10 Books You Should Read this July

Exile, Flesh-Eating Plants, and a Gender-Swapped Sherlock Holmes

Ashleigh Young, Can You Tolerate This?

(Riverhead)

In a book landscape of spectacle-driven nonfiction narratives, I am finding respite in Ashleigh Young’s perceptive and smart debut, Can You Tolerate This? It’s a collection of essays no less ambitious, sobering, or wide-ranging than the avalanche of social justice texts, but written with the tenderness and precision of a dentist who doesn’t use anesthesia. Speaking of landscapes, Young’s book inhabits her small hometown in New Zealand, which illuminates how observations of a place, over a long period of time, can shift the idea of spectacle itself. You can read an excerpt of Young’s book that appeared on Lit Hub last year as part of its series on 2017 Windham-Campbell Prize winners.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub contributing editor

Daisy Hildyard, The Second Body

(Fitzcarraldo Editions)

In The Second Body, Daisy Hildyard asks: How can we understand the ways our bodies exceed themselves? She cleverly coins the concept of “the second body,” a kind of shadow-self that accounts for the first body’s effect on all other life and on the world around it. In a series of rich, lucid meditations, rooted in conversations with others (butchers, biologists, etc.) and in illuminating readings of literature (Ferrante, Shakespeare, etc.), Hildyard guides the reader through questions about global warming, the illusive boundary between human and animal life, and more. The Second Body is a subtle, original attempt to see humanity more clearly.

–Nathan Goldman, Lit Hub contributor

Jonathan Santolefer, The Widower’s Notebook

(Penguin)

The short description of The Widower’s Notebook would be The Year of Magical Thinking from a male perspective. Both books are moving testimonials to grieving for a spouse who died suddenly, but Santofer’s book is not a mere copy of Didion’s. As Santofer found when he started writing the book, there are not many testaments by husband to their wives. He posits this is because of the way men are socialized: to stifle feelings and to be stoic in the face of calamity. Yet Santofer proves he’s unafraid of feeling the devastating emotion of his wife, Joy’s, death after a routine knee surgery. He took two years to write this beautiful and heartbreaking book, which is both a chronicle of a remarkably happy marriage and of the need to go on despite the worst possible thing happening.

–Lisa Levy, CrimeReads contributing editor

Claire O’Dell, A Study in Honor

(Harper Voyager)

As someone who came to my lifelong love of crime fiction through the character of Sherlock Holmes, I appreciate the seemingly infinite variations applied to the Sherlock narrative. Claire O’Dell’s futuristic take on the trilogy may be the most creative take of all. Set in the midst of a future civil war that has its roots in contemporary issues, and featuring two women of color as Watson and Sherlock, A Study in Honor follows Dr. Watson, a recently discharged army doctor with a robotic arm, as she moves in with Sara Holmes, a mysterious government agent, and the two investigate several mysterious deaths tied to a disastrous battle. If you like dystopian future narratives, queer romance, and Sherlock Holmes, you’ll adore A Study in Honor.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads editor

John Lingan, Homeplace: A Southern Town, a Country Legend, and the

Last Days of a Mountaintop Honky-Tonk

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

John Lingan’s Homeplace is a vivid, expertly rendered portrait of the many cultural threads running through Winchester, Virginia, the small Southern town where country music legend Patsy Cline was born. But Homeplace is also a larger exploration of America—of the long-building collisions that mark our calamitous present day. In a style reminiscent of John McPhee, Lingan writes lyrically and urgently. A fantastic debut work of literary nonfiction.

–Timothy Denevi, Lit Hub contributing editor

Brian Catling, The Cloven

(Vintage)

Beginning with The Vorrh, B. Catling has told a story in which very real histories and horrors of the 19th and 20th century—specifically, colonialism and war—are juxtaposed with a fantastical setting that draws upon elements of mythology and science fiction. The Cloven is the third book in Catling’s trilogy, incorporating World War II into the narrative. (Full disclosure: I’ll be in conversation with Catling at Greenlight Bookstore on July 30th.)

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

Roque Larraquy, Comemadre, trans. Heather Cleary

(Coffee House Press)

When the world is weird and maddening and warped, I turn to books that are even more so. I’m particularly excited to read Comemadre by Roque Larraquy. Like most stories, it is about love and life but I’ve also been promised mysterious ants, missing body parts, and flesh-eating plants.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

Beatriz Bracher, I Didn’t Talk, trans. Adam Morris

(New Directions)

“Look, I was tortured, and they say I snitched on a comrade,” the protagonist Gustavo says in this Brazilian novel set in São Paulo. Gustavo was one of many leftists who was brutally tortured or killed in Brazil in the 1970s. In this fictionalized account of a survivor, our protagonist is released back into the climate of totalitarian rule, suspicion, and intimidation. I Didn’t Talk is about the guilt and internal exile that takes place after survival. It is Bracher’s debut book in English and signals the arrival of a great new international voice.

–Nathan Scott McNamara

Ottessa Moshfegh, My Year of Rest and Relaxation

(Penguin Press)

Moshfegh is the captain of the horrible people—if writing them better than anyone makes you their captain, which I feel that it does. More importantly (but relatedly), I can’t remember the last time I read a book that gave me such nonstop pleasure. The narrator is self-absorbed, arrogant, broken, and determined to medicate herself into a coma. That’s pretty much the whole premise: she evades the affections of her despised best friend and scams various drugs out of her psychiatrist, working towards the combinations she’ll need to achieve her dream of sleeping for a year. That either makes sense to you or it doesn’t. If you read Twitter, or the news in any form, it probably does. Either way, you should read this book.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

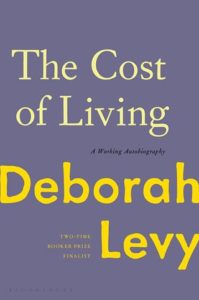

Deborah Levy, The Cost of Living

(Bloomsbury)

When Deborah Levy turned 50, her marriage ended, and a version of her life that she had never before anticipated living began. I’ve been eager to get my hands on her account of these events, The Cost of Living, since a barn-burning excerpt of it ran in the Guardian back in March. “To strip the wallpaper off the fairytale of The Family House in which the comfort and happiness of men and children has been the priority is to find behind it an unthanked, unloved, neglected, exhausted woman,” she writes. I am eager to read more about this stripping away, and all that Levy discovered beneath.

–Jess Bergman, Lit Hub features editor