreciated this novel in particular. Unlike so many fantasy series and epic stories, in this book, Collins recognizes that her protagonist would be . . . well, pretty fucked up after everything she went through. And she’s not afraid to show it, and let her fail, and have PTSD. I mean, we all would, it’s just that it doesn’t exactly make for neat heroism, and so many writers and filmmakers ignore it. Anecdotally, it seems that Collins’s treatment of Katniss has started a shift towards emotional verisimilitude in characters like these, which may itself be a major defining moment of the decade.

Also, the series, and someone named PistolShrimps, gave us this, which I personally think about once a week (consider my decade defined):

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)

She’s the most important person in the world and her family living in poverty. If our mother is so important to science, why can’t we get health insurance?

*

Essential stats: Skloot’s groundbreaking work of history and science won the 2011 National Academies Communication Award, which recognized “excellence in reporting and communicating science, engineering, and medicine to the general public,” as well as the Heartland Prize, the Wellcome Trust Book Prize, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Young Adult Science Book Award. The paperback spent 75 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, and it is still widely taught in schools.

What made it defining? This book, which uncovered the story of an unknown woman whose cells—harvested without her permission or knowledge—became vital to medicine and science (in terms of developing the polio vaccine, for cloning, for gene mapping, etc.) was one of the first—if not the first—to tackle questions of how issues of race and class affected medical research for a general audience. It’s also the moving story of the Lacks family, who worked with Skloot on this book.

Plus, Oprah Winfrey and Rose Byrne starred in the movie:

Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá, Sex at Dawn (2010)

The campaign to obscure the true nature of our species’ sexuality leaves half our marriages collapsing under an unstoppable tide of swirling sexual frustration, libido-killing boredom, impulsive betrayal, dysfunction, confusion, and shame.

*

Essential stats: Sex at Dawn spent three weeks on The New York Times best-seller list, starting at #24, and won the Ira and Harriet Reiss Theory Award in 2011.

Let’s get right to the drama. This book was incredibly divisive. Dan Savage loved it, calling it “the single most important book about human sexuality” since Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. It was Peter Sagal of NPR’s favorite book of 2010. It received a lot of criticism from the academic world.

Why was it controversial? It argued, basically, that monogamy is not the natural state of human sexuality. Authors Ryan and Jethá defied conventional wisdom around the development of human sexuality by writing that human beings did not evolve to be monogamous. They drew on research from anthropology, primatology, and other fields to argue that the monogamous nuclear family structure was created for economic reasons after the rise of agrarian life, but that system did nothing to change human beings’ naturally promiscuous instincts, and misunderstanding those instincts has led to misinformation and unhappiness in modern life, also a lot of divorce. Unsurprisingly, this caused a bit of a stir!

Some anthropologists had explored similar ideas before, but Sex at Dawn’s extensive argument, coupled with a writing style geared toward a general audience, brought this conversation to many people for the first time.

How did the authors respond? In a piece for Psychology Today, Ryan wrote that critics who were getting worked up were “talking about themselves, often quite revealingly, at that.” Turns out people have a lot of feelings about monogamy.

So… should we all be polyamorous? Ryan told Salon in 2010 that “We’re not really arguing for any particular arrangement. We don’t even really know what to do with this information ourselves. What we’re trying to do in the book is give people a more accurate sense of where we came from, why we are the way we are, and why certain aspects of life feel like a bad fit. I think a lot of people make a commitment when they’re in love, which is a sort of a delusional state that lasts a couple of years at most. I think it was Goethe who said that love is an unreal thing, and marriage is a real thing, and any confusion of the real with the unreal always leads to disaster.” Great.

Ryan’s TED Talk:

–CS

Tana French, The Dublin Murder Squad Series (2010-2016)

Trust your instincts, Dad always says. If something feels dodgy to you, if someone feels dodgy, you go with dodgy. Don’t give the benefit of the doubt because you want to be a nice person, don’t wait and see in case you look stupid. Safe comes first. Second could be too late.

*

Essential stats: To be fair, Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series started in 2007, with the publication of her debut, In the Woods. It was followed by The Likeness (2008), Faithful Place (2010), Broken Harbor (2012), The Secret Place (2014), and The Trespasser (2016). (Her most recent novel, The Witch Elm, is a standalone.) So I’m counting the series as a whole, as it’s been primarily in this decade, despite the fact that my favorite of the books, The Likeness (obviously), is just shy of it. Most of her awards came for In the Woods, but Broken Harbor won the Los Angeles Book Prize and the Irish Crime Fiction Award. And the adaptation of the series has recently debuted on Starz.

Why were these so defining? Tana French has been a major crossover writer between the crime and literary genres; she also inspires fervent fandom. As Laura Miller wrote in The New Yorker:

French’s readers like to go online and rank the books . . . in order of preference, and while there’s no consensus, it’s taken for granted that anybody who’s read one will very shortly have read them all. The early copy of The Trespasser that I presented as a hostess gift this summer was greeted with ecstasy. The recipient spent much of the weekend shuffling around in a robe with the book clutched to her chest and a distracted expression on her face. Most crime fiction is diverting; French’s is consuming. A bit of the spell it casts can be attributed to the genre’s usual devices—the tempting conundrum, the red herrings, the slices of low and high life—but French is also hunting bigger game. In her books, the search for the killer becomes entangled with a search for self. In most crime fiction, the central mystery is: Who is the murderer? In French’s novels, it’s: Who is the detective?

Part of this is down to French’s unusual format. Unlike traditional series, each book has a different protagonist—usually one of the more minor characters from the book preceding it, which means that not only can each book be read as a standalone, but French can do a lot of emotional damage to her detectives (and ask the above question), without running into the whole Harry Potter in book five issue. The series is also, not for nothing, perfect for “binge reading,” which is apparently a thing these days.

Here’s the very atmospheric trailer for the adaptation:

E. L. James, Fifty Shades of Grey (2011)

“Why don’t you like to be touched?”

“Because I’m fifty shades of fucked-up, Anastasia.”

*

Essential stats: Clocking in at a hefty 514 pages, this novel famously began as Twilight fan-fiction and then became the fastest-selling paperback in UK history. It vaulted James to the top of Forbes’s list of highest-earning authors in 2013 with a reported income of $95 million, was translated into 52 languages, and sold over 125 million copies worldwide (as of 2015).

Essential stats according to this industrious Amazon reviewer: “I have discovered that Ana says “Jeez” 81 times and “oh my” 72 times. She “blushes” or “flushes” 125 times, including 13 that are “scarlet,” 6 that are “crimson,” and one that is “stars and stripes red.” (I can’t even imagine.) Ana “peeks up” at Christian 13 times, and there are 9 references to Christian’s “hooded eyes” and 7 to his “long index finger.” Characters “murmur” 199 times and “whisper” 195 times (doesn’t anyone just talk?), “clamber” on/in/out of things 21 times, and “smirk” 34 times. Finally, in a remarkable bit of symmetry, our hero and heroine exchange 124 “grins” and 124 “frowns”… which, by the way, seems an awful lot of frowning for a woman who experiences “intense,” “body-shattering,” “delicious,” “violent,” “all-consuming,” “turbulent,” “agonizing” and “exhausting” orgasms on just about every page.”

Why the necktie? Oh:

And yet, the novel increased sales not of silk neckties, but of “soft cotton rope.”

What do the critics say? Mostly some shade of “ugh.” But Alessandra Stanley put it rather more elegantly in The New York Times, writing “Fifty Shades of Grey is to publishing what Spanx was to the undergarment business: an antiquated product re-imagined as innovation. . . . As female fantasies go, it’s a twofer: lasting love and a winning Mega Millions lottery ticket. And what is shameful about Fifty Shades of Grey isn’t the submissive sex, it’s the Cinderella story.”

Did your mom read it? No, my mom prefers Virginia Woolf.

Though to be fair, everyone’s mom likes this sort of thing:

George R. R. Martin, A Dance with Dragons (2011)

Kill the boy, Jon Snow. Winter is almost upon us. Kill the boy and let the man be born.

*

Essential stats: I mean, it’s . . . Game of Thrones? A Dance with Dragons, like all of the rest of the books, was a huge bestseller, and runs 1,040 pages and almost 415,000 words. In total, the books have sold more than 90 million copies worldwide, and been translated into almost 50 languages (last time anyone checked). And that’s with only 5 of a planned 7 novels completed and published, a fact which causes some fans feelings ranging from anxiety to extreme annoyance.

Why was it so important? The only one of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books that was published this decade is the most recent one, A Dance with Dragons, way back in 2011 (A Dance with Dragons = season 5). But there’s no denying that this series has been one of the biggest cultural phenomenons of the decade, if not the biggest, due primarily to the HBO adaptation that ran from 2011 to 2019. That’s almost wall-to-wall cultural relevance. It was absolutely the most discussed television show of the decade, and has been credited with popularizing the genre of fantasy for general consumers (or maybe just making budgets for fantasy television projects balloon). You could (and can) buy every type of related merch, even your own six foot Iron Throne. (Why??) It even inspired Taylor Swift’s latest album.

But wait, isn’t it all about rape and violence and gratuitous female nudity and that one white savior lady? Well, yes. What country do you think you live in? But yeah, though I read and enjoyed the books, I had to stop watching the show at a certain point. Just not worth it. Dragons are very cool, though. Who wants to play D&D later?

Actually, it’s pretty much just a ludicrous soap opera:

And how about that ending?

Hey, who’s better, George R. R. Martin or J. R. R. Tolkien? You’ll just have to decide for yourself:

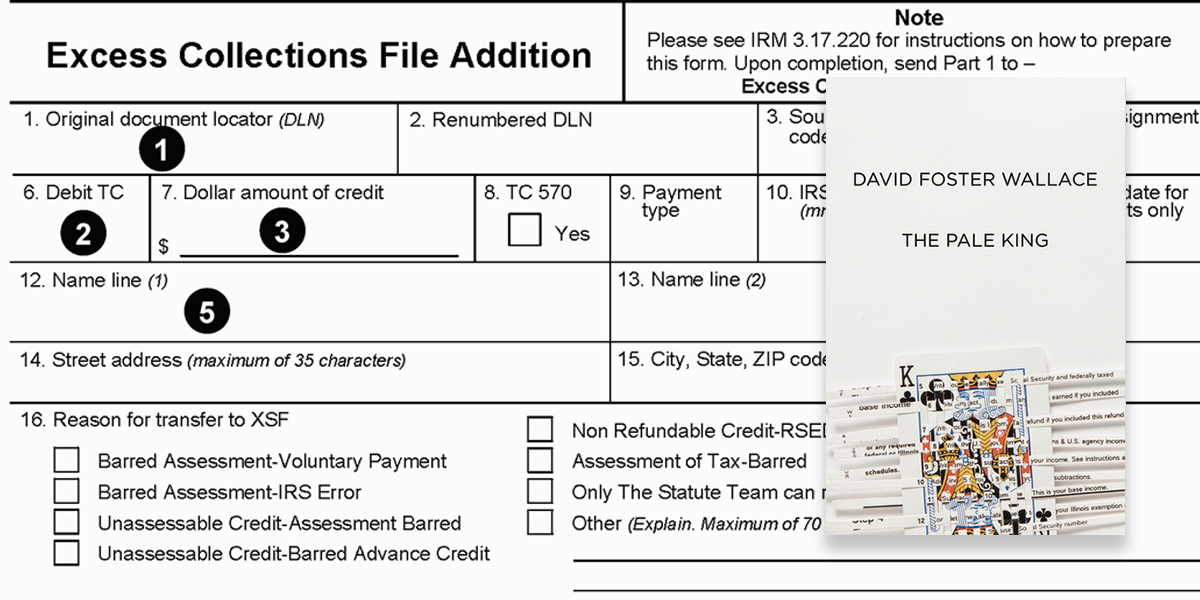

David Foster Wallace, The Pale King (2011)

How odd I can have all this inside me and to you it’s just words.

*

Essential Stats: Wallace’s unfinished opus of “loneliness, depression and the ennui that is human life’s agonized bedrock” was a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize and the talk of the book world in the Spring of 2011. Coming in at 548 pages (brief, by Infinite Jest standards), it consists of 50 relatively standalone chapters, many of which focus on the experiences of a handful of employees of the IRS in Peoria, Illinois in 1985.

Wait a second…didn’t David Foster Wallace die in 2008? No flies on you. Indeed he did die, but before his suicide Wallace organized the unfinished manuscript chapters of his third novel in such a way that they could be found by his widow Karen Green, and edited into coherence by his friend and editor Michael Pietsch.

So…is it any good? Well, that depends on who you ask. Most reviewers seemed awed and frustrated in equal measure. The New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani called it “breathtakingly brilliant and stupefying dull—funny, maddening and elegiac.” Jonathan Raban, in his mixed New York Review of Books assessment, wrote: The best one can do is to imagine The Pale King as half a book, at most, and believe its author to have been capable of pulling off the miracle in its unwritten pages—which isn’t inconceivable.” The consensus seems to be that The Pale King is an exhausting, but ultimately worthy, undertaking for DFW stans.

Well, that’s a relief. So his reputation remains unblemished? Em . . . sort of . . . I guess. . . mostly. . .

Perhaps you would like to see some monologues from The Pale King by famos:

–DS

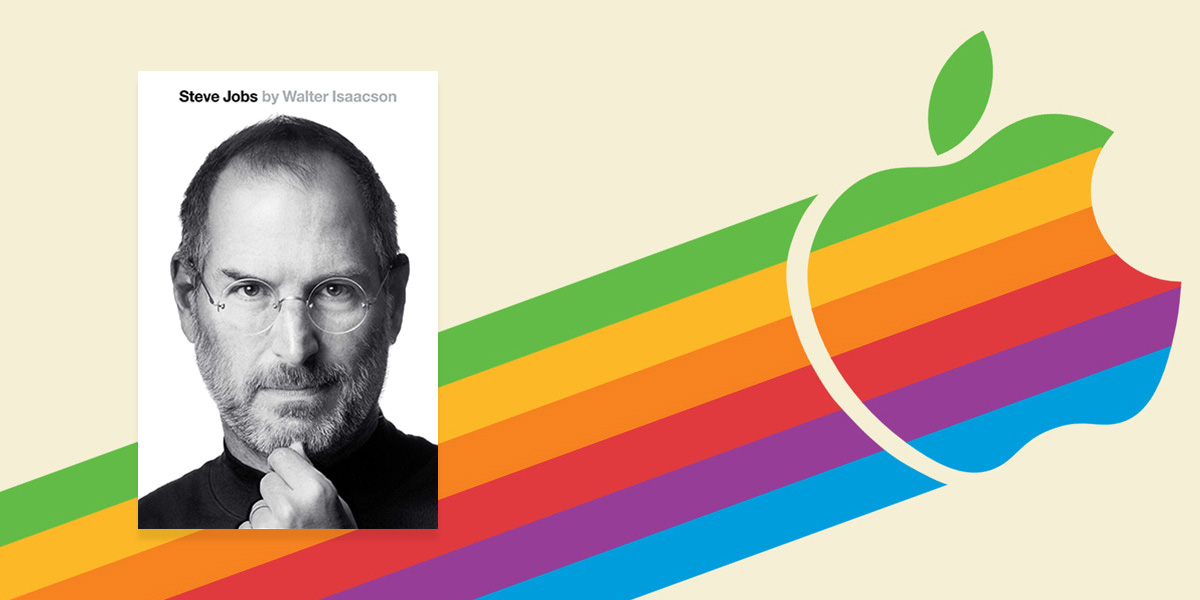

Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (2011)

One way to remember who you are is to remember who your heroes are.

*

Essential stats: Isaacson’s landmark biography of Steve Jobs—who, not for nothing, has had a major hand in defining this decade for all of us, for good or ill (spoiler: ill)—was published in October 2011, just 19 days after Jobs’ death. By December, it was already Amazon’s best-selling book of the year. Obviously, it was immediately turned into a film, written by Aaron Sorkin, directed by Danny Boyle, and starring Michael Fassbender as Jobs.

Why was it defining? The cover alone is iconic—and it’s the only part of the book Jobs asked for oversight on. (It’s from a 2006 Fortune magazine photoshoot, and was shot by Albert Watson on film.) But it also marked the end of an era, especially for those who had grown up while Jobs was a world-changing superstar, and worshipped him (my father has a literal book called Are you a Mac Person or a PC Weenie?). And more importantly, as Janet Maslin writes in The New York Times,

Mr. Isaacson treats Steve Jobs as the biography of record, which means that it is a strange book to read so soon after its subject’s death. Some of it is an essential Silicon Valley chronicle, compiling stories well known to tech aficionados but interesting to a broad audience. Some of it is already quaint. . . . And some is definitely intended for future generations.

Can I help myself? No, I’m afraid I am a huge dork, sorry not sorry.

Téa Obreht, The Tiger’s Wife (2011)

The dead are celebrated. The dead are loved. They give something to the living. Once you put something into the ground, Doctor, you always know where to find it.

*

Essential stats: Obhret’s debut novel was a finalist for the National Book Award, and the winner of the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2011—and oh right, she was 25 at the time, which made her the youngest writer ever to receive the latter honor. In 2010, Obreht was named as one of the New Yorker‘s 20 Under 40 and one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35. Also, the novel sold like hotcakes. You read it. Your friends read it. Your mom read it. Your mom’s friends read it. Look, American love a wunderkind (and sometimes they also love very good books).

What did the critics say? They were pretty much all about it. Michiko Kakutani called it “a hugely ambitious, audaciously written work that provides an indelible picture of life in an unnamed Balkan country still reeling from the fallout of civil war,” and Liesl Schillinger put her finger on the very thing that always so impresses me about Obreht’s writing, that it is “filled with astonishing immediacy and presence, fleshed out with detail that seems firsthand, The Tiger’s Wife is all the more remarkable for being the product not of observation but of imagination.”

Watch Obreht read a bit of the book:

Colson Whitehead, Zone One (2011)

New York City in life was much like New York City in death. It was still hard to get a cab, for example.

*

Essential stats: It was a New York Times bestseller, and much discussed in hushed terms for being a zombie novel written by a literary novelist—like, so crazy, right you guys, pass the Brie?

Why was it defining? This was a decade of genre-bending, and smashing, and dissolving, and while literature has always played with forms and mixed its pots, Whitehead’s literary zombie novel still felt boundary-pushing. Or as Dan Kois put it recently in Vulture:

In a century marked by the erosion of the high-low divide that once separated “literature” from genre fiction, Zone One is the exemplary hybrid, the paragon of what each mode offers the other. Whitehead’s post-apocalyptic experiment—a zombie novel that’s also a 9/11 meditation that’s also a cultural satire—delivers both moving psychological realism and satisfying gore. (The moment when hero Mark Spitz discovers his undead mother feasting on his dad’s corpse will stay with me until the day a zombie chows down on mine.) Whitehead has written terrific novels that more directly address the horrors of American history, but never one that more accurately portrays the horrors of the American present.

The fact that this seems pretty commonplace now (the genre-bending, not the undead mother feasting, it seems important to say) only goes to show the influence Zone One, and other works like, have had on our cultural appetites.

Stephen Greenblatt, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (2011)

The greatest obstacle to pleasure is not pain; it is delusion.

*

Essential stats: Historian Stephen Greenblatt’s book about the origin of modernity (in a text by Lucretius) won the 2011 National Book Award for Nonfiction and the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction, and provoked much discussion, especially among literary types charmed by the idea that a single book—a single poem!—could have catalyzed the Renaissance.

I remember when everyone was reading this. But didn’t it get debunked or something? Lots of critics loved it. But some, especially historians, noted a disturbing lack of academic rigor and discordance with contemporary scholarship about the Middle Ages in particular.

In his 2012 essay “Why Stephen Greenblatt is Wrong—and Why It Matters” in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Jim Hinch was blunt:

Simply put, The Swerve did not deserve the awards it received because it is filled with factual inaccuracies and founded upon a view of history not shared by serious scholars of the periods Greenblatt studies … The Swerve, in fact, is two books, one deserving of an award, the other not. The first book is an engaging literary detective story about an intrepid Florentine bibliophile named Poggio Braccionlini … brimming with vivid evocations of Renaissance papal court machinations and a fascinating exploration of Lucretius’s influence on luminaries ranging from Leonardo Da Vinci, to Galileo, to Thomas Jefferson, is wonderful. The second Swerve is an anti-religious polemic … Greenblatt’s caricatured Middle Ages might have passed muster with Enlightenment-era historians. Present-day scholarship, especially the findings of archeologists and specialists in church and social history, tells a vastly more complicated, interesting and indeterminate story … it is simply untrue to assert that classical culture was ever lost, ignored or suppressed during the Middle Ages … The Swerve claimed for itself, and received, huge moral and cultural authority it simply didn’t earn.

In 2016, Greenblatt won the prestigious international Holberg Prize, “awarded annually to scholars who have made outstanding contributions to research in the humanities, social sciences, law or theology,” prompting Laura Saetveit Miles, a Professor at the University of Bergen, to write that “The Swerve doesn’t promote the humanities to a broader public so much as it deviously precipitates the decline of the humanities, by dumbing down the complexities of history and religion in a way that sets a deeply unfortunate precedent.

If Greenblatt’s story resonates with its many readers, it is surely because it echoes stubborn, made-for-TV representations of medieval “barbarity” that have no business in a nonfiction book, much less one by a Harvard professor.

. . .

And as I read, the normal person inside me thought: It is important for academics to write in this accessible style and reach broader audiences with stories about the past! This is the great story of modernity!

When I finished, I put down The Swerve on the table, and the academic side of my brain kicked back in. I had let myself read it as fiction. Yet it was supposed to be not fiction. When I thought of it as a scholarly book, and thought of all those thousands and thousands of people out there who read it and believed every word because the author is an authority and wins prizes, I realized: This book is dangerous.

Dangerous or not, a lot of people read it—and it stands in for the ongoing question of why we read things in this decade, and what pleasurable writing allows us to ignore (or accept).

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

When Lytle was born, the Wright Brothers had not yet achieved a working design. When he died, Voyager 2 was exiting the solar system. What does one do with the coexistence of those details in a lifetime’s view? It weighed on him.

*

Essential stats: While not a major bestseller like some of the other books on this list, Pulphead was widely adored by both readers and critics—and its best essay, “Mister Lytle” won a National Magazine Award and a 2011 Pushcart Prize.

What did the critics say? They were universally on board. “In January, John Jeremiah Sullivan entered my life like a crashing meteor,” Ed Caesar wrote in the Sunday Times. “My reaction—and, I now discover, the reaction of many new arrivals at the church of John Jeremiah—was simple and confounded: where had this guy been all our lives?”

What made it defining? As I’ve written before, Pulphead was emblematic of a resurgence of the American essay as a popular literary form. Plus, it touches a lot of American life. Plus plus, it’s devastatingly good.

As a public service, here’s where to read that essay: “Mister Lytle: An Essay”

Tina Fey, Bossypants (2011)

If you retain nothing else, always remember the most important rule of beauty, which is: who cares?

*

Essential stats: After a reported $6 million advance, Bossypants sold 3.75 million copies in 5 years. No slouch, Tina.

Why was it defining? It kind of opened the floodgates—or as US News put it, “confirmed a market” for sharp, funny, nonfiction by female comedians, like Mindy Kaling’s Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (2011) and Amy Poehler’s Yes Please (2014). At the very least, it’s one of the best, if not the very best, of that rapidly-expanding genre. “Bossypants isn’t a memoir,” Janet Maslin wrote. “It’s a spiky blend of humor, introspection, critical thinking and Nora Ephron-isms for a new generation.” And for at least some of the new generation, it’s worked.

Here’s an excerpt from the audiobook, which also sold like crazy on Audible:

Ernest Cline, Ready Player One (2011)

You’d be amazed how much research you can get done when you have no life whatsoever.

*

Essential stats: Ernest Cline’s big-hearted, 80s nostalgia-sodden, gleefully nerdy debut novel—which tells the story of an orphan teenage boy in a dystopian United States who enters a worldwide VR game in search of an Easter egg that promises a fortune to the finder—was a New York Times bestseller, translated into twenty languages, and made Cline, in the words of USA Today’s Oldenburg, “the hottest geek on the planet.”

So how many 80s pop culture references does the book contain? So, so many. A ludicrous amount, really. Everything from The A-Team to WarGames, Pac-Man to The Breakfast Club, Donkey Kong to Heathers. If you’re so inclined, you can scroll through this complete list.

What of the inevitable movie adaptation? Thankfully, Steven Spielberg snapped up the rights before Moby could, and last year turned Cline’s puzzle box labor of love into a $175 million CGI juggernaut which, though certainly not without its critics, was generally well-received and grossed $580 million.

If you’re hungry for even more 80s geekery and meta shenanigans: Will Wheaton (of Star Trek: The Next Generation fame), who is mentioned briefly in one of the chapters, narrates the audiobook.

And perhaps you would like to have every single video game in the book explained for you?

–DS

Andy Weir, The Martian (2011)

Yes, of course duct tape works in a near-vacuum. Duct tape works anywhere. Duct tape is magic and should be worshiped.

*

Essential stats: Weir’s self-published “nerd thriller” became a bestseller before it was even a book, and then once it was a book, it became an even bigger bestseller (we’re talking #1 New York Times bestseller), and then a huge blockbuster movie. No big deal.

What makes it defining? This was a decade of digital DIY, in which you could build a brand from your living room and get internet famous, which then sometimes translated to actual famous. Not able to get a literary agent, Weir self-published The Martian on his website in serial form in 2011, and eventually, after requests from readers who wanted to download it to their Kindles, put it on Amazon, for 99 cents, the lowest price the site allows. He sold 35,000 copies in three months. He signed with a literary agent, and Crown Publishing purchased the rights to the book for six figures and re-released it in 2014, and then Ridley Scott adapted it into a film starring Matt Damon in 2015.

Speaking of Matt Damon: Someone actually calculated the (fictional) cost of rescuing Matt Damon over the years. It’s . . . a lot.

Courage Under Fire (Gulf War 1 helicopter rescue): $300k

Saving Private Ryan (WW2 Europe search party): $100k

Titan A.E. (Earth evacuation spaceship): $200B

Syriana (Middle East private security return flight): $50k

Green Zone (US Army transport from Middle East): $50k

Elysium (Space station security deployment and damages): $100m

Interstellar (Interstellar spaceship): $500B

The Martian (Mars mission): $200B

TOTAL: $900B plus change

Denis Johnson, Train Dreams (2011)

He liked the grand size of things in the woods, the feeling of being lost and far away, and the sense he had that with so many trees as wardens, no danger could find him.

*

Essential stats: Johnson’s novella was first published in the Summer 2002 issue of The Paris Review; in this version, it won the O. Henry Award and the Aga Khan Prize for fiction. When it was republished by FSG in 2011, it became a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer, though no prize was awarded that year (a travesty, we have all agreed, here in the Literary Hub office—though Michael Cunningham has tried to explain it somewhat). It’s the second-most revered book from one of contemporary literature’s most revered writers. It even made the bestseller list.

Why was it defining? Well, I like to believe that this decade was defined in some part by sheer literary excellence. Naive, I know—so I suppose I’ll have to say nostalgia. As K. Reed Petty put it over at Electric Literature:

According to the jacket copy of my edition of Train Dreams, Denis Johnson’s book “captures the disappearance of a distinctly American way of life.” That’s true, but the lost era this novella mourns isn’t the frontier life of our hero, Robert Grainier, in the early twentieth century. It’s 2006, or maybe 1998 or 1981, when we still believed in cowboys (and even called one President).

Train Dreams is a gorgeous, rich book about the classic American myth, but written for a country that’s lost faith in its own mythology.

And maybe it was defining because it wasn’t like anything else we had. And maybe because it was one of those books that a certain kind of person pushed into the hands of everyone they knew. There is some special magic in this book, that is all I know.

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011)

A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth. Authoritarian institutions and marketers have always known this fact.

*

Essential stats: This popular psychology book by Kahneman, laureate of the Nobel Prize in Economics, laid out two different ways the brain thinks—and what that means for our ability to reason and make choices. It was awarded the 2011 Los Angeles Book Prize, and the 2012 National Academies Communication Award, which recognized “excellence in reporting and communicating science, engineering, and medicine to the general public.” It was also a huge global bestseller, selling a million copies its first year.

What was its impact? As The Guardian put it, it “changed the way we think about thinking.” In a review of the book in The Globe and Mail, Janice Gross Stein wrote:

It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Daniel Kahneman’s contribution to the understanding of the way we think and choose. He stands among the giants, a weaver of the threads of Charles Darwin, Adam Smith and Sigmund Freud. Arguably the most important psychologist in history, Kahneman has reshaped cognitive psychology, the analysis of rationality and reason, the understanding of risk and the study of happiness and well-being. He is among a handful of founders of the field of behavioral economics, a branch of economics that is challenging long-standing economic theory and reshaping the making of public policy. Kahneman’s work speaks to everyone who struggles to understand why human beings think the way they do.

For his part, Steven Pinker called him “the world’s most influential living psychologist,” and told The Guardian that

he pretty much created the field of behavioral economics and has revolutionized large parts of cognitive psychology and social psychology. His central message could not be more important, namely, that human reason left to its own devices is apt to engage in a number of fallacies and systematic errors, so if we want to make better decisions in our personal lives and as a society, we ought to be aware of these biases and seek workarounds. That’s a powerful and important discovery.

But, he points out, while “Thinking, Fast and Slow is an interesting capstone to his career . . . his accomplishments were solidified well in advance of writing it and they’d be just as significant without the book. His work really is monumental in the history of thought.”

Here’s Kahneman’s 2010 TED Talk:

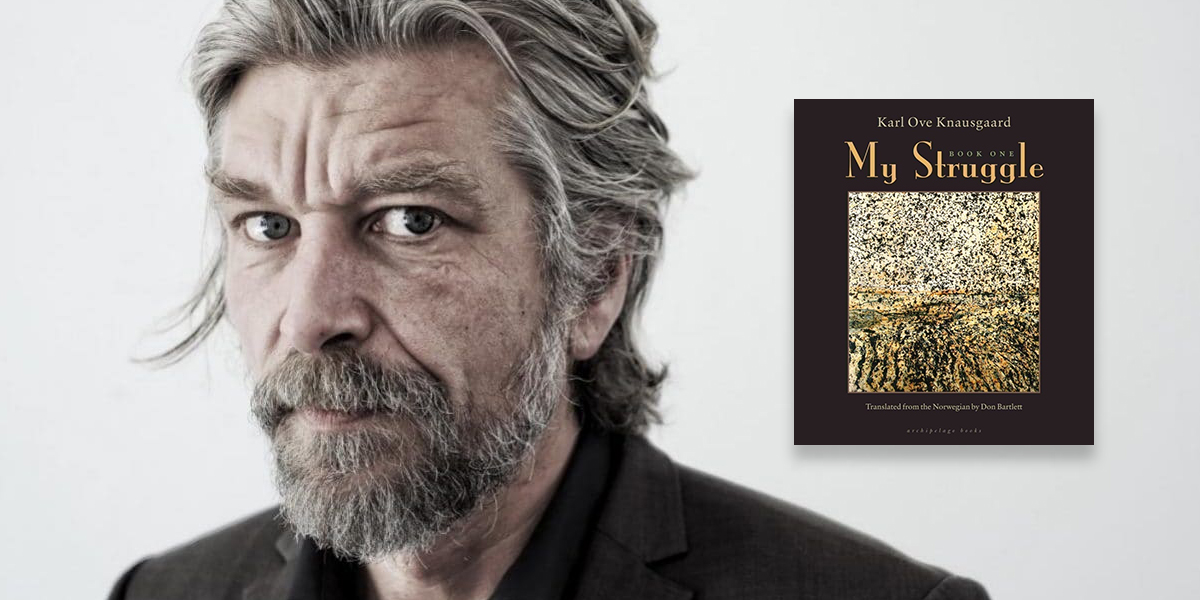

Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Don Bartlett, My Struggle: Book 1 (2012)

As your perspective of the world increases not only is the pain it inflicts on you less but also its meaning. Understanding the world requires you to take a certain distance from it. Things that are too small to see with the naked eye, such as molecules and atoms, we magnify. Things that are too large, such as cloud formations, river deltas, constellations, we reduce. At length we bring it within the scope of our senses and we stabilize it with fixer. When it has been fixed we call it knowledge.

*

Essential stats: the first of six books, which would total some 3,600 pages, and which were massive bestsellers in his native Norway, put up modest sales in the US and UK but had outsize impact on the literary landscape.

Why was it defining? A Knausgaard stand-in appeared on Younger feeding candy to Hannah Montana in Sockerbit, which is how, if you’re any sort of publishing-adjacent person, you really know you’ve made it:

Why was it really defining? There are only a few modes of literature that could be said to have definitively defined the decade, and one of them is “autofiction,” of which Knausgaard is the Platonic ideal—or as John Williams put it, “the sun in this genre’s planetary system.” Tying the My Struggle series to Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels (see below), Charles Finch recently wrote:

In overlapping moments, these two Europeans’ respective multivolume novels won huge rapid fame — for being highly personal, very long and perhaps more than anything for the unusual, almost guilty intensity with which people devoured them. (As The Times’s Dwight Garner memorably commented, reading the first volumes of Knausgaard’s My Struggle was like “falling into a malarial fever.”) Above all, they were close to identical in their most serious and unexpected offer to the reader: unmediated access, over many pages, to precisely one other consciousness.

. . .

Knausgaard and Ferrante promise so little. But they give it. Each recounts, in the close first person, the inside of a human life. That’s something innumerable writers have done, obviously, but they seemed to do it in a newly dangerous way — with a pitiless, dispassionate modesty of ambition. Neither narrator extrapolates larger truths from experience. Both trust themselves as far as their own fingertips; Ferrante portrays the intricate social world of working-class Naples, but in a state of constantly renewed bafflement, while Knausgaard (“He broke the sound barrier of the autobiographical novel,” the novelist Jeffrey Eugenides told a reporter for The New Republic) abandons almost all narrative pretense to describe his time on earth as straightforwardly as he can.

The effect this method had on me, and I believe on many people, was one of immediate trust and identification. Somewhere in the stretch between Sept. 11, 2001, and the 2016 election, such limited claims to certainty came to seem not unambitious, but like the only sane rejoinder to the world as it had become. And the length of the books — their uncompressed, occasionally boring plots — created a profound new version of the self-forgetting that the best stories give us.

But are the books amazing or boring? Both, I guess. General consensus in the literary office is that the first book is good, and that the rest of the series descends into annoying navel gazing. This writer’s belief is that the first paragraph of the first book is good, and the rest of the series descends into annoying navel gazing. Don’t @ me with your pearl clutching, Karl Ove stans.

Extra credit: Knausgaard on John Fosse · Knausgaard on ice cream · Knausgaard on writing

Sheila Heti, How Should a Person Be? (2012)

We live in an age of some really great blow-job artists. Every era has its art form. The nineteenth century, I know, was tops for the novel.

*

Essential stats: It was published in Canada in 2010, and in the US in 2012, after being turned down a bunch.

Why was it so important? How Should a Person Be? is one of the early examples of a literary mode that would itself define the decade: autofiction. It is subtitled “A Novel from Life,” which back in 2012 seemed necessary to explain, as David Haglund did:

What the phrase means to acknowledge is that the novel’s (occasional) action and (incessant) dialogue are largely, though not entirely, factual. The narrator is named Sheila, and the narrator’s friends share first names and occupations with Heti’s real-life friends and collaborators, among them the critic and artist Sholem Krishtalka, the writer and teacher Misha Glouberman (with whom Heti wrote a book of pop philosophy, “The Chairs Are Where the People Go,” published last year), and the painter and filmmaker Margaux Williamson — all of whom, like Heti, live in Toronto, where the book mostly takes place.

Critics couldn’t decide whether it was genius and groundbreaking or insufferable and navel-gazing, which sounds more or less like life to me.

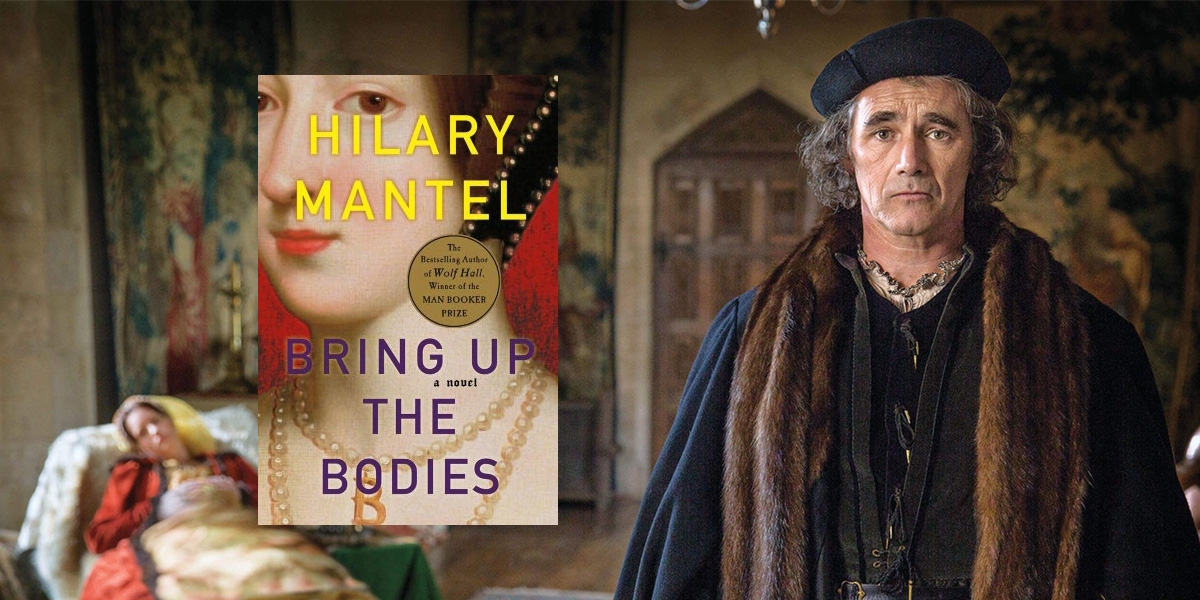

Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies (2012)

Truth can break the gates down, truth can howl in the street; unless truth is pleasing, personable and easy to like, she is condemned to stay whimpering at the back door.

*

Essential Stats: The second installment in Hilary Mantel’s barnstorming historical fiction trilogy was, like its predecessor, a bestselling, Booker Prize-winning blockbuster of a novel. It was critically-acclaimed, sold a million copies, and was made into a Golden Globe-winning BBC miniseries. It also won the Costa Book Award and was a finalist for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction.

People are really into sixteenth century English political intrigue then, huh? So it would appear. Thanks to Mantel’s gripping revivification of the court of King Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell has become one of the most iconic literary characters of the last decade.

It’s been nearly eight years. When will we get to read the concluding volume? Soon! The final part of the trilogy, The Mirror and the Light—which will cover the last four years of Cromwell’s life, from the death of Anne Boleyn to Cromwell’s own execution—is scheduled for release in March 2020.

Will Mantel take home the Booker for that one too? She’s on a serious hot streak, so quite possibly, but as Francis Ford Coppola, Sam Raimi, and the Wachowskis will tell you: it ain’t easy to stick the landing. Already the only woman to win the Booker twice, if The Mirror and the Light does go all the way, Mantel will become the first author in the Prize’s fifty-year history to three-peat.

Here’s the trailer for the Wolf Hall television show:

–DS

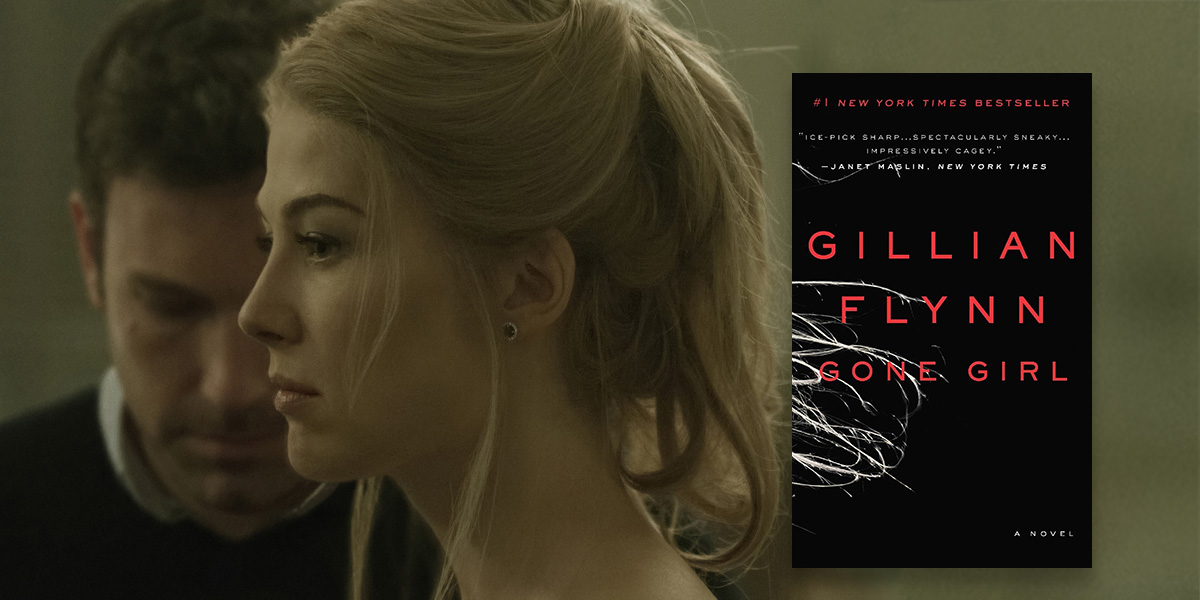

Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl (2012)

Cool Girl never gets angry at her man.

*

Essential stats: 432 pages; New York Times hardcover fiction #1 bestseller for 8 weeks; 26 weeks on NPR’s hardcover bestseller list; sold more than two million copies in the first year; adapted into a David Fincher movie with Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike; made being a “cool girl” way more frightening than it already was.

What made it a phenomenon? The unconventional plot twist, the unreliable (and very, very, bad) female protagonist, the paranoid portrayal of a marriage gone far far awry.

But is it actually any good? I’d say . . . yes. Despite the fact that my esteem for it began fading as soon as I finished the last page, I enjoyed the hell out of it while it lasted, and it certainly ticks a lot of boxes, including those marked “ingenious” and “scary” and “pretty sexy”. Not bad!

I mean, relatable:

Your girl Gillian on Armchair Expert:

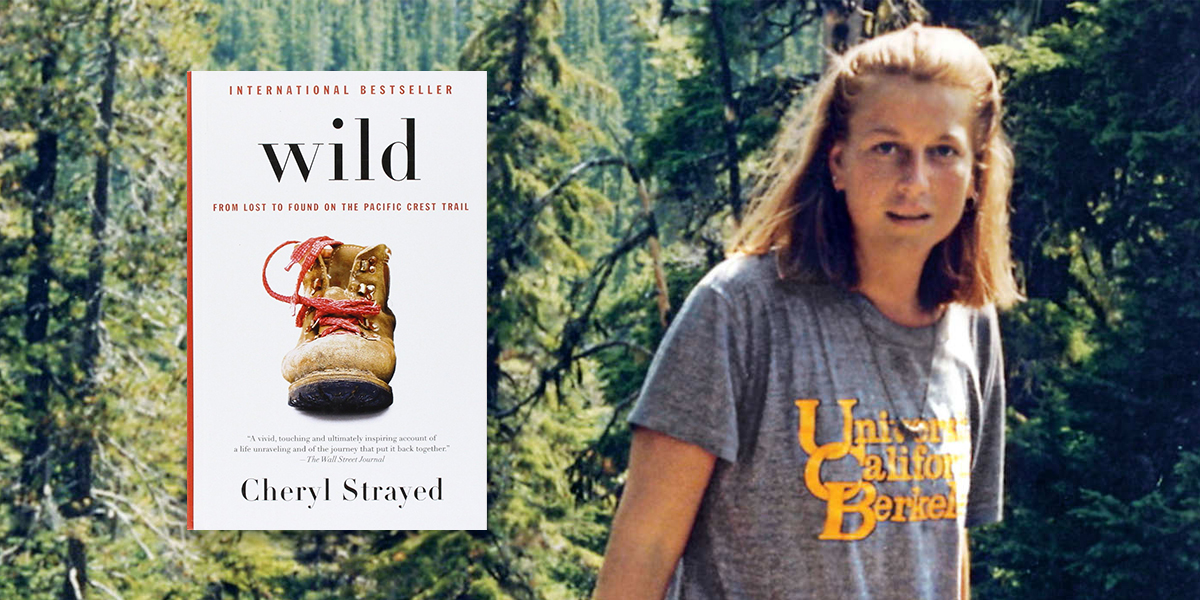

Cheryl Strayed, Wild (2012)

I knew that if I allowed fear to overtake me, my journey was doomed. Fear, to a great extent, is born of a story we tell ourselves, and so I chose to tell myself a different story from the one women are told. I decided I was safe. I was strong. I was brave. Nothing could vanquish me.

*

Essential stats: Everybody read this book, a memoir of Strayed’s turbulent youth and her hike along the Pacific Crest Trail. It was a #1 New York Times bestseller for 7 weeks and a general betseller for longer (the paperback, published in 2013, was on the list for 126 weeks), the first selection for Oprah’s Book Club 2.0., and adapted into a film by (and starring) Reese Witherspoon.

What’s its legacy? This is the book that launched a thousand hiking trips—including that of one Lorelai Gilmore, though to be fair, she doesn’t make it past the pissy park ranger in the recent Netflix revival of Gilmore Girls. The book also launched the career of Cheryl Strayed, who is also known as Dear Sugar. Plus, it’s pretty great. (Just ask Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub’s resident Wild mega-fan.)

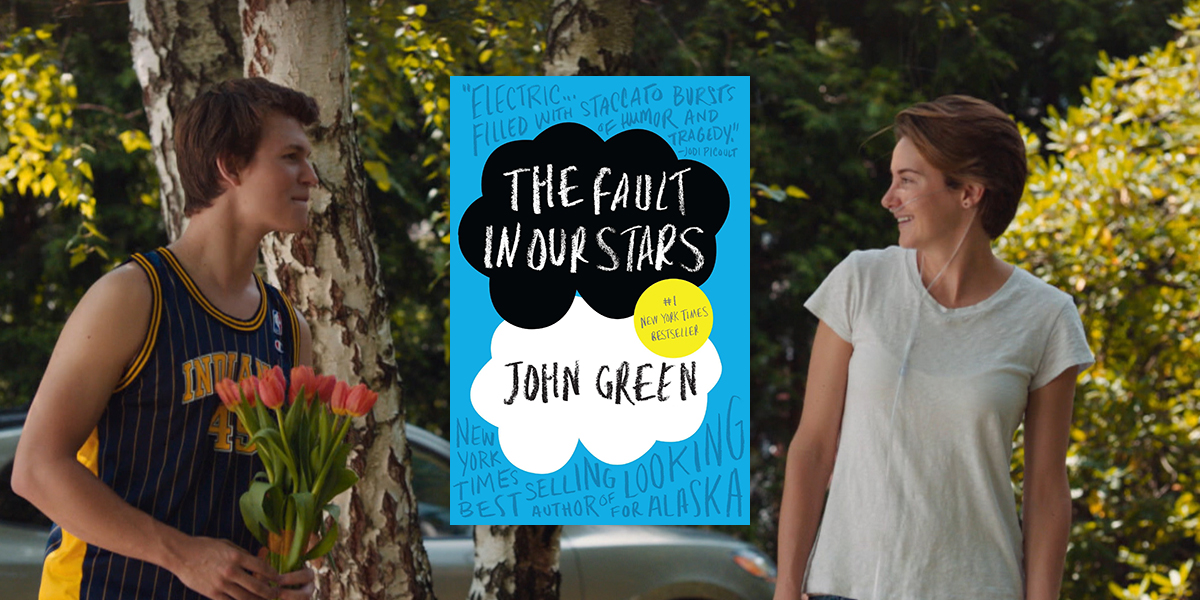

John Green, The Fault in Our Stars (2012)

Maybe okay will be our always.

*

Essential stats: When The Fault in Our Stars was published in 2012, John Green was already strongly A Thing. He had already published five other novels (his debut, Looking For Alaska won the Michael L. Printz Award in 2006) and he was a pioneering vlogger (please enjoy that two-word time capsule). The Fault in Our Stars is the story of two teenagers who meet at a cancer support group and fall in love. Tears were jerked, unrealistic expectations about high school relationships were set, and copies were sold. The book debuted at #1 on the New York Times Best Seller list for children’s chapter books, and held onto that spot for seven weeks. As of 2014, it had sold over 10 million copies.

Did the critics like it? Sure—they’re not made of stone! In her review at NPR, Rachel Syme said of Green: “[He] writes books for young adults, but his voice is so compulsively readable that it defies categorization. He writes for youth, rather than to them, and the difference is palpable.” Writing for Time, Lev Grossman called it “damn near genius.”

But did Willem Dafoe like it? Enough to appear in the 2014 film adaptation, along with Shailene Woodley, Ansel Elgort, and Laura Dern.

Okay?

Okay.

–JG

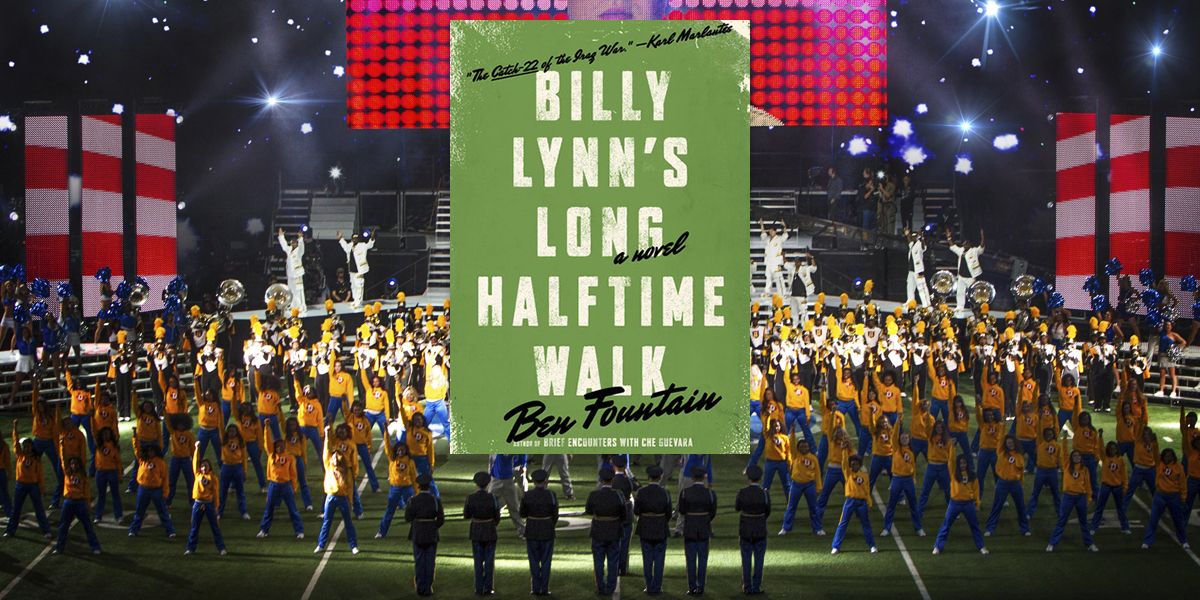

Ben Fountain, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2012)

Somewhere along the way America became a giant mall with a country attached.

*

Essential stats: This satirical war novel—about a group of Iraq War veterans who, after being captured on film embroiled in a brief but intense firefight, are hailed as heroes and sent on a surreal victory tour of the US—was a New York Times bestseller, won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and was a finalist for the National Book Award. It was also adapted into a feature film by Ang Lee.

Would you call it Catch-22 for the Iraq War generation? Well, Joseph Heller’s novel is more mad-cap and surreal, but they’re both biting examinations of how the American war machine is marketed and fed, so yes, I suppose I would.

Was it reviewed by any real-life veterans? Indeed it was. Reviewing the novel for the Daily Beast, author and Iraq War vet Matt Gallagher wrote of Billy Lynn:

This postmodern swirl of inner substance, yellow ribbons, and good(ish) intentions is at the core of Ben Fountain’s brilliant Bush-era novel, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk… For more than a decade, service members have returned home from Iraq and Afghanistan to find themselves strangers in strange lands, from Disney World to the Mall of America to Texas Stadium. No, Billy Lynn isn’t satire topped with sprinkles of realism. It’s the exact opposite, and Fountain does an estimable job of channeling that experience and psychology. And he does so not with the wit and winking of the jester, but with the blunt ferocity of the herald.

What happened with the film adaptation? It was the first ever feature film using an extra-high frame rate of 120 frames per second (?), which presented a significant number of logistical challenges for Lee and his team, from the cast not being able to wear make-up or utilize traditional film lighting to the realization that only five theaters in the entire world were equipped to show it at its highest resolution and maximum frame rate. While it did receive some positive reviews, overall critics and audiences were left a little cold by Lee’s technological innovations.

Here’s the trailer, in case you haven’t seen it:

–DS

Edward St. Aubyn, The Patrick Melrose Novels (2012)

People never remember happiness with the care that they lavish on preserving every detail of their suffering.

*

Essential stats: This Picador omnibus contains the first four Patrick Melrose novels: Never Mind, Bad News, Some Hope, and Mother’s Milk.

Hang on, aren’t these books from the ’90s? Well, yes. St. Aubyn first published Never Mind, the first novel in the series, in 1992—but it was the publication of this garishly-colored omnibus in 2012 that turned the underground whispers I had been hearing forever into roars. Plus, as it was meant to, it fast-tracked readers to At Last, the final installment of the Patrick Melrose saga, which also came out in 2012.

And then, of course, there was the BBC miniseries, a 2018 Benedict Cumberbatch passion project that brought even more attention to the quietly perfect books.

So what makes them defining? In the decade of autofiction, they both were and weren’t—they offered an alternate path to the Knausgaard/Heti/Lerner mode: a much more British one. Plus, for a while there it felt like there were only two types of people: those who loved the Patrick Melrose novels, and those who had never heard of them.

Susan Cain, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking (2012)

There’s zero correlation between being the best talker and having the best ideas.

*

Essential stats: Cain’s accessible explainer, or as one critic put it, “part affirmation, part social commentary, part self-help primer,” on introversion—and how the world (and especially the workplace) is set up to reward extraversion instead—was on the hardcover bestseller list for 16 weeks, and in paperback, it hung on for 138 weeks. By 2015, it had sold 2 million copies worldwide.

What was its impact? It seems like common knowledge now, but many people had never been aware of the true differences between introverts and extroverts before reading—or hearing about—this book. Anecdotally, I know several people who read it and felt like something about their lives had finally been solved, and non-anecdotally, they weren’t alone. Cain’s book did a lot to popularize the term, and certainly to help it enter our everyday lexicon: as Laura M. Holson writes in The New York Times, “it is at least partly because of her efforts that The Huffington Post, BuzzFeed and the like are now teeming with personality quizzes and posts like Can You Survive This Party as an Introvert? and 26 Cat Reactions Every Introvert Will Understand.”

Cain’s TED talk on the power of introverts:

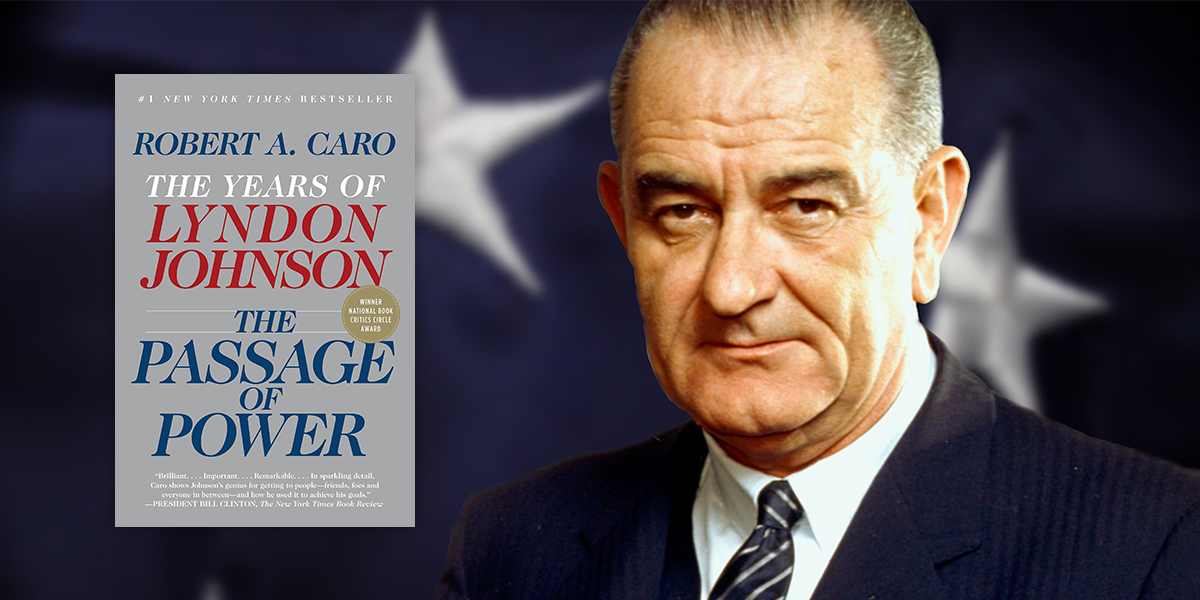

Robert A. Caro, The Passage of Power (2012)

Ask not what you have done for Lyndon Johnson, but what you have done for him lately.

*

Essential stats: The 736-page tome won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize (2012; Biography), the Mark Lynton History Prize, the American History Book Prize, and the Biographers International Organization’s Plutarch Award, and was a finalist for the National Book Award for Nonfiction. Whew.

Um, LBJ in the 2010s? Yes, obviously this is a history book about LBJ, the final installment in the series Caro began in 1982, so it’s not as immediately topical or groundbreaking as some of the others on the list, but it is widely acknowledged as Caro’s masterpiece, and is certainly one of the best history books of the decade. As our own Molly Odintz wrote:

There’s something profoundly moving about the vastness of these works—Caro is 83 now, and has dedicated an enormous part of his life to this singular project. His wife is his only approved research assistant, and together, they’ve upended half a century of LBJ criticism to reveal the complex, problematic, but always striving core of a sensitive soul.

Here’s Caro speaking at the LBJ library:

Chris Ware, Building Stories (2012)

It’s somehow more comforting to imagine that one’s suffering is unique, and to measure against what one doesn’t know, rather than against what one does.

*

Essential stats: Ware’s 2012 graphic novel—er, graphic box full of 14 “easily misplaced elements” that can be read in any order—was published 12 years after Jimmy Corrigan and was widely hailed as his masterpiece; it won him a slew of awards, including an Eisner Award (the National Book Award of the comics world) and the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize.

Wait, a box? Yep. Building Stories was as much a triumph of form as of storytelling, a thumbed nose at an increasingly digital reading world. It came in a box, and in the box, a series of books and leaflets in varying sizes. “The organizing principle of Building Stories is architecture, and — even more than he usually does — Ware renders places and events alike as architectural diagrams,” writes Douglas Wolk in The New York Times Book Review.

He’s certain of every detail of these rooms, and tends to splay their furnishings out diagonally to show how they fit together. Every visual observation of bodies or nature is ruthlessly adjusted to the level of symbol, rendered in a minimal number of hard, perfectly even, perfectly straight or curved lines. Elaborate strings of micro-panels explode scenes’ components outward through time or through a character’s thought patterns; mandala-ish page compositions arrange associative chains of text and pictures around a central image. The florist’s young daughter appears, practically life-size, at the middle of one of the biggest double-page sequences in the book.

I still don’t really get it? This should help:

Elena Ferrante, tr. Ann Goldstein, The Neapolitan Novels (2012-2015)

“I feel no nostalgia for our childhood: it was full of violence. Every sort of thing happened, at home and outside, every day, but I don’t recall having ever thought that the life we had there was particularly bad. Life was like that, that’s all, we grew up with the duty to make it difficult for others before they made it difficult for us.”

*

Essential stats: 4 books*, one long story, all bestsellers. Plus, a gorgeous HBO adaptation that . . . not that many people talked about for some reason. (Is it that hard to read subtitles?) Merve Emre called My Brilliant Friend “not just any novel, but a novel that had surpassed ordinary best-seller status to emerge, instead, as an event, a sensation, a literary pathology: “Ferrante fever,” as readers had taken to calling the frenzy that greeted the publication of each Neapolitan novel—the midnight-release parties; the grave discussions about the books’ covers; the jostling reviews, with each critic claiming to know her art more intimately than the critic who came before.”

*For the record: My Brilliant Friend (2012), The Story of a New Name (2013), Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014), and The Story of the Lost Child (2015)

What made them a phenomenon? Books as highbrow soap opera. Decades-long epic about women. Female friendship, female friendship, female friendship.

Speaking of Ferrante fever: Don’t pretend you didn’t have it. Maybe you even watched the documentary:

And it isn’t over.

Definitely related: DON’T COME FOR ELENA, doxxers. Seriously.

Expert’s tip: The Days of Abandonment is secretly better. And a lot shorter. Don’t @ me.

Extra credit: Elena Ferrante: Master of the Epic Anti-Epic · Ann Goldstein on Translating Elena Ferrante · Naples, The Reading List: Your Guide to the City of Elena Ferrante.

Malala Yousafzai, I Am Malala (2013)

We realize the importance of our voices only when we are silenced.

*

Essential Stats: This inspirational autobiography by the young Pakistani activist and Nobel laureate (who was shot by the Taliban for standing up for female education) has been translated into over forty languages, sold over two million copies, and been banned in Yousafzai’s home country.

Fun Audio Book Fact: The audio book edition of I Am Malala, narrated by the writer and activist Neela Vaswani, won the 2015 Grammy Award for Best Children’s Album.

What’s Malala Yousafzai up to now? As well as continuing to break down barriers preventing more than 130 million girls around the world from going to school though her work at the Malala Fund, Yousafzai is currently studying Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at Oxford University.

Watch Yousafzai’s Nobel Prize speech here:

–DS

Donna Tartt, The Goldfinch (2013)

Caring too much for objects can destroy you. Only—if you care for a thing enough, it takes on a life of its own, doesn’t it? And isn’t the whole point of things—beautiful things—that they connect you to some larger beauty?

*

Essential stats: Tartt’s longest, most Dickensian novel was, of course, an international #1 bestseller, and spent more than 30 weeks on the New York Times list, selling some million and a half copies in the first year. It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction in 2014, and was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Baileys Women’s Prize.

Why was it defining? Well, the revered lady Tartt only blesses us with a novel once a decade, so every time she does it’s a major event. But this novel was more than that: it was without question the most anticipated and discussed novel of the year—so big that even the Frick, a stuffy (if lovely) museum in New York City that happened to have the painting in question on hand, became a major tourist destination.

But it also sharply divided critics. As Evgenia Peretz put it in Vanity Fair, in addition to the mountains of praise (and, you know, that Pulitzer) the book also received “some of the severest pans in memory from the country’s most important critics and sparked a full-on debate in which the naysayers believe that nothing less is at stake than the future of reading itself.”

Wait, what happened to the future of reading? Spoiler alert: it’s still there.

Okay, whew, go on: Michiko Kakutani loved it, citing “the Russian masters” and calling it “enthralling.” James Wood sniffed in The New Yorker that it was “a virtual baby: it clutches and releases the most fantastical toys,” but also that it was for babies: “Its tone, language, and story belong to children’s literature.” After Tartt was awarded the Pulitzer, Wood told Vanity Fair: “I think that the rapture with which this novel has been received is further proof of the infantilization of our literary culture: a world in which adults go around reading Harry Potter.” Yikes.

As Peretz wrote, “No novel gets uniformly enthusiastic reviews, but the polarized responses to The Goldfinch lead to the long-debated questions: What makes a work literature, and who gets to decide?” That is, is it about the story, or the way the story is told? Is it about what the critics think, or what the readers think? The answer, of course, is that it is about all of these, and none, and everyone should just decide for themselves what they like and leave it at that.

To cap things off, there’s the terrible film adaptation:

But hey, seriously, friend to friend, is the book any good? As a reasonably well-read senior editor at a literary website and the most devoted fan of The Secret History there ever was, I say: I mean, it could have used some more editing. But boy was it fun.

Lawrence Wright, Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief (2013)

He could easily invent an elaborate, plausible universe. But it is one thing to make that universe believable, and another to believe it. That is the difference between art and religion.

*

Essential stats: Wright’s exposé of Scientology, for which he talked to some 200 “current and former Scientologists,” was the natural extension of his shocking profile of film director and screenwriter Paul Haggis (who got “all the way to the top” of the Church of Scientology, and resigned after the church’s support of Prop 8, and therefore talked to Wright), which he published to much awe and attention in The New Yorker in 2011. When Going Clear was published in 2013, it was a finalist for both the National Book Awards and the National Book Critics Circle Awards, and it became the basis for a 2015 HBO documentary film directed by Alex Gibney.

What’s so defining about it? This book the reason a lot of people even know about Scientology, much less any of the details. In The New York Review of Books, Diane Johnson called it “a true horror story, the most comprehensive among a number of books published on the subject in the past few years,” and wrote that Wright seems to have a particular ability to understand and explain issues related to religion, recovered memory, fanaticism, “and deviance—and the nerve to withstand objections and threats. With this set of qualifications, he is able to put Scientology into its broadly American social setting.” Americans took notice.