This was the summer they entered phone booths and ran out shrieking. They were ten, flat-chested in bathing suits. Secrets smooth as sea glass. Limbs wrung like seaweed. They crowded into payphones, sweat-sticky and iridescent with sunscreen.

No one could say where the number came from. It seemed to them that one day it just appeared—a line thrown across some unfathomable breach.

You’ve reached 1-800-FAT-GIRL. We’ve got plenty of girls to go all

the way around. So pull it out and stick it in. Your credit card, that is.

Each time it was the same: they ran from the phone booth shrieking, gasping from laughter.

The fat girl’s voice was watery and strange. The oldest heard an echo. The youngest, a ghost. The quietest said it was like a seashell, the ocean rolling in your ear.

Where did the fat girls live? A basement, someone said. A cave. Maybe in a cave made of fat.

How could a cave be made of fat?

It would be all gloopy. Like one big waterbed.

The fat girls slept on waterbeds—this was the one thing on which they all agreed.

Days, they tanned in front yards. They draped themselves across towels, eyes low and watchful, darting like bees.

They tanned. They chanted. They stole the baseball caps of boys.

They were shameless. They were bored.

What do the fat girls do if nobody calls? They just sit around. Eat jelly from the jar.

Time’s different there. It doesn’t move except when someone calls.

At night, the fat girl’s voice followed them. It hummed nothing songs. Sat around leafing through their older sisters’ magazines. When their parents fought, it snuck outside, kept them company on the swings. Even in the dark, you knew it was always there—an ocean rolling toward infinity.

They watched. They whispered. They grew their secrets like pearls. At night, they dreamt their houses were on fire. Dream air pinned them down.

Their secrets changed, then changed again. They parsed the world for hidden clues: song lyrics, radio ads, the passing comments of neighbors. She’ll be a looker when she grows up.

They looked. They whispered. They threw themselves at each other’s older brothers. At night, they burned up in secret flames.

Years passed. Their fathers blushed and turned away. Their mothers lay passed out on the couch. Their older sisters became black holes, perpetual disappearances in the night.

They still threw themselves at each other’s older brothers, but only when no one was looking, only in the dark. They became ascetics, eating nothing. They became ravenous, eating everything. They didn’t remember the fat girl. Their eyes lost their sting.

It was the youngest who heard it again, one night wandering sleepless through her house. She’d woken from a dream of eating everying inside the refrigerator, and she moved through the dark hall, panicked, to see if it was true. When she saw that it wasn’t, she stood still for a minute, transfixed by the glow of the open door as though waiting for a sign.

At school the next day, the others stared at her blankly.

Heard what? they asked.

The voice. The fat girl. They shook their heads. Remember? The payphone?

They blushed and turned away. It was like stumbling upon evidence of a self they’d long since disavowed. They didn’t like to be reminded.

But that night, the voice pricked them each awake. When they finally drifted uneasily into sleep, it dripped like a leaky faucet through their dreams.

They endured the school day, then assembled wordlessly in the hall. They looked at each other and gave slow nods.

That night, in the phone booth, it was the youngest who dialed, squinting at the numbers on her mother’s credit card. The others held their breath, leaned in close.

Yeah? The voice sounded tired, like they’d disturbed her from sleep.

Hi, said the oldest, louder than she meant to. A pause.

You girls, the fat girl said finally. You used to call and run away shrieking.

They blushed in the dark. So what if it was us?

So nothing. I liked you better then, is all. I got to sit around all day on the waterbed, eat jelly from the jar. Now it’s a new operator, new rules. The fat girl sighed like they couldn’t understand.

So what do you do now?

That’s the problem: it’s like floating around a black hole. Or like being one. Everything goes into you and nothing sticks. A story running backward till you’re nothing at all.

When they called again the next night and the next, the fat girl laughed. Knew you’d be back, she said.

They became insomniacs, sliding around all directions of the night. Everywhere they went, the fat girl’s voice followed, sweet and terrible as a lullaby.

Tell us more about how it used to be. Used to be when?

When we used to call.

Well, there was a cave, for one thing. And I could hear the ocean, for another. Doesn’t that sound lovely?

Yes, they agreed. Lovely.

And I had a whole necklace full of pearls. Each one used to sing to me in the night.

At school, they never spoke of the fat girl. Days were hard and full of edges. At night, they became formless, fleshless. The dark opened like a valve.

Sometimes the voice dared them: You could burn this house down, it said. You could.

The nights grew wide, and they wandered, sleepless. They swallowed pills, lied about their ages. Climbed in and out of the backs of cars. They watched from someplace outside their bodies as dream air pinned them down. Sometimes they had the feeling this was a story they’d heard already, that the fat girl had always been there, narrating in their ears.

A story moving backward. In which case, the fathers they remembered would soon return. Their mothers would startle awake. Their sisters would emerge from the backs of cars, unvanished from the dark. The nights would grow smaller and opaque with sleep— tiny as pearls, closing back inside the heart.

They themselves would grow younger. They’d grow sure and true—limbs wrung like seaweed, secrets smooth as sea glass. It would be like running toward the ocean at night: you couldn’t see it, but you knew it was there. Relics and sea life beneath the waves.

Or they’d emerge: fleshless, formless, their hearts flung open.

Pearls everywhere, spangled like stars.

__________________________________

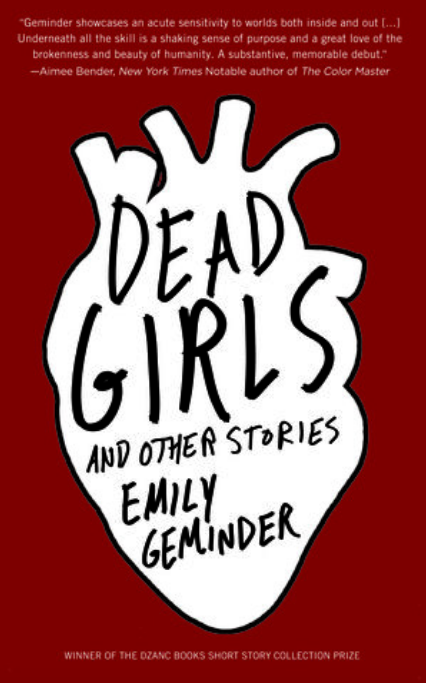

From Dead Girls and Other Stories. Used with permission of Dzanc Books. “1-800-FAT-GIRL” originally appeared in American Short Fiction. Copyright © 2017 by Emily Geminder.