10 Works of Literary Fiction

for Runners

Read Along With Your New Pandemic Workout

Over the past few months, as gyms and yoga studios and fitness centers have remained closed, many of you antsy yogis and barre-enthusiasts and Zumba-addicts have gone back to that most elemental of exercises: the run. For those of us who like to read and run, well, plenty of books on the subject come out every year, but while there are wonderful memoirs, essays, and other works of nonfiction dedicated to putting one foot in front of the other at speed, I always think there are fewer works of fiction than there should be. Luckily, what’s there is good—so if you’re looking to read something to boost your new running routine, or just help you cool down, here are some suggestions, from contemporary short story collections to LGBTQ cult classics (okay, just one of those), complete with running-centric quotations to help you choose. And feel free to add onto this (incomplete, always incomplete) list in the comments!

Jamie Quatro, “Ladies and Gentleman of the Pavement,” collected in I Want to Show You More (2013)

You take up running. You enjoy it. You get faster. Maybe you try a few shorter races: 5K, 10K, half-marathon. Eventually, you want to run the full 26.2. And the minute you sign up, bang, you get a statue in the mail. You have no idea what your statue will look like, though the majority are sexual: half-human, half-animal sculptures doing lewd things with their bodies. Creatures with hideously sized phalluses. These types of statues used to shock spectators, startle other runners into a slower pace. Now they’re so commonplace you feel nothing when you see them.

Lauren Groff, The Monsters of Templeton (2008)

We run; we like to run; we have run together for twenty-nine years now; we will run until we can run no more. Until our hips click and shatter apart, until our lungs revolt and bleed. Until we pass from middle age into old age, as we once passed from youth into middle age. Running. In the winter, we run, through the soft snow, slipping over the ice. In the Templeton summer, soft as chamois, glowing from within, we run. We run in the morning, when the beauty of our town gives us pause. When it is ours and ours alone, the tourists still tunneling into their dreams of baseball, of Clydesdales, of golf. Oh, the beauty of the town, oh the sunrise over the town as we crest the hill by the gym all spread before us like a feast, our hospital with its fingerlike smokestack, beyond, the lake like a chip of serpentine, and the baseball museum, and the Farmer’s Museum, and the hills, and in the foggy hollow, our houses, fanned across the town, where, inside, our families sleep, peaceful. But we, the Running Buds, are together, moving, we behold this as we have beheld it for twenty-nine summers, twenty-nine winters, twenty-nine springs and falls.

Toni Cade Bambara, “Raymond’s Run,” collected in Gorilla, My Love (1992)

There is no track meet that I don’t win the first place medal. I used to win the twenty-yard dash when I was a little kid in kindergarten. Nowadays, it’s the fifty-yard dash. And tomorrow I’m subject to run the quarter-meter relay all by myself and come in first, second, and third. The big kids call me Mercury cause I’m the swiftest thing in the neighborhood. Everybody knows that—except two people who know better, my father and me. He can beat me to Amsterdam Avenue with me having a two fire hydrant headstart and him running with his hands in his pockets and whistling. But that’s private information. Cause can you imagine some thirty-five-year-old man stuffing himself into PAL shorts to race little kids? So as far as everyone’s concerned, I’m the fastest and that goes for Gretchen, too, who has put out the tale that she is going to win the first-place medal this year. Ridiculous. In the second place, she’s got short legs. In the third place, she’s got freckles. In the first place, no one can beat me and that’s all there is to it.

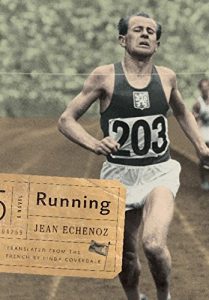

Jean Echenoz, tr. Linda Coverdale, Running (2009)

There are runners who seem to fly, others who seem to dance, still others who look as if they were parading, and some appear to be advancing as though they were sitting on top of their legs. There are those who simply look as if they’ve been summoned and are hurrying as fast as possible. Emil, nothing like all that.

Emil, you’d think he was excavating, like a ditch digger, or digging deep into himself, as if he were in a trance. Ignoring every time-honored rule and any thought of elegance, Emil advances laboriously, in a jerky, tortured manner, all in fits and starts. He doesn’t hide the violence of his efforts, which shows in his wincing, grimacing, tetanized face, constantly contorted by a rictus quite painful to see. His features are twisted, as if torn by appalling suffering; sometimes his tongue sticks out. It’s as if he had a scorpion in each shoe, catapulting him on. He seems far away when he runs, terribly far away, concentrating so hard he’s not even there—except that he’s more there than anyone else; and hunkered down between his shoulders, on that neck always leaning in the same direction, his head bobs along endlessly, lolling and wobbling from side to side.

Alan Sillitoe, “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner,” collected in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (1987)

By the time I’m half-way through my morning course, when after a frost-bitten dawn I can see a phlegmy bit of sunlight hanging from the bare twigs of beech and sycamore, and when I’ve measured my half-way mark by the short-cut scrimmage down the steep bush-covered bank and into the sunken lane, when still there’s not a soul in sight and not a sound except the neighing of a piebald foal in a cottage stable that I can’t see, I get to thinking the deepest and daftest of all. The governor would have a fit if he could see me sliding down the bank because I could break my neck or ankle, but I can’t not do it because it’s the only risk I take and the only excitement I ever get, flying flat-out like one of them pterodactyls from the ‘Lost World’ I once heard on the wireless, crazy like a cut-balled cockerel, scratching myself to bits and almost letting myself go but not quite. It’s the most wonderful minute because there’s not one thought or word or picture of anything in my head while I’m going down. I’m empty, as empty as I was before I was born, and I don’t let myself go, I suppose, because whatever it is that’s farthest down inside me don’t want me to die or hurt myself bad.

Mark Slouka, Brewster (2013)

There was no gun. We lined up in the gusty wind, Falvo standing in the soggy infield in his dress shoes holding his clipboard like a small high table against his chest with his left hand and his stopwatch in his right and then he barked, “Runners . . . marks? Go!”

They didn’t run, they flowed—the kid in the headband, the red-headed kid, and two or three others in particular—with a quiet, aggressive, sustained power that looked like nothing but felt like murder and I was with them and then halfway through the third turn they were moving away smooth as water and I could hear them talking among themselves, joking, Bullshit—Lisa Arrone? I swear to God, she just reaches in and I’m—and I was slowing, burning, leaning back like there was a rope around my neck. “Too fast, Mosher, too fast,” I heard Falvo yelling, and his ax-sharp face came out of nowhere looking almost frantic and then it was gone and there was just the sound of my breathing and the crunch of my sneakers slapping the dirt. The group, still in a tight cluster, wasn’t all that far ahead of me.

Andre Dubus, “The Cross Country Runner,” collected in The Cross Country Runner (2018)

He had always been a runner: in high school and college he had run the cross-country, in the Marine Corps he was an infantry officer and proudly and mercilessly he ran his platoon over the dusty fire trails at Camp Pendleton. For four years now he had been splitting his teaching day by running two miles at noon. It rarely failed to have a cathartic effect: somewhere after the first half mile, the jarring of his feet would shatter all his thoughts and they would be sloughed off, as if each bead of sweat contained a fragment of thought, of memory.

Naomi Benaron, Running the Rift (2010)

The runner squinted into the sun, and a field of wrinkles mapped his eyes. “No wonder, then. Do you know who you are named for?”

“The god who brings the thunder,” Jean Patrick said.

“Yes—Nkuba, Lord of Heaven, the Swift One.” Telesphore touched Jean Patrick below tthe left eye. “I see it there: the hunger. Sometday you will need to run as much as you need to breathe.”

Jason Reynolds, Ghost (2016)

I wish I could tell you what I was thinking. But I can’t. I probably wasn’t thinking nothing. Just moving. Man, were my legs going! I pumped and pushed, my ankles loose and wobbly in my sneakers, my jeans stiff and hot, the whole time seeing Lu out the corner of mmy eye like a white blur. And then it was over. And everybody watching, all the other runners, clapped and hooted, pointed at us both. Some had their mouths open. Others just looked confused. The lady on the other side of the track—not a peep. But all the people around her were standing and cheering.

Patricia Nell Warren, The Front Runner (1974)

I loved competition, and pitting myself against the other boys. But running was also good for its own sake—the discipline and the joy of motion. And physically, running made me different from boys (especially the fat, pampered ones, whom I despised) who didn’t engage in high-stress sports. Very early, I got to thinking of myself, and of all runners, as a separate and superior species of human begin.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.