Why Spiritualism Persists in our Fictions and Culture

In the Face of Cynicism, Believing Can be a Radical Act

An article every bit as strange as fiction ran in April’s New York Times.

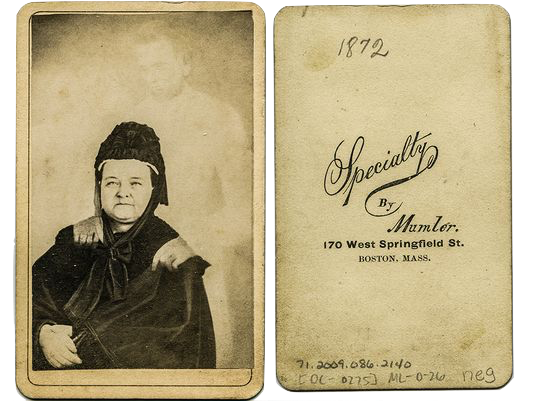

Titled “A Dead Child, A Ghostly Photo and A Mother Charged with Murder,” the article told the story of a Pennsylvania photographer, Sunny Jo, commissioned via Facebook by a North Carolina woman named Jean K. Ditty to manufacture a spirit photograph of her recently deceased 2-year-old daughter, Macy. Spirit photography, in case you don’t know, was a subset of the 19th-century social and religious phenomenon known as Spiritualism, in which the bereaved employed mediums and ghost-seers to contact their dead loved ones via séances, trance-speaking, mesmerism, automatic writing and, in some cases, wet-plate photography (an image of the sitter would be double-exposed with an image of the deceased or someone approximate to them, then given as proof that the ghost had been captured).

Albeit in some varied form, these practices persist today.

Sunny Jo—who offers a digital spirit photography service called “One More Time” to the families of the deceased—did much of the photographic work commissioned by Ditty pro bono only to learn later that Ditty and her boyfriend Zachary Keefer had been brought up on charges of first-degree murder and felony child abuse in the beating-death of Macy. Between commissioning the photo from Jo and being indicted, however, Ditty had shared the photo widely on social media. Jo soon began receiving excoriating messages from the public—what he described as “a lot of hate” for his seeming complicity in the murder of a 2-year-old girl.

The photo itself shows a turbaned Jeanie Ditty sprawled in a cemetery before a headstone decked with flowers; little Macy stands behind her in an aura of light, her ghost-hand on her mother’s shoulder.

A hybrid of true crime, weird fiction, and domestic realism, the story of Jo, Dittie, and little Macy is telling of Spiritualism’s ambiguous standing in our present cultural moment. On the one hand, the story illustrates the Spiritualist movement’s chief dichotomy between trickery and sincerity. In Spiritualism’s Golden Age (approximately 1840-1920), whether or not most mourners knew it, they were often being swindled by the mediums they hired, never mind that the solace they gained in the bargain was nothing if not genuine.

On the other hand, however, the story also reverses this dynamic. Jo, the so-called “medium,” was swindled by the mourner, Ditty. It’s an ironic posture that seems borne of fiction, but happens to be all too true. And it poses a question about Spiritualism, which is consistently all over the stories we tell—of yesteryear and of today: The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1852), The Bostonians by Henry James (1886), Nightmare Alley by William Lindsey Gresham (1946), Affinity by Sarah Waters (1999), Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel (2005), C by Tom McCarthy (2010), The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton (2013), The Vanishers by Heidi Julavits and Mr Splitfoot by Samantha Hunt (2016), among many others.

We’re post-Fox Sisters, post-Madam Blavatsky and post-Miss Cleo, in a new, terrifying and Trumpian age, where nothing is private and few can be fooled—where faith, in anything, is waning—and yet Spiritualism persists in our fictions, persists in our culture. Its spirit is strong.

What uncommon truths might it tell, if we let it?

* * *

Though the historical tenets of Spiritualism reach as far back as the 18th-century in the writings of Anton Mesmer and Emmanuel Swedenborg, modern Spiritualism as we know it today came about in a very specific time and place: 1847 in Hydesville, New York. Here, the two youngest daughters of a Methodist family, Katherine and Margaret Fox, heard a strange rapping noise in the room that they shared, untethered to any immediate source. After further scrutinizing and replicating the sound by snapping their fingers, the Fox sisters proclaimed to a host of adults that a peddler had been murdered in the cottage years ago. The girls ascribed the rapping sound to the peddler’s attempts to communicate with them, revealing how and why he died. Upon the adults digging under the cellar, they found a little nest of bones.

The Fox sisters’ talents expanded from there.

Throughout the mid-to-late 19th century, they toured the major cities of the northeast spreading, if not the religious gospel of Spiritualism, then at least the widespread conviction that the living could communicate with the dead. After the lanterns were lit, the seekers’ hands joined (what Spiritualists called “the telegraph of souls”) and the medium had “tested the batteries” by rapping a few times to conjure the spirits, whoever at the séance who had sought those spirits’ counsel would be privy, through the medium, to messages like this: “It is very delightful to be put in communication with those we love. All is well with me, my dear. There are new developments being made to the world, and all, from the least to the greatest, shall know the truth.”

It was those of a more mystical bent, like the lay scientist-philosopher Andrew Jackson Davis (aka: “the Seer of Poughkeepsie”), who, concurrent to the rise of the Fox Sisters and other so-called “mediums,” turned Spiritualism into faith. Jackson Davis synthesized a widespread belief in the “night-side of nature” with the mesmeric and animal magnetism-principles of his forebears to create a popular fringe religion that took certain sects of America and Britain by storm over the course of the next 80 years.

Interestingly, Spiritualism as a social movement was also bound up with an agenda of left-wing reform that, in the context of its own day and age, would’ve made Bernie Sanders look like Newt Gingrich. Women’s rights, abolition, dress reform, temperance and, in some cases, health cures and polyamory were all part of the Spiritualist platform to varying degrees, especially among middle and upper class New Englanders. Performative offshoots of mediumism such as spiritualist orchestral arrangements, painting and photography were all general by the start of the Civil War in the early 1860s; the latter discipline, pioneered by Boston confidence man extraordinaire, William H. Mumler—and continued by Sunny Jo in 2016—boasts an 1869 photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln in which the ghost of the late president hovers protectively over her, his hands resting upon her shoulders.

Mary Todd wasn’t the only notable American or Brit of a literary persuasion to throw herself on the emotional mercies of Spiritualism. William Lloyd Garrison, Horace Greeley, Victoria Woodhull, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and William James were all drinking the Kool-Aid, too.

When the Fox Sisters admitted publicly in 1888 that the rapping of the murdered peddler was really the thumping of apples they had tied to puppeted strings, Spiritualism underwent a sort of death. The following year, a billboard in Rochester, NY proclaimed the following: “MODERN SPIRITUALISM—BORN MARCH 31, 1848—DIED AT ROCHESTER, NOVEMBER 15, 1888. AGED 40 YEARS, 7 MONTHS AND 15 DAYS—BORN OF MISCHIEF, AND GONE TO MISCHIEF.”

* * *

But the movement, much like the deceased it claimed to reveal, wouldn’t die. And it went on for another three decades…

It drifts among us still today in the form of crystal healers, aura photographers, palm readers, and drop-in psychics. Sunny Jo (medium) and Jeanie Ditty (seeker) are two of its children, their dynamic deformed and perverted by time. Spiritualism is all over today’s literature and the literature, too, of its own golden age, reflecting the culture that harbored and fed it, reflecting our culture, today, which still does.

Happily for literature, Spiritualism has dynamite trappings.

* * *

Some of the earliest novels to prominently feature Spiritualism were also the most mistrustful of it. To some degree, this makes good sense; they were written at a time when Spiritualism was in vogue.

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1852) takes place in the utopian community of Blithedale in the mid-1800s, which was thought by many to be a thinly veiled depiction of Brook Farm, a Transcendentalism-inspired agrarian living experiment launched by a former Unitarian minister and his wife in Massachusetts in 1841, and sustained by 19th-century personages such as Margaret Fuller and Hawthorne himself, who was a founding member.

A treatise on the pitfalls of idealism and the dubious exaltations of human entanglement, The Blithedale Romance introduces the Spiritualist element in the form of the legend of the “Veiled Lady,” delivered round-the-campfire-style to protagonist Miles Cloverdale in the novel’s opening pages; the legend relates the story of a popular clairvoyant who evaporates from the social scene she holds under her sway. Thus does the “Veiled Lady” come to hover omen-like over not only the narrative itself, but also the increasingly unwieldy aspirations of Blithedale, an Eden on the razor’s edge, forever threatening to backslide into passive superstition. Spoiler alert: the utopia fails. In due course, the “Veiled Lady” is revealed not only to be actual but to have been hiding in plain sight all along as one of Blithedale’s bosom members. The novel juxtaposes the duplicity and stagecraft of Spiritualism, coming into fad when it was written, with the doomed naivete of utopian ideals, though not without a hint of mystery. Even when the “Veiled Lady,” at last, is unveiled, her power lingers on the scene, like a spirit emanation or a fog of dry ice.

Henry James’s The Bostonians (1886), the other major 19th-century novel preoccupied with Spiritualism, examines the movement through a far less, shall we say, romantic lens than The Blithedale Romance. This might’ve been partially due to the fact that Spiritualism in the 1880s was on the run from a hyper-rational army of debunkers; interestingly and tellingly, perhaps, James’s brother, psychologist and philosopher William James, was not among them, and even went so far as to sit several times for celebrity medium Leonora Piper before establishing the American Society for Psychical Research in 1884.

The Bostonians, published in serial by James in Century Magazine, centers on an amorous constellation of individuals attempting to navigate the Boston Brahmin reformist culture of late 19th-century New England, in which Spiritualism was a crucial, if often utilitarian element. The Spiritualist in James’s novel is Verena Tarrant, a fetching young trance-speaker given over to the influence of her mercenary quack father, Dr. Selah Tarrant. Soon enough, Selah meets with competition for the soul of his daughter in the form of Olive Chancellor, a dour and acerbic suffragette who, in coded 19th-century fashion, has feelings for Verena that extend beyond mere collegiality. The ensuing struggle over Verena—further complicated by the arrival of Basil Ransom, a Mississippi social conservative and Olive’s cousin—embodies a very particular brand of Spiritualist scuffling between 19th-century feminists, on the one hand, who sought to use Spiritualism as a tool to enshrine the ascendancy of women in the public sphere, and mediums, on the other, who were in it for the lucre.

Although it’s often labeled a comedy, The Bostonians is actually very depressing: nobody, remotely, obtains what they want, except the cis white male. At the end of the novel Verena Tarrant, betrothed to mansplaining frat-bro Basil Ransom, is “wrenched” bodily from a lecture hall, the site of her former empowerment, in tears, while Olive rushes after her. These tears of Verena’s, James writes in the novel’s final moments, “were not the last she was destined to shed.”

Applying a proto-dirty realism to a dubious historical milieu where things were rarely what they seemed, The Bostonians endeavors a cynical send-up of Spiritualism, as though priming America, two years later, for the downfall of the Foxes, when the movement showed its seams.

William Lindsay Gresham doubles down on James’s cynicism in The Bostonians with the mid-20th-century nihilism of Nightmare Alley, to which Michael Dirda ascribed a “Dostoyevskian power,” “[chronicling] a truly horrifying descent into the abyss.” Dirda also compared it to Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, which is not altogether off-target.

Nightmare Alley charts the rise and fall of attractive sociopath Stan Carlisle, a dimestore magician who hopes to make it as a carnival “geek” and washes up in the South to take his place among a gallery of physical and psychological grotesques including Sailor Martin, Major Mosquito, Bruno and Mamzelle Electra. After conning mind-fuck techniques out of fortuneteller Zeena, Stan moves on to the big-time in Manhattan, where he reinvents himself as the Great Stanton, a medium-cum-evangelist-preacher of the spiritualism-derived the Church of the Heavenly Message. (If you’re picking up on a Flannery O’Connor vibe in all this—like, say, Hazel Motes from Wise Blood—you’re onto something, especially in that O’Connor, too, had read Miss Lonelyhearts and admired West’s spiritual intensity and moral dubiousness.) When the Great Stanton happens upon the mark whom he believes will make his career, business tycoon Ezra Grindle, what’s already unseemly turns downright depraved.

Bad vibes become annihilation.

Ironically Gresham, who lived a life as messed-up in many ways as his antagonist Stan, is widely remembered for just one other book, Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls (1970), a biography. Ironic, because the magician and escape artist laser-focused a portion of his career on debunking mediums and psychics who, much like P.T. Barnum nearly 50 years before, Houdini perceived as inferior show-men and women. Yet Gresham’s novel, while secure in its conviction that Spiritualism is fraudulent, ascribes a great, entropic power to Spiritualists themselves: exploiters of the vulnerable, corruptors of the strong, re-fashioners of scoundrels into reprobate gods. In Nightmare Alley, Spiritualism provides an outlet for humankind’s innate degeneracy, culling from darkness what’s already there.

Something similar happens in Sarah Waters’s novel Affinity (2000), about an upper-class depressive turned to charity work who falls under the spell of a Spiritualist imprisoned for fraud and assault inside gloomy Milbank Prison. The only difference being this: Waters’s novel is one of the first in all those featuring Spiritualism to hinge noticeably on the tension of whether or not Spiritualism is, in fact, fake. Narrated by way of alternating diary entries from the depressive, Margaret, and the Spiritualist, Selina—a quality that underscores the novel’s tightrope subjectivity—Affinity uses simple suspense (is it real or not real?) to reap massive rewards. Add to that the rather one-sided love-that-dare-not-speak-its-name between Margaret and Selina, cultivating itself during circumscribed visiting hours in the dank cold of the prison, and you have a novel that freshens the intellectualism of Hawthorne and James, and the Gothic fatalism of Gresham with a compelling mystery/romance plot.

Can Selina or can’t she commune with the dead?

Is she guilty or not of the crime that they say?

When a lock of Selina’s hair manifests one night on Margaret’s pillow she for one is convinced that Selina “had sent it to me, from her dark place, across the city, across the night.”

As in Nightmare Alley and to some extent The Bostonians, the descent into pure human cruelty is there, but never in the way you’d think. Indeed, Affinity’s retrofitting of the Spiritualist conceit with the menacing romance of Hawthorne, or even someone like Poe—who applied his gruesome critical intelligence to 19th-century Mesmerist practices in his story “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”—has become all but a trope in the Spiritualism-centered novels that followed it. (A similar complication and re-romancing of humankind’s inhumanity can be found in Robert Eggers’s 2015 film The Witch, in which the threat is human, sure, but also there are lots of witches.)

The dead in Affinity are more than a sham.

Sometimes, as it happens, they’re also the living.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black (2005), a genuinely supernatural yet also dead-serious (and often quite funny) novel of Spiritualism in present-day England. Mantel, best known for her Thomas Cromwell-trilogy in the offing which garnered her two Booker Prizes in the space of three years, anchors her narrative with an unforgettable protagonist: Alison—an obese, perfume-redolent medium who caters to the spiritual seekers of London’s outer suburbs. Talented and longsuffering, Alison sees and hears the dead on a massive, unrelenting scale. Here, Mantel brilliantly subverts the literary and actual history of Spiritualism on two successive levels: Alison’s dead are not only real to her, other characters and, gradually, the reader, they are nattering, vulgar, mendacious, aggressive—everything, pretty much, Spiritualism insists they aren’t.

Alison’s “spirit guide” through the great beyond, Morris, is a louche, smelly pervert “in a book-maker’s check jacket and suede shoes with bald toecaps”; he is frequently slumped in Alison’s bedroom, threatening to touch himself. Unfortunately (and heartbreakingly) for Alison, Morris rolls deep, accompanied through the after-life by a host of abusers and thieves who, when they lived, tormented and raped Alison in her girlhood. If Beyond Black sounds like it will ruin your life, know that Mantel offsets its punishing bleakness with the gay irreverence of the novel’s milieu: the blue-haired psychic crystal-gazers, dripping with turquoise, who haunt London’s suburbs.

“Travelling: the dank oily days after Christmas,” Mantel writes in the novel’s opening passage. “The motorway, its wastes looping London: the margin’s scrub grass flaring orange in the lights, and the leaves of the poisoned shrubs striped yellow-green like a cantaloupe melon.”

Where The Blithedale Romance and The Bostonians are skeptical of Spiritualism, and Nightmare Alley and Affinity invest the movement with a dark, Machiavellian ingenuity, Beyond Black, smartly, toes the line. In Alison’s universe, Spiritualism comes as somewhat of a revelation.

Also, somewhat of an out and out fraud.

However, it’s Beyond Black’s winningly persistent romanticization of Spiritualism and the actual possibility of the supernatural that distinguish it. The same could be said of the spate of Spiritualist novels or novels involving Spiritualism that have followed Mantel’s in recent years: C by Tom McCarthy (2010), Swamplandia! by Karen Russell (2011), The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton (2013), The Vanishers by Heidi Julavits and, most recently, Mr Splitfoot by Samantha Hunt (2016). One could chalk this up to what so many in the literary community have been calling the New Fabulism—or, as I privately like to refer to it, the New Romanticism. But whether Spiritualism is actual or imagined in these novels isn’t the point; in every one of them, the dead possess power.

And it’s only real power the living believe in.

* * *

When Sunny Jo manufactured a spirit photograph of young Macy for her mother Jeanie Ditty , he didn’t know Ditty had murdered her daughter. He couldn’t have known. He believed in her loss.

And believed, in spite of his pictures’ fakeness, he was helping a mother to feel something real: the meaningful reversal of a meaningless absence.

“To me,” Jo said, post Ditty’s indictment, “she seemed like a grieving mother.”

Whatever Ditty’s motives in hiring Jo—to divert suspicion from her and her boyfriend, to cosmically absolve herself—it stands as a monstrously cynical act. More than that, it’s anti-human, superseded only by the murder itself.

Jo’s motives, on the other hand, for making the picture for Ditty for free are so human it hurts the heart. Perhaps an act of vaudeville, but nonetheless an act of faith.

Because the principles of Spiritualism are valid, necessary. The solace we seek from Spiritualists—through speaking, seeing, hearing, touch—in one form or another, they often provide us, whether or not their assertions are false and whether or not we commit them a fee.

In this era of Trump and the Panama Papers, as America teeters at peak cynicism, peak darkness just around the bend, it’s important, of course, to maintain skepticism, to keep calling, “Bullshit,” to state: “I am leery.”

The historical alternative to this is unthinkable.

The temptation is there to embrace cynicism toward any one candidate, movement, or cause. With so many Jeanie Ditty’s here in our midst, what need have we for Sunny Jo’s?

But believing can be the more radical act, in spite of all we know and fear.

If we are wrong and we are fools, at least we’ll have believed in something.

Adrian Van Young’s latest novel, Shadows in Summerland, is available now.

Adrian Van Young

Adrian Van Young is the author of Shadows in Summerland and The Man Who Noticed Everything. He lives in New Orleans.