The Secret Literary History of Some of Your Favorite Colors

Yellow Books, L. Frank Baum's Emerald, and The Color Purple

Yellow

Oscar Wilde was arrested outside the Cadogan Hotel in London in April 1895. The following day the Westminster Gazette ran the headline “Arrest of Oscar Wilde, Yellow Book Under His Arm.” Wilde would be found officially guilty of gross indecency in court a little over a month later, by which time the court of public opinion had long since hanged him. What decent man would be seen openly walking the streets with a yellow book?

The sinful implications of such books had come from France, where, from the mid-19th century, sensationalist literature had been not-so-chastely pressed between vivid yellow covers. Publishers adopted this as a useful marketing tool, and soon yellow-backed books could be bought cheaply at every railway station. As early as 1846 the American author Edgar Allan Poe was scornfully writing of the “eternal insignificance of yellowbacked pamphleteering.” For others, the sunny covers were symbols of modernity and the aesthetic and decadent movements. Yellow books show up in two of Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings from the 1880s, Still Life with Bible and, heaped in invitingly disheveled piles, Parisian Novels. For Van Gogh and many other artists and thinkers of the time, the color itself came to stand as the symbol of the age and their rejection of repressed Victorian values. “The Boom in Yellow,” an essay published in the late 1890s by Richard Le Gallienne, expends 2,000 words proselytizing on its behalf. “Till one comes to think of it,” he writes, “one hardly realizes how many important and pleasant things in life are yellow.” He was persuasive: the final decade of the 19th century later became known as the “Yellow Nineties.”

Traditionalists were less impressed. These yellow books gave off a strong whiff of transgression, and the avant-garde did little to calm their fears (for them the transgression was to return. Just as the narrator reaches his defining ethical crossroads, a friend gives him a yellow-bound book, which opens his eyes to ‘the sins of the world’, corrupting and ultimately destroying him. Capitalizing on the association, the scandalous, avant-garde periodical half the point). In Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, published in 1890, it is down the moral rabbit hole of such a novel that the eponymous antihero disappears, never

The Yellow Book was launched in April 1894. Holbrook Jackson, a contemporary journalist, wrote that it “was newness in excelsis: novelty naked and unashamed . . . yellow became the color of the hour.” After Wilde’s arrest a mob stormed the publishers’ offices on Vigo Street, believing they were responsible for the “yellow book” mentioned by the Gazette. In fact, Wilde had been carrying a copy of Aphrodite by Pierre Louÿs and had never even contributed to the publication. The magazine’s art director and illustrator, Aubrey Beardsley, had barred Wilde after an argument—he responded by calling the periodical “dull,” and “not yellow at all.”

Wilde’s conviction (and the failure soon after of The Yellow Book) was not the first time the color had been associated with contamination, and was far from the last. Artists, for example, had numerous difficulties with it.

Two pigments they relied on, orpiment and gamboge, were highly poisonous. It was assumed Naples yellow came from Mount Vesuvius’s sulfurous orifice well into the mid-20th century, and often turned black when used as a paint; gallstone yellow was made from ox gallstones, crushed and ground in gum water; and Indian yellow was probably made from urine.

In individuals, the color betokens illness: think of sallow skin, jaundice, or a bilious attack. When applied to mass phenomena or groups the connotations are worse still. Hitched to “journalism” it indicates rash sensationalism.

The flow of immigrants into Europe and North America from the East and particularly China in the early 20th century was dubbed the “yellow peril.” Contemporary accounts and images showed an unsuspecting West engulfed by a subhuman horde—Jack London called them the “chattering yellow populace.” And while the star the Nazis forced Jews to wear is the most notorious example of yellow as a symbol of stigma, other marginalized groups had been forced to wear yellow clothes or signs from the early Middle Ages.

Perversely, though, yellow has simultaneously been a color of value and beauty. In the West, for example, blonde hair has long been held up as the ideal. Economists have shown that pale-haired prostitutes can demand a premium, and there are far more blondes in advertisements than is representative of their distribution among the population at large. Although in China “yellow” printed materials like books and images are often pornographic, a particular egg-yolk shade was the favored color of their emperors. A text from the beginning of the Tang dynasty (ad 618–907) expressly forbids “common people and officials” from wearing “clothes or accessories in reddish yellow,” and royal palaces were marked out by their yellow roofs. In India the color’s power is more spiritual than temporal. It is symbolic of peace and knowledge, and is particularly associated with Krishna, who is generally depicted wearing a vivid yellow robe over his smoke-blue skin. The art historian and author N. Goswamy has described it as “the rich luminous color [that] holds things together, lifts the spirit and raises visions.”

It is perhaps in its metallic incarnation, however, that yellow has been most coveted. Alchemists slaved for centuries to transmute other metals into gold, and recipes for counterfeiting the stuff are legion. Places of worship have made use of both its seemingly eternal high sheen and its material worth to inspire awe among their congregations. Medieval and early modern craftsmen, known as goldbeaters, were required to hammer golden coins into sheets as fine as cobwebs, which could be used to gild the backgrounds of paintings, a highly specialized and costly business.

Although coinage has lost its link with the gold standard, awards and medals are still usually gold (or gold-plated), and the color’s symbolic value has left its mark on language too: we talk of golden ages, golden boys and girls, and, in business, golden handshakes or goodbyes. In India, where gold is often part of dowries and has traditionally been used by the poor instead of a savings account, government attempts to stop people hoarding it have resulted in a healthy black market and an inventive line in smuggling. In November 2013, 24 gleaming bars, worth over $1 million, were found stuffed into an airplane toilet. Le Gallienne noted in his essay that “yellow leads a roving, versatile life”—it is hard to disagree, even if this is probably not what the writer had in mind.

*

Purple

In The Color Purple, the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel by Alice Walker, the character Shug Avery seems at first like a superficial siren. She is, we are told, “so stylish it like the trees all round the house draw themself up tall for a better look.” Later, though, she reveals unexpected insightfulness, and it is Shug that supplies the novel’s title. “I think it pisses God off,” Shug says, “if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it.” For Shug purple is evidence of God’s glory and generosity.

The belief that purple is special, and signifies power, is surprisingly widespread. Now it is seen as a secondary color, sandwiched in artists’ color wheels between the primaries red and blue. Linguistically, too, it has often been subordinate to larger color categories—red, blue, or even black. Nor is purple, per se, part of the visible color spectrum (although violet, the very shortest spectral wavelength humans can see, is).

The story of purple is bookended by two great dyes.

The first of these, Tyrian, a symbol of the wealthy and the elite, helped to establish the link with the divine. The second, mauve, a man-made chemical wonder, ushered in the democratization of color in the nineteenth century. The precise shade of the ancient world’s wonder dye remains something of a mystery. In fact purple itself was a somewhat fluid term. The ancient Greek and Latin words for the color, porphyra and purpura respectively, were also used to refer to deep crimson shades, like the color of blood.

Ulpian, a third-century Roman jurist, defined purpura as anything red other than things dyed with coccus or carmine dyes. Pliny the Elder (ad 23–79) wrote that the best Tyrian cloth was tinged with black.

Even if no one is quite sure precisely what Tyrian purple looked like, though, the sources all agree it was the color of power. While he griped about its odor, which hovered somewhere between rotting shellfish and garlic, Pliny had no doubt about its authority:

This is the purple for which the Roman fasces and axes clear a way.

It is the badge of noble youth; it distinguishes the senator from the knight; it is called in to appease the gods. It brightens every garment, and shares with gold the glory of the triumph. For these reasons we must pardon the mad desire for purple.

Because of this mad desire, and the expense of creating Tyrian, purple became the symbolic color of opulence, excess, and rulers. To be born into the purple was to be born into royalty, after the Byzantine custom of bedecking the royal birthing chambers with porphyry and Tyrian cloth so that it would be the first thing the new princelings saw. The Roman poet Horace, in his The Art of Poetry written in 18 bc, minted the phrase “purple prose”: “Your opening shows great promise, / And yet flashy purple patches; as when / Describing a sacred grove, or the altar of Diana.”

Purple’s special status wasn’t confined to the West.

In Japan a deep purple, murasaki, was kin-jiki, or a forbidden color, off-limits to ordinary people. In the 1980s the Mexican government allowed a Japanese company, Purpura Imperial, to collect the local caracol sea snail for kimono dyeing. (Unsurprisingly, a similar Japanese species, Rapana bezoar, is vanishingly rare.) While the local Mixtec people, who had been using the caracol for centuries, milked the snails of their purple, leaving them alive, Purpura Imperial’s method was rather more fatal for the snails, and the population went into freefall. After years of lobbying the contract was revoked.

Like many special things, purple has always been a greedy consumer of resources. Not only have billions of shellfish paid dearly to clothe the wealthy; sources of slow-growing lichens like Roccella tinctoria, used to make archil, have been overexploited, forcing people to look further afield or do without. Even mauve required vast quantities of raw produce: in the early stages it was so demanding of scarce raw material that its creator, William Perkin, later admitted that the whole enterprise was close to being abandoned.

Luckily for Perkin, his new dye became immensely fashionable, and the prospect of the fortunes to be made meant that an explosion of other aniline colors followed swiftly on mauve’s heels. Whether this was also good for purple is another matter. Suddenly everyone had access to purple at a reasonable price, but they also had access to thousands of other colors too. Familiarity bred contempt, and purple became a color much like any other.

*

Emerald

It was Shakespeare who cemented the relationship between green and envy. With The Merchant of Venice, written in the late 1590s, he gave us “green-eyed jealousy”; in Othello (1603), he has Iago mention “the green-ey’d monster, which doth mock / The meat it feeds on’.

Prior to this, during the Middle Ages, when each deadly sin had a corresponding color, green had been twinned with avarice and yellow with envy. Both human failings were the guiding principles in a recent saga concerning a vast green stone, the Bahia emerald.

Emeralds are a rare and fragile member of the beryl family, stained green with small deposits of the elements chromium or vanadium. The best-known sources are in Pakistan, India, Zambia, and parts of South America. Ancient Egyptians mined the gemstones from 1500 bc, setting them in amulets and talismans, and they have been coveted ever since.

The Romans, believing green to be restful to the eyes because of its prominence in nature, pulverized emeralds to make expensive eye balms. The emperor Nero was particularly enamored with the gem. Not only did he have an extensive collection, he was also said to use a particularly large example as proto-sunglasses, watching gladiator fights through it so that he wouldn’t be bothered by the glare of the sun. When L. Frank Baum wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, he used the precious stone as both the name and the building material for the city his heroine and her band of misfit friends are trying to reach. The Emerald City, at least at the beginning of the book, is a metaphor for the magical fulfillment of dreams: it lures the characters in because they all want something from it.

The Bahia was heaved from the beryllium-rich earth of northeastern Brazil by a prospector in 2001. Stones from this area are generally not worth much; they tend to be cloudy and occluded and sell for, on average, less than $10. This one, however, was gargantuan. The whole lump weighed 840 pounds (roughly the same as a male polar bear) and was thought to contain a Kryptonite-green gem of 180,000 carats. In the years since its discovery the gemstone’s vast size and value have done little to secure it a stable home. Housed in a warehouse in New Orleans in 2005, the Bahia narrowly escaped the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina. It has allegedly been used in any number of fraudulent business dealings—a judge called one such scheme “despicable and reprehensible.” It was listed on eBay in 2007 for a starting price of $18.9 million and a “buy-it-now” price of $75 million. Gullible potential buyers were regaled with a backstory that involved a journey through the jungle on a stretcher woven from vines and a double panther mauling.

At the time of writing the Bahia emerald is valued at around $400 million and is at the center of a California lawsuit. Around a dozen people claim to have bought the stone fair and square in the 15 years since it was discovered, including a dapper Mormon businessman; a man who says he purchased it for $60,000, only to be tricked into believing it was stolen; and several of the people who brought it over to California in the first place. An international row has been brewing too: Brazil claims that the stone should be repatriated. The story of the Bahia emerald is, in short, a parable of avarice worthy of the Bard himself.

__________________________________

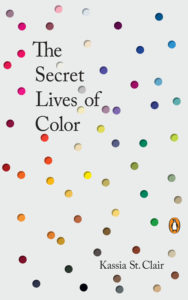

From The Secret Lives of Color. Used with permission of Penguin Books. Copyright 2017 by Kassia St. Clair.

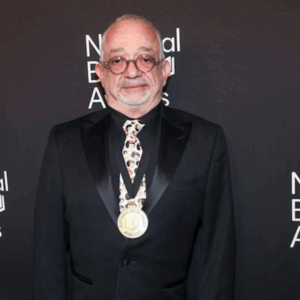

Kassia St. Clair

Kassia St. Clair is a freelance journalist and author based in London. She graduated from Bristol University with a first-class honors degree in history in 2007 and went on to do a master’s degree at Oxford. There she wrote her dissertation on women’s masquerade costumes during the eighteenth century and graduated with distinction. She has since written about design and culture for publications including The Economist, House & Garden, Quartz, and the New Statesman. She has had a column about color in Elle Decoration since 2013 and is a former assistant books and arts editor for The Economist.