Bob Shacochis: How Surfing Lead Me to Writing

On a Pathological Love of the Hardest Sport in the World

Kiribati, Christmas Island, erstwhile thermonuclear playground in the South Pacific, two years ago and counting. Neither the beginning nor the end of a journey toward the lightness of being but, for me, more of the same, surfwise, selfwise, further evidence of the truth inherent in the mocking axiom, You should have been here yesterday. Yesterday, in fact, is the stale cake of many an aging surfer like myself. Yesterday is what I walked away from, determined to someday again lick the frosting from the sea-blue bowl.

Out there on the Kiribati atoll, we were a small, neoprene-booted family of elite silverbacks—Micky Muñoz, Yvon Chouinard, Chip Post—and brazen cubs—Yvon’s son and daughter and her boyfriend; Chip’s son. Micky (61) was the first maniac to surf Waiamea Bay. Yvon (60), the founder of Patagonia, legendary rock and ice climber, had surfed just about every break in the world, starting with Malibu in 1954. Chip (60), a lawyer in LA, had seniority in almost every lineup from Baja to San Francisco. The second generation Xers were already dismantling breaks all over the planet. In years (middle), condition (not splendid), experience (moderate), and ability (rusted), I was the odd water monkey in the clan, neither out nor in, and the only one dragging an existential crisis to the beach. The only one who had opted out of The Life, the juice. Maybe I wanted back in, but maybe not. I felt like an amputee contemplating the return of his legs but long accustomed to the stumps.

In the coral rubble of the point at the channel mouth, we stood brooding, muttering, arms crossed on our collective chests, trying to conjure what was not there. The trade winds had developed spinning disease. The glorious, mythical break had been crosswired by La Niña, chilling the equatorial water and deforming the shoulder-high waves, which advanced across the reef erratically, convulsed with spasms, peaking and sputtering inconclusively, closing prematurely, like grand ideas that never quite take shape or cohere to meaning. In years past at this same spot, Yvon and his company of “dirtbaggers” had been graced with an endless supply of standard Christmas Island beauties—precise double-overhead rights, shining high-pocketed barrel tubes that spit you out into the postcoital calm of the main harbor. This time, however, we had traveled far from Oceania’s interpretation of Euclidean geometry and we got this, bad poetry, illiterate verse.

Yeah, well . . . this was a hungry crew, and you never know what’s inedible until you put it in your mouth. The Xers flung themselves into the channel; the rip ferried them down the pass and out to the reef. Chip goes. Then Yvon, but less enthusiastically. “I’m not going,” said Micky, squatting on his heels. I sat too, thunderstruck with relief. Forget that it had been more than seven or eight years since I surfed, or almost fifteen since I surfed steady, daily, with the seriousness and joy of a suntanned dervish. With or without its perfect waves aligned off the point, one thing about this break on Kiribati horrified me. As a swell approached the reef and gathered its peak, the trough began to boil in two sections vital to the fall line of the wave. When the wall steepened to its full height, thinning to emerald translucence, the two boils morphed into thick fenceposts of coral embedded in the wave.

We watched Yvon muscle onto an unreliable peak, gnarled and hurried by the onshore wind. The drop was clean, exhilarating, but without potential. He trimmed and surged past the first spike of coral, the fins of his board visible only a few scant inches above the crown. Then the wave sectioned and crumbled over the second spike. Without a bigger swell and an offshore wind, it was going to be like that. Yvon exited and paddled in.

“Those coral heads really spook me,” I confessed.

Yeah, well. Some risks you fancy, some you don’t. When more water piled up, they weren’t much of a problem, Yvon assured me. The stay-alive technique was, fall flat on your belly when you left your board. Glide shallow, protect your head, avoid disembowelment or the tearing off of your balls. Solid advice.

“Yeah, I guess,” I said. For a half hour, we watched the rodeo out on the reef, Chip and the Xers rocketing out of the chute, tossed and bucked into the slop. Their rides resembled a five-second saber dance with a turquoise bull, something like that. Micky kept looking up the coast, across the scoop of bay to where the shoreline straightened out in front of a reef I had named, ingloriously, Caca’s, because the locals in the nearby village mined the beach with their morning turds. The tide had begun to ebb.

“Caca’s going off!” Micky cheered. Yvon and I squinted at the froth zippering in the distance.

“Yeah?” we said, unconvinced, but off we trudged to check it out.

* * * *

So.

There is a pathology to my romance with surfing that contains a malarial rhythm; its recurrence can catch me unaware, knock the wind out of my metaphysical sails, bring fevers. For a day or two I’ll wonder what’s wrong with me, and then, of course, I’ll know.

I would like to tell you that I remain a surfer but that would mostly be a lie, even though I grew up surfing, changed my life for surfing, lived and breathed and exhaled surfing for many years. Now I can barely address the subject without feeling that I’ve swallowed bitter medicine, I avoid surf shops with the same furtiveness that I steer clear of underage girls, and I wouldn’t dare open up a surf magazine and flip through its exquisite pornography of waves, unless I had it in mind to make myself miserable with desire. In any pure sport, in any art or extreme passion, such disengagement happens sooner or later to all but a blessed few to which the alternatives never quite make sense.

My life only started when I became infected with surfing, moon sick with surfing, a 14-year-old East Coast gremmie with his first board, a Greg Noll slab of lumber, begging my older brothers for a ride to Ocean City, two hours away if you drove at 90 miles an hour, which they did. Before that, I was just some kid form of animated protoplasm, my amphibian brain stem unconnected from any encompassing reality, skateboarding around suburbia like an orphan, ready to be adopted and subverted by the Beach Boys, who can still make me swoon when I hear “Surfer Girl” on the radio.

I remember in high school the spraying rapture of the first time I got wrapped—seriously, profoundly, amniotically wrapped—by an overhead tube, an extended moment when all the pistons of the universe seemed to fire for the sole purpose of my introduction to the sublime. This was at Frisco Beach, south of the cape on Hatteras. I remember the hard vertical slash of the drop, the gravitational punch of the bottom turn, and that divine sense of inevitability that comes from trimming up to find yourself in the pocket hammered into a long beautiful cliffside of feathering water. It only got better. There pinned on the wall in front of me, entirely unexpected and smack in my face, was a magnificent wahine ass-valentine, tucked into a papery yellow bikini and, since I didn’t know anyone else had made the wave, for a moment I thought I was experiencing a puberty-triggered hallucination, but there she was in the flesh, slick and glistening, whoever she was, wet as my dreams, locked on a line about two feet above me, crouched in what is known in the animal kingdom as the display position. Surgasm—can that be a word? You have to understand, I was 16 and, up to that point, a pioneer of the wonderful world of geeks. The wave vaulted above us and came down as neat and transparent as glass and we were suspended and bottled in brilliant motion, in the racing sea, and friends, that ride never ended, unto this day.

Boy, girl, wave—whew. On earth, I could ask no greater reward from heaven nor define any other cosmology as complete as this. Point, click, put it in your shopping cart. When you’re given something good and true you want to stick with it, but it’s exactly here, at the impact zone of commitment, that a problem arises. Let the master speak to this.

“I think the biggest lesson I got out of surfing,” Yvon told me one night on Kiribati, “is that if you want to take it seriously, you’ve got to completely restructure your life so that at any moment you can drop anything and go surfing. At Patagonia [headquarters in Ventura], we have a Let My People Go surfing policy written into my employees’ contract. You can’t underestimate what that means—I don’t mean as a business, but as a life. A lot of people end up on the fringes because they’re not accommodated by their employers. And it gives you something to look forward to—maybe the surf will be up tomorrow. Tennis is a game, but surfing is a real passion. It’s not something you just do when you’re young, it’s something you do your whole life. I think surfing was the first counterculture, absolutely the first one.”

It’s a passion, sure, yet like all of the best pursuits and fine indulgences a privilege, requiring generosity from above. Luck. The liberating paradox of obsession. At the very least, a parking place on the overcrowded, overregulated, dog-hating coast.

Most upstanding civilians I know have trouble believing this, but surfing was the energy that formed my identity when I had no other; it was my coming-of-age narrative. Surfing sculpted my ambition, surfing gave me an appetite for the wild world, taught me a value system and the virtues of nature, taught me (through the innovative prose of Surfer magazine) to be word-drunk, intoxicated with new language, and prepared me, ultimately, to be free, by making me practice persistence and, as much as I could muster, courage. To set aside fear and paddle out on a day when the beach is lined with fire engines and littered with boards snapped in half by Godzilla waves. To paddle out blind with myopia and alone and lonely into unknown waters. To paddle back out after you’ve just been seized by an undertow, the strength of which you never imagined.

The first time I declared my irreversible independence and defied my father, it was to go surfing—I was an underage minor boarding an international flight to the West Indies. I joined the Peace Corps to go surfing in the Windward Islands. I moved my household from Iowa, where I was teaching at the university, to the Outer Banks to go surfing. I vividly remember spectacular waves on Long Island, New Jersey, Virginia Beach, North Carolina, Florida, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, the islands of the Caribbean, waves that when I kicked out, through the sizzle of the white water I could hear hoots of astonishment on the beach, which felt like your ecstasy was shouting back at you, and beyond you, to a future where one day you might recollect that once, for a time, you had been a great lover in your affair with the world. You weren’t just sniffing around.

But there are many ways to love the world. My sea became literature, my waves rolled into books, my rhythm became the pulse and flow of sentences, not swells. No regrets there, yet I found myself hunkered down on ocean-lonely prairies, striking a Faustian bargain with the gods of success. In my life as a surfer, it wasn’t time to move on, it was time to stay, but I couldn’t, being deranged by adulthood and its sober illusions. Years later, when the opportunity came up to fly to Kiribati with Muñoz and Chouinard, two of my boyhood idols, though I often daydreamed of riding waves, I just didn’t know if I wanted to surf again, to become reinfected with surfing, because I knew there was a chance I would stop living one life and start living another, that I would uproot everything and remake it according to a different sort of yearning, a different set of needs, and I didn’t particularly think that was possible. Yes, Bill Finnegan had done it, but no one else, as far as I knew. And as Chip once told me, and not incorrectly, “The greater human enterprise requires more than doing your own thing.”

Still, Micky designed me a new board, which Fletcher, Yvon’s son, shaped and glassed for me. Still, I flew 6,000 miles to Christmas Island, artificially mellowed by some kind of depresso’s drug to make me stop smoking. And I gulped back the dread that the point break had induced and walked down the beach with Micky and Yvon and Peter Pan, longing for some of that Old Blue Magic.

What we found there at the break in front of the village was surfing’s equivalent of a petting zoo—little giddyap waves, pony waves, knee-high and forgiving—and if these weren’t the waves we had come for, they were nevertheless the only waves we were going to get this trip. The silverbacks made every wave they wanted; I made maybe one out of five, my body aching to restore its balance and former grace. Micky and Yvon tutored my rehabilitation, offered comfort: “It’s not like getting back on a bicycle,” said Micky. “You spend thirty seconds on your feet a day as a beginner or intermediate. Try learning anything else at thirty-second-a-day intervals.” “It’s the most difficult sport there is,” added Yvon, the rock-climbing pioneer. “There’s no more difficult sport, absolutely. You have to be young to learn it. You can start snowboarding at 50 years old and get damn good at it. You can’t do that with surfing.”

Oftentimes when I pivoted my board landward to get in position, the fins would hook up in the reef. I felt clownish, hesitant, my judgment blurred by bad eyesight. But finally none of that mattered, finally I started hopping into the saddle, having fun. That I considered to be a mercy.

I had collided head-on with my youth and what needed resurrection, though not in the boomer sense of never letting go. I had let go. But the dialectic of my transformation had reached a standstill: Surf=No Surf=??? I wanted more waves. I wanted more waves the way a priest wants miracles, the desert more rain. Throughout the middle years of my celibacy, living a counterpoint life, I had prayed hard to be welcomed home again to waves, and these tame ponies on Christmas Island would, I hoped, serve as that invitation. I have since surfed San Onofre with limited success. Florida too, but only once. I have yet to find the right equation that will spring open my life, rearrange my freedoms, and let me throw my desire back into the sea. My resources are modest, my obligations many; my dreams are still the right dreams but veined with a fatty ambivalence. Maybe the season has passed, but I don’t think so. My two lives, and my two selves, have to do the Rodney King trick and learn to get along.

The thing about surfing, Chip told me, is that “you leave no trail.” Yes sir, Micky agreed: “It’s like music—you play it and it’s done.”

The strategy, though, that you’re looking for is the one that teaches you to hold the note.

(2001)

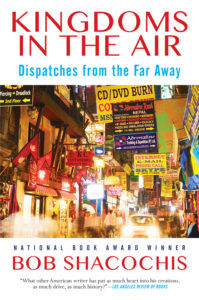

This essay originally appeared as “The Life I Didn’t Get” from KINGDOMS IN THE AIR. Used with permission of Grove Atlantic. Copyright 2016 by Bob Shacochis.