It had been a touch of incredible fortune to find David one spring night at a dive on Houston Street. He’d been attending a coworker’s farewell gathering, an anomalous outing for him. He was short-haired and clean against the peeling paint and graffiti. That he’d been there that night nursing a Stella Artois, and had needed the restroom at the same time as she, had upended statistical logic. He was taller than everyone, and thinner, as if streamlined for air travel. Not conventionally handsome, but with a narrow, austere face. His green irises seemed lit, like dappled leaves on a forest floor. When he looked at Madeleine, she was briefly paralyzed, a field mouse in a clearing. He bought her a vodka tonic and left a three-dollar tip for the bartender. As he handed the glass to her, turning the tiny straw in her direction, she’d felt the dizzy euphoria of a traveler who has turned onto the right road, the easy expansion of lungs as the horizon opens before her.

He was an account supervisor at a big advertising firm in mid- town, he explained breezily, coordinating campaigns for sneakers and tortilla chips. But later, over a series of ardent dinner dates, she learned that he’d grown up in the country—on a farm, no less—and had never felt truly at peace in an apartment building. Lately he felt that he was being gradually drawn back to Nature, and now that he’d found her, he suggested with elaborate, soft- forested eyes, perhaps his quest was complete. Within six months, they were married and looking at real estate listings.

The house has been sweepingly renovated, the front door framed by columns and topped by a counterfeit balcony. It’s what the real estate agent had termed a center-hall colonial, with the kind of timeless architecture and rigorous symmetry designed to leverage a calming effect on its inhabitants. Paired with precise, harmonious details, she implied, a house like this had the power to transform its owners’ experience of the world, to render any obstacle—any boiler failure or termite siege—surmountable.

Nearly all their money has gone to the down payment, and with the little that remains, Madeleine is scrambling to furnish. With a Sharpie, she circles furniture in soft-lit catalogs: a sectional sofa, a leather armchair, a mirrored console table. Deliverymen put them in place. Still, the rooms echo.

Alone, she wanders the house on the balls of her feet. It is preternaturally quiet, the walls themselves thick with insulation, sealing out the buzz of the world. A sliding glass door displays a wide lawn tumbling to a thumb-smudge of trees. She has reached it at last: this asylum, this glorious valve. Madeleine had first glimpsed this kind of life as a girl, visiting a friend who’d moved to a verdant nook of New Jersey. Entering that house had been like entering a palace: the soaring entrance hall, floors that didn’t sag toward the middle, bay windows looking onto wanton grass and trees, the great yawn of sky. There, she’d learned to ride a bicycle. Pedaling back and forth on that wide blacktop driveway, she’d felt the first ecstasy of flight.

She has never lived anywhere but in a gerbil cage. She has never had money. Her father was a bag-eyed jazz musician— dead in middle age—her mother a schoolteacher who supported them all. Madeleine had diligently sidestepped adulthood in her parents’ lopsided brownstone on Charles Street, among the aging socialists and drag queens. Before meeting David, she had acquired the habits of every cynical city girl: shutting down dirty bars, flattering scrawny musicians, waking Sundays on ripped Naugahyde couches.

Tonight, he is out in the woods, building a tree house for their daughter who is due in a month. Although she will not use it for years, he has thrown himself into the project as if on a deadline. Each evening, when he comes home from work, he puts on old jeans, disappears into the garage, and cuts lumber with a power saw. Madeleine has agreed not to visit the tree house until it is finished. She watches David carry wooden planks over the grass to the woods, the late-summer sun casting his long shadow before him. His hands have become splintered and raw, his forearms welted from the ash tree he has selected.

This is his nature, she knows, this kind of focused work ethic. He lugs home stacks of library books about tree house architecture. At night, he comes into the house with the look of an outdoorsman, in soiled plaid shirts and patch-kneed jeans. Perhaps he has reverted to a forgotten self, his childhood on the farm, when he’d spent whole days in the woods hunting for turtle shells, mouse skulls, snake skins. He works on the tree house later and later each night, until he is coming indoors well after dark. Madeleine does not want to complain. She wants him to feel free in his life with her. For years he has lived as an independent man—but now, with parenthood advancing upon him, perhaps he feels invisible ropes tightening. She wants to show that she understands. He can build a tree house if he wants to.

Alone, she watches the evening news, its galloping sound track bridging one bleak segment to the next. Beyond the glass door, she sees David cross slowly over the grass, his figure becoming part of the deepening evening. At last, his silhouette melts into the dark line of trees. The glass door frames a phantasmagoric reflection of the room’s interior, of Madeleine’s own bulging form. The news anchor begins a dirge about home foreclosures. There is talk of a stimulus package. People will be given old-fashioned things to do with their hands. Madeleine herself is fabulously idle, having finally quit her series of temp jobs. This had been David’s idea. He’d encouraged her to enjoy her pregnancy, to not feel ashamed for staying home with their child if that was what she wanted to do.

She is not accustomed to so much aloneness. Nothing in her old life had ever approached this depth of quiet, this vacuum of night. She imagines animals in the woods surrounding the house, emerging when the sun sets to carry on their dark pursuits. She does not like to think of David out there, but restrains herself from going to retrieve him, from begging him to come inside and sit with her. She does not want to be that kind of woman.

At last, after she has gone to bed, she hears the sliding door. Moments later, he is with her beneath the blanket, whispering apologies. There is a chill in his touch, a suggestion of autumn. He slides up against her spine and a coil loosens inside her. What extraordinary luck, after all: this beautiful place, this wonderful man. At last, a real house with a mailbox and garden hose. A desirable suburb in a sterling school district, not too far from the city. A kind, intelligent husband with a lucrative career and domestic leanings. The child inside her settles itself, and she falls into dreamless sleep.

Over the summer weeks that follow, David returns from work earlier in the afternoon. “Light day,” he tells her, and disappears into the garage. He rushes into the trees with his planks. He comes in only to eat whatever dinner she has made, then goes back out until dark. One night, he does not come in for dinner at all, and Madeleine finds herself crying over turkey tetrazzini. Finally, she puts the food away and climbs into bed in her clothes. After midnight, she hears the sliding glass door. “I’m so sorry,” he tells her in bed. “Sometimes I just lose track of time out there.” Madeleine turns over, too spent to protest, and allows him to put an arm around her. “I know you’re tired of this, but I’m almost done building, I promise. I can’t wait to show it to you.”

She has been sleeping badly, staring through the skylight in the bedroom ceiling, convinced she can see the stars move. David has become progressively more restless at night, twitching his legs like a cricket, muttering garbled syllables. She listens closely, but is unable to decipher any meaning. Tonight, his vague murmurs become louder, insistent. He repeats a strange phrase that sounds like “Up a cat I kill.” His face tightens and he jerks upright, eyes open. A cold current passes through Madeleine’s veins, and she turns on the bedside lamp. David stares at her for a moment without recognition. She rubs his arm tentatively.

“It’s okay, honey. You were just dreaming.”

He gazes for another blank moment, until something in his eyes folds inward and he softens into himself again. He shakes his head. “I’m sorry.”

She keeps rubbing his arm. “What were you dreaming about?”

He is quiet for a moment. “The same dream I’ve been having all week. I’m in the tree house and a strange bird lands on a branch and talks to me.”

“It talks to you? What does it say?”

“Nothing, really. Nonsense.”

“You’ve been having the same dream every night?”

“More or less.”

“Anxiety, I guess,” Madeleine says.

“Probably.”

She turns the light off, and David is silent for the rest of the night. But she stays awake, watching the vibrations of stars through the skylight until they vanish into dawn. It is impractical to have a skylight in the bedroom, of course. Uncovered like this, it allows the morning light into the room—but Madeleine has not yet found an elegant shade for it.

When the alarm rings, David unfolds himself from bed and lurches into the bathroom, pale and dazed as if hungover. Still, he emerges showered and shaven, and in a white button-down shirt and pressed chinos he is an advertising executive again. He kisses Madeleine and goes out to catch the 7:09 to the city.

That afternoon, Madeleine shops for baby clothes and returns to find David lying on the couch with an arm over his face. She feels a primal rush of alarm, as if she has walked in on an intruder. She rests the shopping bag on the mirrored console table.

“What’s wrong?”

“Terrible headache,” he says drily. “It’s been happening a lot lately, but today I just couldn’t get through it.”

Madeleine sits on the edge of a cushion, puts a hand to his forehead.

“You never said anything about headaches. Why didn’t you say something?”

“It was just a headache before. Now it’s worse.”

“You’re warm. Did you take something?”

He blinks at her. “Of course. Nothing helps. It’s like an ache in my whole body. Even my scalp hurts.”

“You need to see a doctor.”

He closes his eyes again. “We don’t have a doctor here.”

“We’ll find one.”

“Just let me rest right now.”

She kisses his forehead and retreats. While she is upstairs arranging the baby clothes in dresser drawers, she hears the sound of the sliding glass door. Outside the nursery window, she sees David go over the grass toward the woods.

***

“I can’t help myself,” he says, when he comes to bed after midnight again. “It’s like the woods are calling me. The only time I feel all right is when I’m up in that ash tree. At work, I can’t sit near the computer. There’s no air in the building.”

“Honey, what’s going on? You never had this problem before,” Madeleine says.

He looks at her for a long moment, then asks quietly, “Do you remember the bird in my dreams?” She nods.

“My mother used to talk about things like that. Dream visitors. I remember she used to have recurring dreams of a mountain lion. It was her guardian animal, she said. She used to ask me if I ever had animal friends in my dreams. I told her I didn’t know what she was talking about.” David smiles weakly. “I used to think she was crazy, or pretending to be eccentric. Once, she made a big papier-mâché sculpture in the yard, a big yellow mountain lion. It was supposed to be a totem to her animal.”

Madeleine does not respond. The sky is clouded tonight, and there is no moon through the skylight, no stars. David’s face is just a shifting patchwork of shadows.

“Anyway, I’ve been thinking about that,” David continues. “I took some books out from the library, just for the heck of it. New Age stuff, about animal dreams and their meanings. There’s a lot out there.”

“I’m sure,” Madeleine says. He props himself up on an elbow. “Can I read you something?”

He turns on the bedside lamp, and Madeleine squeezes her eyes shut. She hears him slide out of bed. When he returns, he is holding a book with a cover illustration of a neon figure shooting laser beams from its fingers and toes. “This one has a whole section about physical symptoms like the ones I’ve been having.” David glances at her with flashing eyes. “Listen to this.”

An individual may be chosen by the spirits to act as a go-between, a kind of messenger between worlds, entrusted with the role of community healer. The chosen individual may be awakened to his calling in a number of ways. He may hear voices or encounter animal spirits in his dreams. He may undergo a profound trial in Nature, characterized by physical symptoms such as headaches, general numbness, and tingling in the scalp. Often, the chosen individual is initially fearful or confused by these signals from the spirit world. He may feel cursed, angry, and resistant to adopting such responsibility. But the alternative is typically worse; rejecting the spirits’ calling may put him at risk of severe depression, even suicide.

Madeleine listens quietly, unable to absorb the words. They arch over her head, as if she is standing behind a waterfall. As she watches David’s face, his latticed irises, a memory comes to her of their first date, when they’d walked downtown along the Hudson. When they’d reached Trinity Church, he had led her through the gate to its weathered graveyard, and they’d wandered among the mildewed headstones. She remembers the way he’d run his hand over the grave markers. As a boy, he told her, he’d spent hours in the old cemetery near his house. He’d made grave rubbings, memorized names, birth dates, death dates. He’d devised detailed life stories for those people: the wives who’d died in childbirth, the grieving husbands who remarried only to be left again. At the time, this had not struck her as peculiar, but as exquisitely sensitive, the mark of a man with untold depths.

He begins to skip shaving in the morning and wears the same pants three days in a row. He leaves the house so late on some mornings that Madeleine knows he will miss his train. There is nothing she can do, she tells herself, except trust. He has come this far in his life without her. He is more of an adult than anyone else she knows. Men, of course, go through transitions and investigations like anyone else. This is normal, healthy. No one is—or should be—completely stagnant and predictable, year after year. This will prove a brief episode, she assures herself. At worst, a midlife crisis.

She goes about her own concerns: choosing paint for the nursery, a runner for the upstairs hall. She prepares a macaroni- and-cheese casserole for her first book club meeting. The invitation had come from a neighbor named Rosalie Warren, who’d swooped in the wake of their moving van with a tray of lemon bars. Her army of children is impossible to ignore, patrolling Whistle Hill Road on bikes and scooters, peering into the windows of parked cars.

Madeleine pulls on a white eyelet maternity dress and carries the casserole the half mile to Rosalie’s house. Arms aching, she shuffles up to the brick facade with an oval window like a third eye above the door. Flowering shrubs flank the walkway, and on the front step a shoe brush grows from a stone hedgehog’s back. Feeling watched, she rubs the soles of her sandals over it.

Inside, women mingle in shades of melon and chartreuse. The furniture is permanent-looking: a vast coffee table of distressed wood, armchairs of cream-colored linen. Madeleine’s tub of macaroni sits on the buffet like a fat girl among asparagus wraps. The women gather on tufted dining chairs and discuss the book selection, In the Path of Poseidon, a memoir of a man who sailed around the world with his family. They dive right in. The author was reckless, they agree, to endanger his wife and children in this way. They could have been killed.

Madeleine listens, nodding when appropriate. She thinks of David, surely home already, huddled in the woods. A flare of something like dread goes through her body. She is uncomfortable in her chair, unable to cross her legs, forced to squeeze them together. She curses herself for wearing such a short dress. The women volley their opinions around her. Within half an hour, the conversation has devolved into a lament about the economy, worry that husbands will be laid off, that home renovations will have to wait. The book is not mentioned again.

After the meeting, Madeleine walks home. Some of the women drive past, their headlights illuminating the macaroni tub in her arms, still nearly full. Her next-door neighbor Suzanne—whom she has just met—rolls slowly alongside in a Range Rover like an abductor, but Madeleine politely tells her she prefers to walk. It is good to do this, she thinks, to breathe the night air, absorb her new habitat. As Suzanne’s engine dies out, the only sound remaining is that of her own sandal steps. The darkening sky is the color of the open sea, bare and boatless. All around, windows smolder with lamplight. The seafaring author is indoors somewhere with his family now, sheltered in some American home, perhaps looking out a window at this same nautical sky, pining for the sway and jostle of water beneath him.

She finds David on the couch, barefoot, eating ice cream. He smiles as she comes in the door, as if he has been waiting for her. “It’s the end of an era,” he says, holding up his bowl. “I’m done with work.”

Madeleine puts the casserole on the console table. “What do you mean?”

David sucks on his spoon. “I mean I’m not going back.”

She steps into the living room. “You didn’t quit.”

“No, not exactly.” He crosses his legs, exposing overgrown toenails, curled and yellow as claws. “They asked me to leave.”

“You were fired?”

“I would have left anyway.”

Madeleine feels an immediate numbness in her face, as if the blood is blockaded in her veins. She drops onto the large leather easy chair, newly purchased for a thousand dollars.

“I can’t use the computer anymore,” David says simply. “The sound is awful, and it gives off a toxic emanation. I know I’ve been sensitive lately, but I can’t even sit at my desk when it’s on.”

Madeleine stares at him, at the ice cream bowl in his hand, the simian feet. “David, this was never a problem before.”

He shrugs.

Madeleine leans forward, grips the arms of the chair. Controlling her breath, she says, “What are you telling me? You’re telling me they fired you.”

David looks away, giving her his profile. He seems to be playing some memory in his mind. There is an unnerving little smile on his lips. A long moment extends, a bloated silence, and Madeleine realizes she has been holding her breath. She lets out a slow wheeze.

“How are we going to pay the mortgage?” she says softly.

“I have a plan.” He glances at her with a weird light in his eyes. “You have to trust me.”

In the pause that follows, Madeleine remembers her first visit to his childhood home in Pennsylvania, with wind chimes on the porch and laundry in the front yard. Inside, David’s gray- braided parents sat at a big wooden table, churning apple butter. Incense burned on the counter beside a statuette of Krishna. In his oxford shirt and loafers, David appeared as foreign to this environment as his parents were native. How strange, she’d thought, that something so strong and unbendable had been forged by this queer fire.

In the pause that follows, Madeleine remembers her first visit to his childhood home in Pennsylvania, with wind chimes on the porch and laundry in the front yard. Inside, David’s gray- braided parents sat at a big wooden table, churning apple butter. Incense burned on the counter beside a statuette of Krishna. In his oxford shirt and loafers, David appeared as foreign to this environment as his parents were native. How strange, she’d thought, that something so strong and unbendable had been forged by this queer fire.

“Trust me,” David repeats.

Madeleine studies his face. He appears to be the same man. A man who has never given her a reason not to trust him. She had so easily, eagerly, fallen into the habit of trust. In their wedding vows, when they had promised to help each other achieve their dreams, to stand beside each other through any difficulty, it had seemed that the words were skewed to her benefit. It had never occurred to her, really, that she would be called upon.

“I think I can find a way to harness this,” David says.

“Harness what?” Madeleine asks. “I don’t understand.”

“I’m thinking I can learn traditional healing techniques and open an independent practice.”

Madeleine stares. “You’ve been in advertising for fifteen years.”

“It’s a career change, yes. People change careers all the time.”

“But the timing, David. We’re about to have a baby.”

He smiles. “Babies are born all over the world, to all kinds of people.”

“What does that mean?”

David is quiet. After a moment, he says, “What if I wanted to go to law school? Would you support that?”

There is a touch of impatience in his voice that Madeleine has never heard before. She sits for another moment, then rises to her feet, steadying herself on the back of the chair. “Listen,” she says. “You can keep talking, but I’m going to go make dinner.”

He follows her into the kitchen. “I know you’re upset.” She pours rice into a measuring cup without measuring it and fills a pot with water. She seizes a blind assortment of vegetables from the refrigerator and begins chopping. He stands beside her. “Listen to me. I think the bird is a messenger inviting me to change course. I’m luckier than some people, who never receive a tangible sign. They just feel sick and never know why.”

Madeleine gazes at the cutting board, where she has created a heap of cubed carrot, potato, cucumber. She slides the vegetables into a pot and her eyes alight on the backsplash behind the stove, a grid of glossy bloodred tiles. This is one of the details she’d loved about the house, but which now strikes her as superfluous.

David puts a hand on her arm. “I believe I’ve received a gift, Madeleine. I believe I’ve been selected for something very strange and wonderful.”

She turns to him and sees the fevered eyes of a teenager who has just discovered beat poetry. Her own face heats. She should have known that this was inside him all along, like a time bomb. This is what he came from, what he is made of. His corporate adventure—his visit to the culture of work, of responsibility—was just that, an adventure. A rebellion against his upbringing, short-lived. What she is witnessing now, she suddenly understands, is a return to his roots, his true character. The truth detonates before her.

And is it surprising that she would align herself with someone like this, after all? People are drawn to those like themselves. On a deep level, they recognize themselves in others, so that every couple is, at the core, properly matched. Like his corporate charade, her own transformation into suburban housewife has been a hoax. She is an imposter in this place, in this house. She stands at the kitchen sink, before the wide window that is still missing treatments, and feels that the whole town can see in.

“I think a healing practice would fill a real need,” David is saying. “People are looking for release from the ills of modern culture. So many of us are disconnected from Nature, from our spiritual selves, and it’s making us sick. It’s endemic to the whole country, don’t you think? It’s something I’ve always suspected in some low-grade way, but kept pushing aside. Don’t you feel like that, deep down? Don’t you just rationalize it away?”

Madeleine takes the pot from the burner and slops the vegetables onto a platter.

“Maybe they’ll take you back,” she says.

David stares. “Haven’t you been listening? I don’t want to go back.”

Madeleine brings the platter down on the counter. “I can’t believe I’m hearing this. We just bought this house, David. We’re having a baby.”

As she speaks, her body sways as if upon a boat. Another memory returns from her visit to David’s childhood home, one curious moment. Washing her hands in the rustic powder room, Madeleine had looked out the window to see David in the yard, standing beside a pole birdfeeder, its clear plastic silo filled with seed. As he stood, tall and still, Madeleine watched a sparrow circle the feeder and alight. Then a crow. As she stood at the powder room window, the feeder had swelled with birds.

David spends his first day of unemployment thumbing library books on the couch. Madeleine slips out of the air-conditioned house and into a kiln. She lumbers down Whistle Hill Road, past flat-faced houses blinking back the noonday sun, past the little pond furred with algae. She keeps a small, purposeful smile on her face, but is unable to rid herself of the sense that she is being watched, as if her husband’s aberration is visible upon her like a jumpsuit. There are men in the periphery of her vision, trimming bushes, washing cars. There are the low growls of lawnmowers and chain saws. David hasn’t mowed their lawn in over a month.

That night, David stays in the woods, in the ripped blue sleeping bag of his boyhood. Madeleine lies alone in bed with a hand on the globe of her belly, deciphering the changes in its temper. There is a sense of agitation, of looming implosion. There is a swoon of adrenaline as her abdomen stiffens, becomes hard as a watermelon. She gasps and fixes her eyes on the skylight, a black velvet kerchief crusted with stars.

The adrenaline waves proliferate, building on themselves, in the pattern of the panic attacks she’d had as a younger woman. She has learned to breathe through these, to carve a space for herself, as she would do when negotiating a crowd in Midtown.

At last, when the breathing becomes impossible, she crawls from bed and goes outside with a flashlight. She edges over the dark carpet of grass, stopping to clutch herself. In the woods, she follows a narrow path, twigs snapping, and sweeps her flashlight over the barbed branches. At last she illuminates a crude box suspended in a forked tree trunk. She calls to David.

They name the baby Annabel. The first weeks are suspended out of time, a dream of sleeping and nursing. David is mercifully silent on the topic of his spiritual vocation. It isn’t until Annabel is two months old that he comes to Madeleine with a library book, an almanac of South American fauna. Without speaking, he opens the book to a full-page photograph of an ebony bird poised upon a branch, a crest like a standing wave upon its head. Its eye is small and hard, a jet bead ringed with white, and there is a long protuberance like an empty black kneesock beneath its beak. The bird gives an impression of cool majesty, of indifference to human quandary.

“It’s an Amazonian umbrella bird,” David whispers after a moment. “All I know is that it has a loud call, but is rarely seen. It lives its whole life in the rain forest canopy in Brazil and Peru. The male courts the female by stretching out his wattle, but then the female builds the nest and raises the chicks alone.”

“Leave it to Nature,” Madeleine says. “I’d love to see it in person one day.” He spends the rest of the week designing a logo—a black silhouette of a crested bird in flight—for an ad that will run in the local newspaper and the kinds of free magazines provided at spas and yoga studios. By the end of the month, he has his first appointment.

When the client arrives at the house, Madeleine hides in the bedroom with the baby. She watches from the upstairs window as a young man approaches the door, a silver bull ring glinting at his nose. The Warren children are probably running indoors right now, she imagines, calling to their mother. Perhaps Rosalie, at this moment, is dialing for a patrol car.

For the hour that David spends in the tree house with the stranger, Madeleine sits nursing Annabel, examining the same few pages of a novel. When the men finally come back through the house, they are laughing. She remains upstairs until David knocks.

“It went amazingly well,” he announces. “Rufus was perfect to work with, so cooperative. He’s trying to overcome a drug addiction.” He holds up a bouquet of twenty-dollar bills. “Not bad for an hour.”

“It went amazingly well,” he announces. “Rufus was perfect to work with, so cooperative. He’s trying to overcome a drug addiction.” He holds up a bouquet of twenty-dollar bills. “Not bad for an hour.”

Madeleine closes her book and funnels her whole heart into a smile.

More clients come in the next few months, smiling bashfully at Madeleine and Annabel as they pass through the house to the backyard. They go over the grass and into the woods: large women in caftans, thin girls in yoga pants, ponytailed men. At first there are two or three a week. Then one a day. By the winter, David is juggling several appointments on each square of the kitchen calendar.

“Where do they come from?” Madeleine asks.

“All over. My client this morning came down from Hartford.”

“How do they know about you?”

“There’s a very tight community. Word spreads fast.” Today he is wearing something new: a leather cord necklace with a small pouch attached. “It’s a medicine bundle,” he says, following her gaze. “It’s where I keep tokens that bring me closer to my spirit animal.” Madeleine asks what kind of animal this might be. “I’m not supposed to tell you, but I bet you can guess.” From a pocket, he removes a second leather pouch and shows it to her. “A bundle for the baby.”

Madeleine gazes at the pouch. It is made of soft leather that begs to be touched. She reaches for it, takes it from David’s hand. The leather is puckered neatly at the top, and there is a clink of hidden objects within. An amulet.

“I’d like to journey on her behalf,” David says. “And meet with her animal. Would you help me?”

“Journey where?”

“To the Lower World,” he answers matter-of-factly. Madeleine is quiet. Her husband is in front of her, behind the rough reddish growth of beard, speaking of spirit worlds. She looks at the leather pouch again. She looks at the baby in her arms, built from nothing.

That night, she sits on the nursery floor with a drum in her lap. On the baby’s changing table is a plastic bag labeled Spirit Warrior Music & Instruments.

“It’s not perfect, but it’s something to practice on for now. Eventually I’ll make my own drum out of maple and rawhide.” David stretches out on the sand-colored carpet. Annabel lies on her back in the bassinet, cycling her legs. The winter sun has gone down, and the room is quiet and dark. The windows make a grid of indigo sky. It is not difficult to imagine that the three of them are alone in the universe. “The drumbeat is a bridge to the World Tree,” David tells her from the floor, “giving me access to the branches that lead to the Upper World, or to the roots that tunnel to the Lower World.”

“Is that in one of your books?”

“More than one.” David closes his eyes. “Check your watch before you start drumming. Just start out with a nice, slow beat. When you’ve been going for about ten minutes, go ahead and change to a callback rhythm. Something faster, like a gallop.”

“To call you back?”

“I’ll hopefully be down pretty deep, but I’ll perceive the change in the drum’s tempo and know it’s time to return.”

Madeleine tests the drum. The hard surface is made of a polished synthetic that stings her palms. The sound it makes is flat and unsubtle, like something heavy dropping to the floor again and again. The effect is the opposite of soothing.

“There, keep it going like that.”

Madeleine’s legs are already starting to cramp in their pretzeled arrangement. Although there is no direct sight line from neighboring houses, she wishes with a sudden fervor that she had closed the curtains. She wishes that she had not agreed to do this, that she could switch bodies with any of her neighbors. She thinks of Suzanne Crawford in the irreproachable house next door and desperately wants to be doing whatever she is doing—sipping Pinot Grigio at a kitchen island, loading the dishwasher, paying bills.

The drumbeat is tediously slow, the plodding of an old draft horse. Within a few moments Madeleine’s hands have begun to fall mechanically, driven by their own momentum, and the strident thumps have dulled into sameness. David appears to go to sleep. She continues to hit the drum, resigned, a trudging giant in the nursery.

Watching, she notices gradual changes in David’s face. His eyeballs flicker under the lids like goldfish in a bag. His mouth moves slightly, as if he is speaking to an unseen companion. The baby’s legs finally stop cycling. Squares of blue light fall upon the carpet, and the room is suffused with something sublime and church-like. Madeleine closes her eyes. She pictures David’s tree house, dimly, in the branches of the ash. She entertains the idea of embracing the trunk of the tree and being pulled downward into the ground. Is this how it goes? As she drums, she extends the script, sinking down through the earth, following the tree roots through the soil, to—what?—a sloping underground tunnel. Here, her imagination stalls. What should lie at the bottom? A dark pool of water, or a grassy clearing, or a cave of molten rock. She settles on the pool of water, hovers above it, conjures murky creatures beneath the surface.

When she opens her eyes again, Annabel appears to be asleep. It has easily been ten minutes since she began drumming. At last, her hands pause, then drum again faster. As she does this, she imagines David racing up through a tunnel as through a mine shaft. She looks for evidence of this effort in his face, but it remains placid, as serene as the face of their sleeping daughter. She beats the drum and closes her eyes. She is in a coal car barreling underground, dimly aware of the turns and dips ahead. There may be water, there may be rock. It is not for her to know the way.

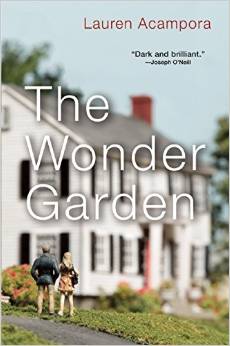

From THE WONDER GARDEN. Used with permission of Grove Press. Copyright © 2015 by Lauren Acampora. Images courtesy of Thomas Doyle.