The Magic and Risk of a Handwritten Letter

When Sent, Our Careful Construction is Turned into Vulnerability

‘Guten Tag,’ I say to Herr Schroeder when I meet him. ‘Tag,’ he nods his head and smiles vaguely. Herr Schroeder is our postman. Although I don’t often speak to him, he is the only person I see every day.

Herr Schroeder collects stamps. ‘Keep me any interesting ones, especially those new, Croatian, ones,’ he says. ‘Just leave them for me on top of your postbox.’

And I do, almost lovingly.

Dubravka Ugrešić, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender

*

It is perhaps the obvious thing, to point to the materiality of the letter: how it’s written on paper, maybe folded and slid into a stamped envelope and sent par avion. But that materiality, in an era of email and text messages, has become the essential quality of the medium. In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin considers how the modern capacity for reproduction affected original artworks, or rather, our (mediated) perception of those originals: “Even in the most perfect reproduction, one thing is lacking: the here and now of the work of art—its unique existence in a particular place. It is this unique existence—and nothing else—that bears the mark of the history to which the work has been subject.” It is hard to say what constitutes the “original” in email correspondence, which exists in multiple forms: in drafts, inboxes, and sent folders, cc’d and bcc’d, so on and so forth. But the handwritten letter does have all the ingredients that make an original: a singular “here and now,” a “unique existence in a particular place.” Letters on paper bear the mark of history. They show the trace of touch in fingerprints and coffee stains. And countless readings render scars in brittle paper, unfolded and folded up again.

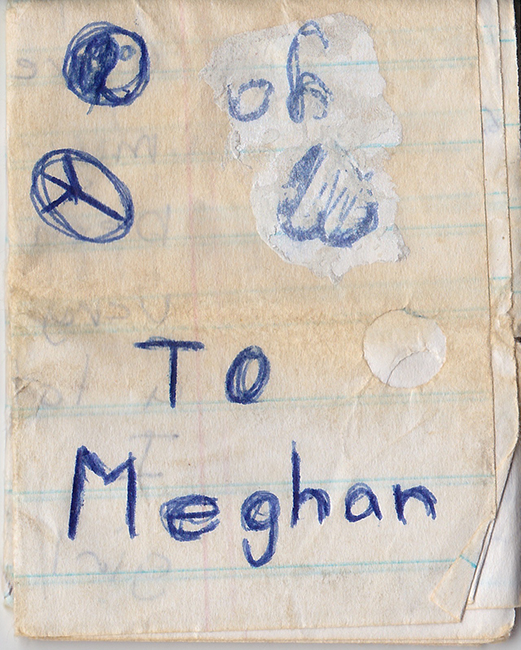

I have a letter like that, from my 7th grade boyfriend. He wrote it out on a piece of lined and 3-hole punched notebook paper and folded it into a tiny square no larger than a quarter, so small that another fold would not have been possible. But despite these diminutive dimensions and the decades that divide the moment he wrote this epistle from our present, I still have this letter. I’ve moved often in the years since receipt—from Los Angeles to New York to Prague to Ann Arbor to Berlin to Austin and back to New York—and that little letter is not lost. Its folded corners are now nothing at all, just holes where the corners used to be. A few summers ago, newly thirty and moving again, I came across the letter and for the first time wondered about a white-out mark on the outside surface, hiding something from that younger me.

In that moment of consuming curiosity, I took a kitchen knife and scraped at that blotch of white-out, until I could make out what was written underneath: “I [heart] U.” At 30, I had the same reaction I imagine I would have had in the 7th grade were I so forensically inclined then. Really?! I think. He loves me?! Well, loved me. And maybe not really loved me. After all, he has drawn the symbol in lieu of the word, the (pre-Emoji era) universal middle school jargon for going steady, nothing more, nothing less. But still . . . it is somehow a flattering discovery. A moment of blushing transpires. I wonder whatever happened to Jesse Taylor. Rereading his letter, I am reminded that he was kind and funny, and the first in a string of boyfriends who could not spell to save his life. I patch together a few blurry memories of this person with whom I shared a brief past; I am lost in a cloud of nostalgia in my kitchen, knife in one hand, letter in the other.

At the end of Swann’s Way, the first book in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the narrator looks back with longing on the Parisian boulevards of his childhood at the turn of the twentieth century, which have since given way (“alas!”) to “nothing but motor-cars driven each by a moustached mechanic.” He wonders if the places he carries in his mind “were indeed as charming as they appeared to the eyes of memory.” And perhaps I ought to ask the same question: is this fondness I have for the 7th grade love letter, or any other number of epistolary treasures I have accumulated over the years, simply what Proust concludes to be “a fetishistic attachment to the old things?”

But if I am constructing in memory something altogether different—more romantic, elegant, exciting—than what was the reality (and I most certainly am), then that is the very kindness of the surviving letter. It will not speak up with interjections or revisions.

Reading old letters is a process of composing a narrative out of what is left. The gaps inherent in this method, generated by lost letters and unrecorded conversations, are what make the epistolary so alluring to me. The narrative gaps created out of what is lost or falsely remembered provide space for imagination, for conjuring what was said in those blank spaces. To construct a narrative around letters that remain is to write a story that yawns wide with holes. (“How paradoxical it is to seek in reality for the pictures that are stored in one’s memory,” writes Proust, “which must inevitably lose the charm that comes to them from memory itself.”)

But this thing that I find so enticing in reading letters, is precisely what makes writing them so risky. If letter writing is ultimately a work of fiction in which we construct ourselves in the way we would like to be perceived by our recipients, that control is relinquished the moment we let go of what we have written. Our careful construction is turned into vulnerability, at the mercy of the recipient’s interpretation (or worse, inattention).

Emily Dickinson thought about the risk inherent in written correspondence. In one of her “fragment” poems—written on envelopes and other paper scraps—she wrote, “What a Hazard a Letter is— / When I think of the Hearts it has Cleft or healed I almost wince to lift my Hand to so much as a superscription.” Critic Mark Ford, in the London Review of Books, has described Dickinson’s unsent envelope poems as “telling emblems of her urge to communicate, and her almost equally strong urge to withhold communication.”

I submit that these opposing desires are not singular to Dickinson, that this inner conflict is the reason behind many written letters that have gone unsent.

*

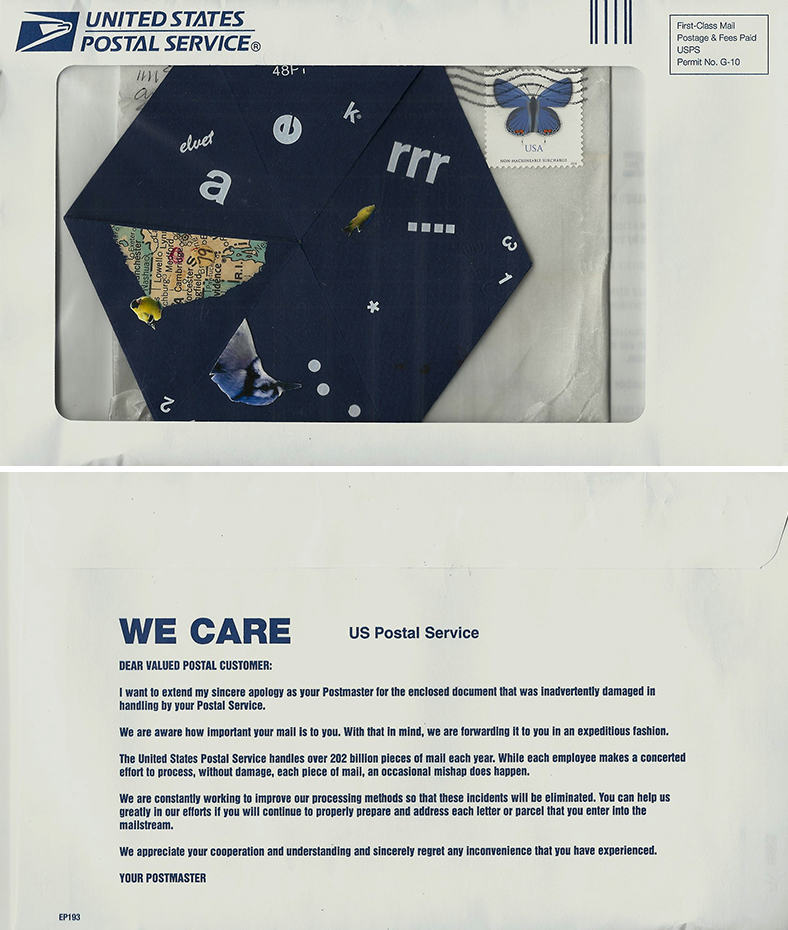

But if one does muster the courage to mail the letter, there is the additional trouble of the stamp.

The stamp represents another “hazard” in epistolary communication, for it marks a nebulous in-between: the delay between when the letter is written and when it reaches and is read by the recipient. There is the inconvenience, too, of acquiring a stamp, and the lag its absence can generate. Jacques Derrida muses to his lover in The Postcard, “ . . . I went out to buy stamps, and coming back, going back up the stone stairs, I asked myself what we would have done in order to love each other in 1930 in Berlin when, as they say, you needed wheelbarrows full of marks just to buy a stamp.”

Once the stamp is obtained, the indispensable postal worker becomes an interloper, a necessary nuisance. I “would like to address myself, in a straight line, directly, without courier, only to you, but I do not arrive, and that is the worst of it,” writes Derrida. In his story “The Empties,” Jess Row describes the confidence required to send a letter: that our mail, once given over, will reach its intended destination. “She slid the envelopes under the metal lid of the mailbox on her parents’ porch and stared at them for a few moments. Proof of her existence in the world. Proof the world existed. You could count on it: someone was coming to take them away. Proof you would be sent, proof you would arrive.”

The letter on paper is “proof” of our own reality. Stamped and dated, letters and their envelopes provide evidence of a dialogue: the postal markings affirm the letter was sent, its presence in the addressee’s possession that it was received.

With all these hazards built into the non-digital epistolary form, the question must be asked: why write letters now, when we can so easily send our words electronically, blithely and for free, at any moment from the comfort of our WiFi-ed homes? Why submit to the hassle of a trip to the post office and the cost of a stamp? Why trust our intimate words on paper to the vastness of the postal service? Why imbue our words in the first place with the gravity of paper, in a world of digital contact so inclined towards the insistently casual?

For me, at least, writing letters is simply a matter of writing. Row describes his ardent sender of letters as, “A writer only in the sense that she loved having written.” This love of writing that comes only in the past tense is so familiar to me. The handing over of the enveloped letter or postcard to postal worker is its own form of publication, albeit one of a limited audience. And when the letter is received by the one for whom it was intended, it may be activated anew, in its reinterpretation at the hands of the recipient.

*

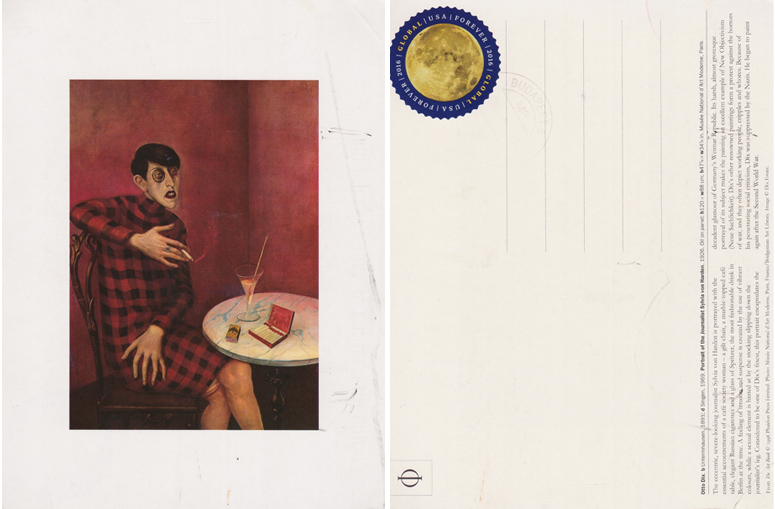

Last autumn, a dear friend sent me a postcard from a trip abroad. On the front of the card was a reproduction of an Otto Dix painting, a portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden. In the painting, von Harden—with cigarette tucked between lean fingers and a flute of alcohol set before her—leans back in a chair that is not keeping up with the times. Its ornate and inutile curlicues seem to me embarrassingly gauche in interwar Berlin, especially in the presence of its occupant: all long lines and sharp angles, the perfect circle of a monocle perched upon one eye complimented by the red and black squares on a straight line dress. Von Harden, with her short, cropped hair and serious expression, appears to be wrapped up in a conversation that is decidedly not about the weather. I was pretty pleased that on seeing this picture on a postcard, my friend thought of me.

I set the image on my windowsill in the bedroom I kept at the time, with the portrait facing into my room. Inside, I looked upon it often, and from outside, by habit leaving each morning I’d gaze up at the back, a white rectangle with circular stamp in dark relief.

I can’t actually say what was written there, though I remember liking it very much upon receipt. Moving again this past May, I picked up the postcard to pack it and made a somewhat frightful discovery: there was no legible text left on the back of von Harden, just a faded trace of the letterforms that once made a message there. The belligerent Texas sun had wiped my friend’s words away. I wrote her a letter to tell her this and offer something of an apology, and she responded (by email) to say that she was alright with this “solar erasure,” found comfort even in the “occasional cosmic correction.” I loved these new words she gave to make meaning of what had happened, and admired her easy acceptance. My loving, but nonetheless careless, placement and the sunrays’ steady shine were not for her a violent intervention on her writing, but a friendly collaboration.

And this feels right, for after all, writing and then sending a letter is at once an act of authorship and a letting go, a willingness to submit to history and the chance inherent in that.

Meghan Forbes

Meghan Forbes writes about modern and contemporary art and literature, makes books, and composts food scraps in Brooklyn.