Why Are There So Many Novels About Famous Writers?

Heller McAlpin Analyzes a Recent Surge in Biographical Fiction

Write about what you know and care about most deeply, aspiring writers are repeatedly instructed. Well, what’s something writers know and love best? The books and authors that made them want to write their own.

Brace yourself for a bevy of novels about famous authors coming out this spring—historical fiction featuring characters ripped from the gold-embossed spines of great literature: George Eliot, Anton Chekhov, Samuel Beckett, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman and M.F.K. Fisher, to name a few. It sometimes seems that instead of trying to create their own memorable Elizabeth Bennets, Hester Prynnes, Ahabs, and Godots, writers are intent on figuring out how the hell their creators did it. And how better to submerse oneself in a beloved book than by channeling its author’s very identity and mindset?

Literature about famous authors is not a new thing. Dante’s Inferno featured Virgil. More recent standouts include The Last Station (1990), Jay Parini’s memorable portrait of Tolstoy at the end of his life; The Master of Petersburg (1994), J.M. Coetzee’s novel about Dostoyevsky; The Hours (1998), Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning homage to Virginia Woolf and Mrs. Dalloway; and The Master (2004), Colm Tóibín’s masterful ventriloquism of Henry James. There are also plenty of less stellar examples, with Jane Austen, William Shakespeare, Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway and his wives starring as perennial favorites.

What’s the attraction, and why so many now? Is it the hoped-for literary cachet of a famous name? Hero-worship? Escapism? The joy of literary sleuthing and research unfettered by the strict adherence to facts required for biographies?

Set in a distinctive wing of the gallery of historical fiction, these portraits refract the past through a contemporary lens, addressing issues with abiding relevance, such as the particular challenges faced by single women or gay men. While some are as lifeless as plaster busts, many others, like Dinitia Smith’s The Honeymoon, (due from Other Press in May), are the literary equivalent of biopics—engrossing, moving stories that provide a deeper understanding of the writers who penned our favorite books, but without the daunting heft of a biography.

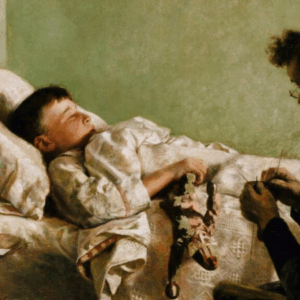

Smith’s novel centers on George Eliot’s strange late-life marriage to John Walter Cross, a family friend twenty years her junior, which is a largely uncharted chapter in her life. Eliot’s chaste and disastrous honeymoon in June, 1880 with her dapper and, as she discovered, bipolar new husband—who tried to commit suicide during their stay in Venice—is the entry point for a sensitive exploration of how Marian Evans, a country girl considered too plain to marry, developed other, more intellectual options fueled by her enchantment with the rich possibilities of language. With her willingness to flout custom, Eliot found the passion and support she needed with George Henry Lewes, her beloved (albeit irrevocably married) companion of 26 years. Devastated by his death, she felt lucky to find another kind of unconventional love with “Johnnie” based on “admiration and kindness” during what turned out to be the last few months of her life.

Asked in an email exchange why novelists are drawn to stories of great writers, Smith replied, “There is a profound and private loneliness to our chosen art, and a longing to find replicas of our own experience in those who’ve gone before us…I was drawn to George Eliot first because she is one of the greatest writers in the English language, and she was a woman…To be a novelist is difficult at best, and to be a woman and a novelist still means to overcome barriers, social, psychological and spiritual. Especially, I think we are still, to some extent, searching for our own identities…Inevitably, we look to other writers as role models.”

“There is a profound and private loneliness to our chosen art, and a longing to find replicas of our own experience in those who’ve gone before us.”

In Smith’s afterword to The Honeymoon—the almost obligatory author’s note separating fact from fiction that accompanies most of these novels—she comments that “writing the book was a little like writing a detective story, a search for clues, a piecing together of facts and inferences.”

J. Aaron Sanders’ Speakers of the Dead, the first of a projected series of “Walt Whitman Mysteries” (published by Plume in March) actually is a literary detective story, part of a growing genre. Sanders, a professor of English literature, spins a fast-paced macabre tale set in 1843 that encompasses political corruption, yellow journalism, and the fight for women doctors and legal autopsies. It is filled with egregious miscarriages of justice, black market grave-robbers who supply medical schools with corpses for anatomical dissections, public hangings, and the vicious slayings of several of young investigative reporter Whitman’s fictional friends, including his boyfriend and editor at the Aurora. Set twelve years before Whitman wrote Leaves of Grass, the novel’s hero is determined to expose rampant corruption and unravel a rash of murders—beginning with the famous unsolved 1841 case of a beautiful cigar girl, Mary Rogers, about whom Edgar Allan Poe wrote the story “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt.”

Sanders comments in his author’s note, “The broad impetus for Speakers of the Dead was to imagine what might have happened to change Walter Whitman the journalist and temperance novelist into Walt Whitman, the American poet.” He adds in an interview, “I look for gaps in history, learn everything I can around them, and then create a story that fills them.”

Speakers of the Dead is one of three novels in this current crop that consider the truth that dared not speak its name, probing the ramifications of repressed homosexuality in a time of zero tolerance—specifically in the lives and works of Melville, Hawthorne and Whitman. (The Honeymoon also touches circumspectly on Eliot’s young husband’s apparent homosexual leanings.)

Mark Beauregard’s The Whale: A Love Story (due from Viking in June) confronts stifled homosexuality most directly. It serves up an intense, sometimes overwrought drama about Melville’s outspoken but thwarted passion for Nathaniel Hawthorne as it plays out during the year they lived near each other in the Berkshires. In Beauregard’s telling, the attraction is mutual, but Hawthorne, doggedly honorable, refuses to betray his wife’s trust. On long walks in the harsh New England weather, Hawthorne and Melville wrangle over theological and moral issues, which color Melville’s anguished revisions of Moby-Dick. The Whale repositions Captain Ahab’s avid pursuit of the great white whale as a tale not just of frustration, “of vengeance, of the longing for something denied” (229) —but a vessel into which Melville poured his unrequited love for Hawthorne.

There’s a special frisson of pleasure in reading about writers’ early struggles when you know what the future holds for them—which in the case of most of these authors is posthumous literary acclaim beyond their wildest dreams. Beauregard captures Melville at a tormented but relatively hopeful juncture, twenty years before Jay Parini’s much bleaker portrait in his 2011 novel, The Passages of H.M.—when Melville’s literary career and financial prospects had been dashed on the rocks of an unappreciative public.

There’s a special frisson of pleasure in reading about writers’ early struggles when you know what the future holds for them—which in the case of most of these authors is posthumous literary acclaim beyond their wildest dreams.

Alison Anderson’s multi-layered The Summer Guest (due from Harper in May) captures a classic Russian theme—the beauty of sadness—with a portrait of friendship between a relatively lighthearted Anton Chekhov and a young woman doctor in Eastern Ukraine blinded by an ultimately fatal brain tumor. They connect for long sun-dappled, riverside conversations during two summers when Chekhov’s family rents a dacha on the Lintvaryovs’ country estate in the late 1880s, when the writer was on the cusp of life-changing fame. Alone among these books, Anderson’s novel straddles past and present as it toggles between pre-Revolutionary and modern-day strife-ridden Ukraine and three distressed women—the dying 19th century diarist Zinaida Mikhailovna Lintvaryov, her Soviet-born British editor and publisher, Katya, who is faced with the collapse of her business and marriage in 2014, and the divorced translator Katya hires, who is trying to forge a new life in rural France. Chekhov serves as a catalyst in their lives, triggering an exploration of how people bend literature to their personal needs.

Like many of these novels, Ashley Warlick’s The Arrangement (published by Viking in February) and Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree (due from Knopf in May) also zero in on their subjects—M.F.K. Fisher and a tellingly unnamed Samuel Beckett, respectively—before their full flowering. A Country Road dramatizes Beckett’s harrowing experiences in Occupied France as a code-cracking courier for the Resistance, during which he narrowly escaped capture by the Gestapo several times as he fled south with the Frenchwoman who became his life partner and eventual wife. Baker builds a convincing case for how Beckett’s experiences in a world shattered by war shaped the dark, spare, tragicomic voice he developed to express the despair, absurdity, and surprising fortitude that characterize human existence.

Unsurprisingly, books about writers often brim with reflections on the power of words and literature, and these novels are no exception. Smith’s George Eliot marvels at “the capacity to give coherence to her existence through language, through the music and the variability and the flexibility of words.” She muses, “Words alone were abstractions, but when they are joined and linked, they could thrill and take possession of the soul. Words were the weapons and playthings of the mind.”

Beauregard’s Hawthorne is especially articulate about his work, explaining to Melville, “I try to exemplify in fiction those spaces in human society where the actual and the imaginary may meet, and each imbue itself with the nature of the other…To me, that is the whole purpose of fiction, to provide us occasions of meditation in which we may find the intersection of the timeless with time.” Speaking more specifically about historical fiction, he says, “You know how it is, Melville, when you create a dramatic story out of historical events that everyone thinks they already understand. People are likely to mistake fancy for fact in your story, and fact for fancy, if facts can be discerned at all any more. The truth, in a fictional work based upon real incidents, speaks as much to the heart as to the head.”

The Summer Guest is on one level a metafictional paean to literature’s capacity to seduce us and make us see the world differently. Like Smith’s Eliot, Anderson’s blind diarist Zinaida writes of her appreciation of words as building blocks, extolling Chekhov’s descriptions, which were “a gift of vision, a way of helping her see the world… What sort of magic was this?”

“Was that not the beauty of fiction, that it aimed closer at the bitter heart of truth than any biography could?”

Anderson, a literary translator as well as novelist, questions whether a book’s provenance should affect its value and touts “the truth of the imagination.” Her translator-character asks, “Just because the voice was not an authentic one from the past, did the words have any less meaning?” And, in a statement that makes the case for all of these meta-literary, quasi-biographical novels, she adds, “Was that not the beauty of fiction, that it aimed closer at the bitter heart of truth than any biography could, that it could search out the spirit of those who may or may not have lived, and tell their story not as it had unfolded, as a series of objective facts recorded by an indifferent world, but as they had lived it and, above all, felt it?…It’s why we read. It’s why we need our writers.”

Obviously, biography and biographical fiction serve different purposes. Sometimes only facts will do—and where would biographical novels be without biographies? But in assessing the attractions of this particular breed of historical novel, I’m reminded of a talk E.L. Doctorow gave about his Civil War novel, The March. When asked why he chose to write the book as fiction, he said, “Well, if you wanted to learn about the Napoleonic Wars, which would you rather read, a Russian history text or War and Peace?”

Heller McAlpin

Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for NPR.org, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, and other publications, and writes the Reading in Common column for The Barnes & Noble Review.