10 Books by Czech Women We'd Like to See in English

The history of Czech literature in English is, to put it mildly, male-heavy

The fact that the translations we read in English are overwhelmingly by male authors is increasingly getting attention. For many, that realization began with Alison Anderson’s 2013 Words Without Borders article “Where Are the Women in Translation?” Advocacy and activism to change that fact have blossomed in the years since. In 2017, for the first time, a literary prize for women in English translation will be awarded.

The history of Czech literature in English translation is, to put it mildly, male-heavy. A bibliography covering the years 1832 to 1986 cites roughly 170 works by men versus 7 by women (the bibliography includes Slovak literature too, but these figures are just for works translated from Czech).

From 1987 to 2016, the disparity is not quite so mountainous, but we still see men published three times as often as women: 227 to 76. The disparity is even greater if we discount anthologies, some of which have been devoted entirely to women: 161 to 26—the proportion of women dropping from 33 percent to just 16.

It’s true we don’t have data on the proportion of women published in Czech to begin with. But so what? The point is, we live in a world that’s more or less 50-50 female-male, so why should our reading from other countries skew so heavily toward men?

Of course, we realize presses can’t publish what they don’t know exists, so to that end, we present these ten books by Czech women we’d love to see publishers pick up—and we think readers will love them too!

–Alex Zucker and Julia Sherwood

Milada Součková, Amor a Psyché (Amor and Psyche)

JTožička, 1937; reissued by ERM, 1995

Amor and Psyche is a fascinating experimental prose work structured as two diaries and a short novel. Using the diaries of two women, the student Augustina and the teacher Alžběta, to create a kind of double exposure, the novel playfully reflects the author’s own experience both as a student and as a beginning writer in search of new literary forms. Like most of Součková’s work, this novel blends unusual compositional techniques with historical and autobiographical qualities, inviting the reader to engage in a fascinating literary experience.

Why translate it?

Milada Součková (1899-1983) was associated with the Prague interwar artistic avant-garde and the famous Prague Linguistic Circle. After her immigration to the United States in 1948, she was best known for her work as a literary historian. Her prose and poetry became available to a broader Czech audience only when her writing was republished in Prague after 1989. Součková’s innovative style, which consciously works with the modern tradition of Woolf, Joyce and Proust, emphasizing the text as such, is an important antecedent to the work of several major contemporary Czech women writers, notably Věra Linhartová, Sylvie Richterová, and Daniela Hodrová. It is also a small but important part of the larger European 20th-century modernist tradition, which deserves to be available to the Anglophone reader.

–Elena Sokol

Kateřina Tučková, Vyhnání Gerty Schnirch (The Expulsion of Gerta Schnirch)

Host, 2009

Kateřina Tučková’s first novel, for which she won the 2010 Magnesia Litera Readers Award, begins in the Nazi-occupied city of Brno, in 1939, and follows the life journey of Gerta Schnirch, whose father is an ethnic German and mother a Czech. Gerta’s childhood is obliterated by World War II. After the war, she is caught in its brutal aftermath, during which the Czechoslovak government sanctioned the forced deportation and expulsion of ethnic Germans, leading to the death of some 15,000 of them. On the night of May 30, 1945, Gerta and her baby are rounded up with the other ethnic Germans remaining in Brno and forced to march toward the Austrian border. Pulled off the march to work in forced labor in a rural village in southern Moravia, Gerta and her daughter survive the postwar period and return to Brno, only to find themselves yet again marginalized by society, this time under the Communist regime. The novel continues through the year 2000, when official representatives of Brno were urged to issue a statement of disapproval for the actions of their predecessors and to offer a formal apology to the victims of the expulsion.

Why translate it?

This novel is written with a compelling zeal and engaging style that make it impossible to put down. It shines a spotlight on a long-neglected episode in Czech history, and exposes the devastating effects of social cycles that operate on the premise of collective guilt, which sanctions crimes against a population based solely on ethnicity. As these cycles are being perpetuated even today, the issues Tučková explores are of global relevance.

–Véronique Firkusny

Jakuba Katalpa, Němci (Germans)

Host, 2012

A Czech émigré in London decides after her father’s death to seek out his German mother, Clara. Clara taught German in the Sudetenland during the war, but abandoned her son and returned to Germany, only sending him packages of sweets that make him hate her. Her Czech granddaughter travels to Germany only to discover that Clara is alive but suffering from dementia, unable to remember the past or to speak about it. Through Clara’s family, her history and that of the Sudetenland and the stories of various “Germans” unfurls.

Why translate it?

Němci won both the Czech Book Award and the Josef Škvorecký Prize. The Czechs’ history with the Germans is their most sensitive one, and too often tiptoed around with a finger to the lips. (Němci, the word for “Germans” in Czech, is derived from the word for “mute,” the book’s very title suggesting that silence.) Katalpa here focuses on the Sudetenland, the German name for the Czech border region that Hitler used as an excuse to occupy the Czech lands. In lucid language and short, telling chapters, Katalpa creates imaginative micro-narratives of characters, including Clara, living in the Sudetenland, challenging stereotypes of the Germans in the Czech lands before, during, and after World War II. Read an excerpt here.

–Michelle Woods

Radka Denemarková, Kobold (Kobold)

Host, 2011

Brutally honest, Kobold, nominated for two of the Czech Republic’s most prestigious literary awards, tells two loosely connected stories of women suffering male violence, a recurring theme in Radka Denemarková’s writing. In the first story, set in Nazi-occupied Prague, the violence is embodied by Michael Kobold, half-man and half-water goblin obsessed with the medieval Charles Bridge, who abuses his sensitive wife and reduces her to scribbling poetry on scraps of flour packaging. In the second story, a young unemployed Roma single mother is the victim of the newly prosperous, indifferent society of post-Communist Prague.

Why translate it?

Kobold is a powerful indictment of domestic violence and the totalitarian undercurrents that lurk within us all. Hard-hitting and poetic, the novel is a passionate condemnation of a society that renounces the less fortunate, pushing them to the margins as if they suffered from a contagious disease. Read an excerpt here.

–Julia Sherwood

Květa Legátová, Želary

Paseka, 2001

The collection includes several interconnected short stories about life in Želary, a fictional village in the Beskid Mountains, between the wars. The tough, tragic fates of the main figures, often corrupted by poverty and little experience, are described in a naturalistic yet poetic way. At one point, the small village community, clinging to ideas based on obsolete stereotypes and the cycle of religious and secular events, surprisingly turns to uncompromising evil, and cruelty.

Why translate it?

Květa Legátová (born Věra Hofmanová, 1919–2012) based her short stories on her experiences from an area of Moravia where she worked as a teacher in the 1950s. Želary was a Czech literary sensation, awarded the State Prize for Literature in 2002 and translated into five languages. It also gave name to the successful feature film (2003) based on Jozova Hanule (Joza’s Hanule), a novella which can be read as the final story of the collection.

–Sylva Ficová

Petra Soukupová, Zmizet (Disappear)

Host, 2009

Joining these three-books-in-one is the theme of disappearance or loss—of someone, or something, from a family: a brother, a father; part of a leg; patience, love, trust. Kids, front and center here, put their heads down and grind their way through life, while parents, blindsided by pain, barely notice. Siblings compete for attention—and toys—and are not often nice to each other. Soukupová’s strength comes largely from her letting characters describe, in their own words, the hurt they see in others, instead of having an omniscient narrator explain. The style, compact and condensed, gets across in five or ten words what others need paragraphs to convey.

Why translate it?

Soukupová, at 35, has already four books to her name (three adult, one children’s) and—unique to her generation in Czech literature—experience writing for TV, too. Zmizet received the country’s most heralded award, the Magnesia Litera Book of the Year, and its children’s-eye view of families, rare in much of what we read from Europe, is fresh and touching.

–Alex Zucker

Alexandra Berková, Temná láska (Dark Love)

Petrov, 2000

Dark Love recounts the narrator’s attempt to work through an abusive marriage and childhood in an allegorical conversation with a psychoanalyst. Drawing on everything from fairy tales and Dante’s Inferno to TV ads and self-help manuals, the novella showcases Berková’s experimental style in a feminist, absurdist reworking of the happily-ever-after myth. True to its title, the novella’s content is dark and disturbing, heavy with psychological and physical abuse. Yet Berková’s book is also darkly humorous: sly, parodic, and self-deprecating.

Why translate it?

Attesting to her centrality in the post-Communist Czech canon, Berková is the only author to appear in all four of the English-language anthologies of Czech fiction published since 1989, yet none of her books has yet been published in English translation in full. Read an excerpt here.

–Corine Tachtiris

Zuzana Brabcová, Stropy (Ceilings)

Druhé město, 2012

Winner of the 2013 Magnesia Litera prize for fiction, this partly autobiographical novel tells the story of Ema Černá, a middle-aged divorcée, who has to undergo psychiatric treatment. In the hospital, she meets women suffering from various kinds of addiction, and grapples with her own vivid memories, hallucinations, dreams and the harsh reality. The ceiling of her hospital room becomes a metaphor of her desire for freedom, a screen onto which the past and present, and fantasies and reality are projected, interweaved.

Why translate it?

Stropy will introduce Anglophone readers to the work of Zuzana Brabcová (1959–2015), a highly original and acclaimed writer whose searingly honest and poetic narratives have left an indelible mark on Czech literature. Stropy, her penultimate book, is a forceful narrative with a sophisticated structure reflecting the reality and atmosphere of a mental hospital and an imaginative exploration of human in/capacity.

–Sylva Ficová

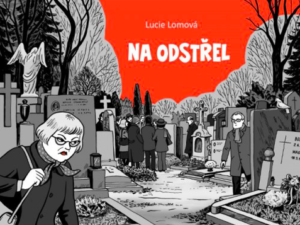

Lucie Lomová, Na odstřel (Knock ’Em Dead)

Labyrint Komiks, 2014

The play ended with a bang. The gun was supposed to be a prop. Was it suicide, murder, or just a mistake? Policeman Mr. Oulibský went to opening night instead of his theater critic wife, Dita, who stayed home with a fever. Now it’s his job to solve the crime, and all of the actors are suspect. Lomová, who lived in Chicago a year in the late 1960s, has both studied and worked in the theater. This clean-lined, cinematic strip in black, white, and gray, according to her, is more “comic crime” than “crime comic.” She also draws for children, and her comics have appeared in Aargh! and Stripburger. Éditions de L’An 2/Actes Sud has published all three of her graphic novels in France: Anna chce skočit (Anna en cavale), Divoši (Les Sauvages), and Na odstřel (Sortie des artistes).

Why translate it?

Comics’ and graphic novels’ star is rising in translation. The time is ripe for presses that, until now, have been translation-shy to find new authors and reach new readers. Lomová is the most popular Czech comics author abroad, thanks to prize-winning translations of her works in France, where the form has a devoted following.

–Alex Zucker

Sylvie Richterová, Slabikář otcovského jazyka (A Primer of the Father Tongue)

Atlantis, 1991

Three shorter prose works (Returns and Other Losses, Topography, and the title piece, A Primer of the Father Tongue) comprise this intriguing fragmentary, rhythmic, self-referential prose. Through a highly self-conscious first-person female narrator, vivid childhood memories of life in Communist Czechoslovakia, conveyed with abundant ironic humor, are confronted with a mature consciousness, reflecting the narrator’s adult life in Italy. A complex collage-like structure contributes to the blurring of boundaries between the comic and the tragic.

Why translate it?

Richterová explores the eternal questions of family, gender, history, home, and national identity in a captivating and thought-provoking style.

–Elena Sokol