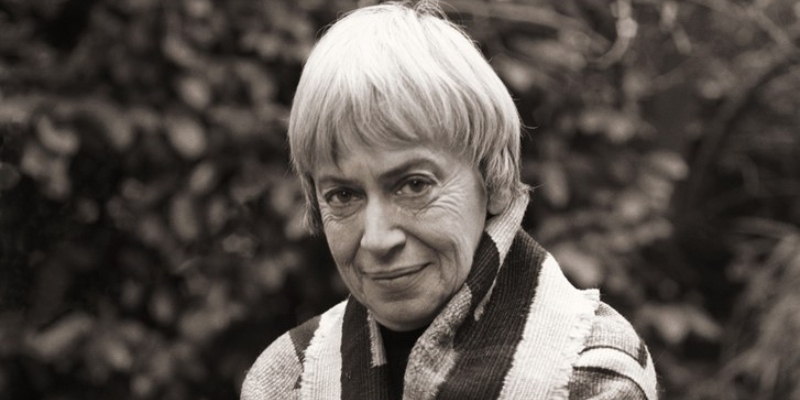

The Journey That Matters is a series of six short videos from Arwen Curry, the director and producer of Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, a Hugo Award-nominated 2018 feature documentary about the iconic author.

In the fourth of the series, Khadija Abdalla Bajaber introduces “There I Am on the Page,” in which Ursula and other writers—including Nisi Shawl and adrienne maree brown—reflect on Ursula’s decision to make many of her characters people of color.

“First Contact with the Gorgonids” was the first Le Guin story I ever read, and the first sci-fi story I read with a truly open mind.

I was in a sort of exile at the time. I’d all but abandoned my family to work on my writing from a small house in deep country. I had a book to get ready and suddenly I didn’t know anything about anything. I keenly felt an unimpressive differentness in my work, felt how different I was in all the ways that mattered but could never be helped. I was meant to create wonder, and all of a sudden—terror. It was lonely. I could not bear trying to explain the feeling to anyone; it felt too pathetic and too unwieldy. I needed to leave, needed to finish the novel: a story about a girl, the sea, and a talking scholar’s cat.

And I was going to read sci-fi.

I didn’t fully understand why science fiction had always pissed me off until adulthood. No matter how well-written, I refused. I was young, and yet even then, something about imagined futures erected a wall over my mind and my heart before I could get into it.

As I got older, I started reading more deliberately. Writers I respected kept recommending sci-fi. Still, I’d resist. I found it either too technical or too self-important. It wasn’t that sci-fi was stupid, but I always felt that it was treating me as though I was, and I could never understand why.

And maybe I misunderstood. Maybe I was too much of a hater to get it the way I was supposed to. In my mind, “classic” sci-fi was about the future. And in these futures, readers could gasp over crimes and injustices that they pretended their world orders weren’t already committing, as if they weren’t the everyday realities of the global south. The genocides we do not call genocides. The fascist undertones of so-called ideal futures, futures where people of color aren’t just invisible but systematically erased. It was real. It was now.

Le Guin talked about the future without using the same center. Or she’d make up something else, something that wasn’t such a drag. She could make utopias interesting. She could critique the delusions of perfect futures, ideas that the publishing industry—and the world at large—didn’t want to notice. Her literary contributions deviated from the Eurocentric narratives of her time: she was one of the few white authors who dared to conceive protagonists that weren’t white men. And because they never appeared on the covers, readers would be deep into the first Wizard of Earthsea book before she surprised them with the info.

In “The Ascent of the North Face,” (another of my favorites), she satirizes the self-important grit and clichés that inundate explorer narratives. In “First Contact with the Gorgonids,” the domineering and entitled husband is familiar to any society beneath the equator burdened with a tourism industry. The story also offers insight into how women observe, adapt, and compartmentalize, so profoundly that its plausibility became its humor. Whom among us hasn’t played stupid so well and so often that it becomes a game—a dangerous one—in and of itself?

To pretend diverse fiction wasn’t being written in Le Guin’s day would be destructive, but it’s true that few publishers gave minorities a chance. Le Guin’s work illuminated the limitations of mainstream Eurocentrism to the people responsible for it. She challenged the writing landscape and the writers who dominated it, forcing them to be aware of what they were actively doing to shut out people unlike them, and what they were passively failing to do to bring them in. She acknowledged the struggles of “otherness,” and she approached otherness without making it villainous.

I read Le Guin’s work at a time when I was struggling to shape worlds that had me and mine in them. To say things that are true, to speak for myself, to do the research. The historical memory of my home is so peopled with authorities not of it. A people will be forgotten only when they are made to forget themselves, which is what happens when we do away with every avenue where they can be heard by their own.

I decided that once I was done studying the classics, I’d get down to business and read sci-fi authored by non-white writers. And I did. Kiko Enjani, Dilman Dila, Shingai Njeri Kagunda are just a few among the many I’ve loved and enjoyed. And in the small house in deep country I read, I wrote, and eventually, I finished my novel.

I have Le Guin to thank for opening my mind to science fiction. It’s not hard to open your mind to her. Often, it’s impossible not to.

—Khadija Abdalla Bajaber, author of The House of Rust

*

Further reading:

Ursula K. Le Guin on Racism, Anarchy, and Hearing Her Characters Speak

“It was incredibly subversive when I started doing it with A Wizard of Earthsea. That’s very curious, that whole thing. There it was absolutely deliberate. I was just tired of all these white heroes.”

What Ursula K. Le Guin Meant to Me: Four Writers Remember

“This, too, is why I loved her: like the ones who choose to walk away from Omelas after seeing the cruel system on which their home is built, she helped make the world—our world, and the ones swirling invisibly-visibly inside us—better.”

Zahia Rahmani on Discovering Ursula K. Le Guin in 2021

“Ursula Le Guin, by the power of the urgency of her thinking, remakes, in front of us, the world. She incessantly remakes maps. But this means that we must undo the constructions that constrain us.”