10 new books to look out for this week.

Every week, the TBR pile grows a little bit more. It’s getting precarious. It’s taking up your whole nightstand. It’s threatening to crush you in your sleep. Well, what are you waiting for? Get cracking. What are you reading this week?

FICTION

Garth Greenwell, Cleanness

Garth Greenwell, Cleanness

(FSG)

“Oh god,” I yelled out on page three of this novel. My husband poked his head into the bedroom. “What?” I buried my face, in distress, in literary ecstasy, in relief. “I just love him so much,” I said. “He’s still so good. The sentences!” “Ok dear,” said the retracting head. But the intense elegance of Garth Greenwell’s prose—even when he’s describing rough sex or embarrassing passes or drunkenness—always startles me. It’s insane that anyone should be this good at writing, that anyone should be able to stir up the emotions of strangers so quickly, so deftly. This novel, like Greenwell’s first, What Belongs to You, is set mostly in Sofia, Bulgaria; also like his first, it is a profound meditation on love and ways to love; also like his first, it is sad, beautiful, and cathartic. It may stir up feelings you didn’t know you had, or those you didn’t want to face. But you’ll be glad you did, in the end.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

Ani Katz, A Good Man

Ani Katz, A Good Man

(Penguin Books)

When a book comes out with a title like this one has, you know it’s going to be about someone truly terrible. I’ve often thought about crime fiction is the art of the excuse—a skilled crime writer knows how to both show a character’s bad behavior and demonstrate the justifications used by that character to justify their behavior. In Katz’s mature and wicked debut, we encounter a man who’s slowly crumpling under the pressure of his mounting debts and need for perfection. He’s done something bad—but how bad is difficult to imagine. So, too, is the dark past that informs the actions of the present. Katz’s debut evokes Highsmith’s Ripley, or Denise Mina’s The Long Drop, and heralds the entry of a fantastic new voice to the genre.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads associate editor

Vikram Paralkar, Night Theater

Vikram Paralkar, Night Theater

(Catapult)

A teacher, his pregnant wife, and their young son walk into a clinic late one night. It sounds like the start of a joke, but it’s actually the start of a wildly surreal novel, in which this family tells the surgeon that they have been killed and given a chance to come back to life, if he can mend their wounds by sunrise. (We love an ominous one-night-only challenge!) Written by an actual physician-scientist, Night Theater drudges up ethical/existential questions and a whole lot of wonder.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

Joanna Kavenna, Zed

Joanna Kavenna, Zed

(Doubleday)

This spooky thriller by England’s most brilliant mid-career novelist feels like an apocalyptic sequel to I, Robot directed by Samuel Beckett. It’s sometime in the near future and software giant Beetle has created a new algorithm so powerful, so good at surveilling us, that there are no more surprises. And of course, no free will. That is until one morning, Beetle employee Douglas Barley wakes to learn that a man has gone home after a hard night on the booze to murder his wife and family. What follows is a brilliant satire of how hard tech giants work to pretend what they’re doing is merely handing us a tool, when in fact they’ve scrambled the very functioning of our minds—which, originally, were meant to work together. Full of hilarious riffs on the way language itself fights back against control, and plot twists that seem to borrow from a gumshoe crime caper, Zed is a fabulously intelligent rejoinder to the idea that a tech dystopia is inevitable.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Zora Neale Hurston, Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick

Zora Neale Hurston, Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick

(Amistad)

Thank God for archives. In 2016, Amistad at last released Zora Neale Hurston’s Baracoon, which grew out of her interviews with Cudjoe Lewis, the last remaining survivor of the Middle Passage. The book, written in the 1940s, had languished unpublished in the Alain Locke collection archives at Howard University. Not long ago, a handful of short stories from very early in Hurston’s career also turned up in the infrequently visited stacks of a research library. Here they are now as Hitting a Straight Light with A Crooked Stick, and they do not need any dusting off.

Take Hurston’s first published story, “John Redding Goes to Sea,” issued in 1921 in Howard University’s literary journal, published the year after Hurston earned her associate’s degree, before leaving for New York. In the tale, a young boy who dreams of going to sea becomes upset when the twigs he imagines are boats are caught in the reeds at the bank. Attempting to console his son, John’s father inadvertently warns him that life might be getting used to things “getting tied up.” The older man then swiftly corrects himself. “Now, no, chile, doan be takin’ too much stock of what Ah say. Ah talks in parables sometimes.” Reading these stories now, it’s hard not to see Hurston herself inhabiting this exact contradiction—telling the reader something hard, then allowing the form’s necessary obliqueness to apologize if what she says hurts. Read longitudinally, eventually leaving Florida and coming to Harlem, the collection feels like a narrative-based parallel to Jacob Lawrence’s Migration series, only here there’s a variety of sound and texture to the gesture, as if Hurston knew from the beginning how important it was for sound to migrate too, from country to the city, from speech into books. As a result, in her pages, Harlem sounds more like itself: a place full of people from far away, trying and failing to unlearn where it was they were from.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

NONFICTION

Anna Wiener, Uncanny Valley

Anna Wiener, Uncanny Valley

(MCD)

There are lots of memoirs about the tech industry, but Anna Wiener’s “literary-minded outsider’s insider account” does more than reveal the surreal extravagance of tech-bros in Silicon Valley. Wiener tracks her own motivations for leaving her publishing job in New York, the promises of the digital economy, and the promise of the utopian future that economy claims to want to build. Come for the unmasking of start-up culture, stay for the personal narrative of aspiration and disillusionment.

–Emily Firetog, Lit Hub deputy editor

Jennifer S. Hirsch and Shamus Khan, Sexual Citizens

Jennifer S. Hirsch and Shamus Khan, Sexual Citizens

(W. W. Norton)

The last few years have brought a renewed public conversation around sexual assault on college campuses, involving both a reconsideration of the legal landscape around it and a debate about the language we use to enact it. In Sexual Citizens, Jennifer S. Hirsch and Shamus Khan discuss the ways that social environments can exacerbate the risk factors for assault, drawing from the Sexual Health Initiative to Foster Transformation (SHIFT) at Columbia University and stressing the roles of cultural norms and gendered power structures. Their book promises to add important insight to a complicated, often-maligned set of issues, and I’m curious to see what they have discovered.

–Corinne Segal, Lit Hub senior editor

James Wood, Serious Noticing

James Wood, Serious Noticing

(FSG)

James Wood has been writing criticism for 30 years now, but in America his impact emerged in the late 1990s, when The Broken Estate was published, his name built on skewering big-name writers. There was—and has always been—far more to his work than reputation hunting. As an essayist, his ability to climb inside a book and speak of it in the book’s own language is unparalleled. Reading Serious Noticing, a selection of his work since 1999, is to watch Wood wrestle with tradition and new work in ways that feels intimate, hilarious, sometimes almost personal. Metaphors and similes animate each of these essays. “Chekov is more gloomily scrupulous than Hrabal,” Wood notes, “who likes to heat his caught enigmas.” “Krasznahorkai’s work tends to get passed around like rare currency,” he writes in another essay on the Hungarian cult writer. And of Helen Garner, “her unillusioned eye makes her clarity compulsive.”

Essay to essay, even when Wood tromps into the knee high snow drifts of high art, the action easily returns to those of us who live on earth. Perhaps it’s because reading is how Wood notices the world, and, in his own English way, loves it. Unlike his father, who became a priest in his fifties, Wood remains spiritually untethered, his Sundays as free as ever. So he reads. “Often in life,” he writes, “I have felt that an essentially novelistic understanding of motive has helped me to begin to fathom what someone else really wants from me, or another person. Sometimes it’s almost frightening to realize how poorly most people know themselves; it seems to put an almost priestly advantage over people’s souls. This is another way of suggesting that in fiction we have the great privilege of seeing how people make themselves up—how they construct themselves out of fictions and fantasies and then choose to repress or forget that element of themselves.”

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, Tightrope

Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, Tightrope

(Knopf)

In 2009, a Pulitzer Prize-winning couple penned Half the Sky, a work of investigative journalism dedicated to tracking the growing movement to empower women in the developing world. Ten years later, the husband-and-wife team is telling the story of real Americans, addressing the crisis of the working class, and searching for solutions to years of the government’s failure. As Sarah Smarsh wrote in The New York Times Book Review, “Yamhill is not reflected through a rearview mirror, distorted by a removed author’s guilt, resentment or nostalgia. Rather, it is conveyed up close by way of detailed reporting on living people … Together, their first-person ‘we’ has the refreshing effect of fogging the authorial ‘I’ and keeping the spotlight on those they’ve interviewed or memorialized.”

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

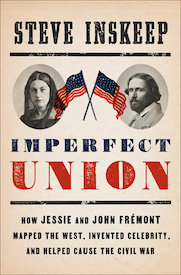

Steve Inskeep, Imperfect Union

Steve Inskeep, Imperfect Union

(Penguin Press)

From the host of NPR’s Morning Edition comes the story of the Frémonts, arguably America’s first great political couple. In the 1800s, this dangerous duo forged the way in westward expansion in the United States. Hamilton Cain raves about it in The Star Tribune, claiming, “Inskeep re-creates the darker currents beneath Manifest Destiny while rescuing John and Jessie from the margins of history.” Westward ho!

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

Katie Yee

Katie Yee is a Brooklyn-based writer.