When I was a child, just before my father left us, he gave me a large doll. She had rather an ugly face and stiff hair you couldn’t brush, but I loved her. I held her in my arms all night and rubbed her plain face with cold cream. One hand was burnt away, black and brown and horrible. Sometimes I thought my mother had had something to do with it. One night I couldn’t find her and lay crying and empty armed in bed, but the next morning there she was, sitting in my chair at the breakfast table. I rushed to put my arms around her but it was a wooden box I was holding, with only her legs, arms and head coming out. The square shoulders were very broad and frightening. I threw her to the ground, then, screaming, tried to hold her in my arms again, splinters scratching me from the rough wood. Besides fright I felt a fearful anger, alternately kicking the poor doll, then touching her with careful hands. Eventually my mother had enough of the “joke” and the doll was banished to the kitchen cupboard. Sometimes I would open the door and look at this Frankenstein monster of a doll with its burnt arm, sitting all square amongst the preserving jars, and weep.

I have few happy memories of my mother. She seemed to blame me for my father’s disappearance. After he left us he used to take me out sometimes. There were jaunts on the river to a great palace, most likely Hampton Court, cinemas and ice-cream far better than any I have eaten since. We went to the sea for the day and a lovely woman came too. She came from another land, but spoke English and afterwards I thought she might have been an American. Then much later I heard that she was a Canadian and that she had died before my father was free to marry her. I always remember that outing, particularly because I never saw my father again. After a day with him mother always asked so many questions. If she didn’t like my answers, she would slap my hands until I cried—not that she hurt me physically, the hurt was mental.

My mother was the games mistress at a local school which I attended. At first the girls teased me and called me “teacher’s pet,” but when they saw how she treated me the teasing ceased. As soon as I was able to cross the busy main road on my own, my mother and I travelled to school separately. It was as if we didn’t want to spend a moment more together than necessary. Strangely enough, she was remarkably generous towards me in some ways. Although her income was small I was well dressed and fed. At Christmas and on my birthday I was given handsome presents as if they were punishments. I remember a new bicycle once and on my tenth birthday there was a real leather attaché case with my initials stamped on it. No one else at school had such a case. They carried their books in bulging satchels on their backs and looked almost humped-backed as they walked. I seldom asked school friends to my home. It was a small, impersonal, Kilburn house with stained glass let into the front door and clinkers in the garden. It was furnished with shabby hire-purchase furniture, fully paid for and now almost worn out. The sofa was made of imitation brown leather and when it was hot it stuck to our bottoms, and the dining-room chairs were the same. The general colour scheme was brown, dark green and browny-gold. The only thing that appealed to me in the house was a French gilt clock which had belonged to my mother’s French grandfather. It gently ticked away the hours on the ugly sitting-room mantelshelf. Sometimes it stopped at eight o’clock, but not often or mother would have thrown it out. There was Robinson Crusoe sitting under a palm tree and Man Friday ministering to him and there may have been a sunshade although it seems unlikely. I think it was this clock that started my interest in antiques. As I grew older I’d spend Saturday mornings searching for antique shops. Although Kilburn was not a good place for them, there were plenty not too far away and there was the Portobello Road street market, which seemed like a strange fairyland to me. I had very little money but occasionally bought Victorian children’s books and headless Staffordshire figures and, on one occasion, a plate to commemorate the birth of King Edward of which I was very proud. My mother suffered the china but later on banned books in case they had “bugs in their spines.”

“We spoke little to each other, my mother and I. She would make remarks like, ‘Really, Bella, you look a perfect guy in those trousers. Your bottom is too fat, so are your hips.'”

I left school at 16 with a few O-levels, few ambitions and few friends. Mother immediately sent me to a business college. I loathed it at the time, but the knowledge I gained there has come in very useful. My first job was in a coal office with bowls of coal displayed in the dusty window. It was called “Crimony, the Coal People” and I typed letters to customers reminding them to order coal before the summer ended and the price went up. There were also invoices and the telephone to answer. The women I worked with were kind but elderly and talked about their knitting machines and their retirement. Should they leave their little flats and move to the coast, Bognor perhaps, or would life in a small private hotel be more convenient? No housework, but what would they do with their time? I listened to their plans but knew it was unlikely they would ever leave their safe little homes, at least as long as their health lasted. They were fond of spring-cleaning and gave a day-to-day account of the cleaning as they did it—how the carpet was sent to the cleaners and the curtains washed, the condensation in the pantry and the surprising amount of dirt they found under the cooker and, horror of horrors, the lavatory pan had a crack. Mr. Crimony wasn’t difficult to work for although he did sometimes follow me into the basement cupboard where the old files were kept. He’d come very close so that I could hear him breathe and perhaps a dark, hairy hand would come on my shoulder, but that was all. I trained myself to be very quick at finding files, though.

I stayed with coal for six months, then to my mother’s dismay went to work in a second-hand furniture shop in Chalk Farm. It was a junk shop really, but occasionally something good appeared, so hopeful dealers came from time to time and I gradually became involved with the antique world.

In the meantime, there was my mother still at the school. Her severe black hair was slightly grey and the slang words she liked to use were a little out of date now and the girls smiled and called her old Winterbottom behind her back. Sometimes she’d have drinks in a popular pub with her fellow teachers, but they never came to the house. I don’t think anyone did.

We spoke little to each other, my mother and I. She would make remarks like, “Really, Bella, you look a perfect guy in those trousers. Your bottom is too fat, so are your hips.”

I’d say, “Good, that’s how I like them,” but I didn’t. I worried a lot about my heavy hips and legs. The top part of me was almost beautiful and still is except for one disfigurement. My black hair is still thick and glossy and falls into lovely shapes whether it is cut short or left to grow long. My eyes are very dark with a kind of glitter, at least they glitter when I see them in the mirror. My skin is fine and white, a healthy white, and my lips are red even without lipstick. I have good teeth too and a good figure now, but in those days, when I was still in my teens, I was heavy below the waist with a largish bottom, rather thick thighs which bulged a bit when I sat down and plump legs that fortunately did taper at my ankles before they reached my small feet.

If I have boasted about my appearance—and I must admit that I used to be rather vain as a girl—I’ve been punished for my vanity and given a disfiguring scar on my left cheek. It used to be nearly three inches long, and lifted one eye in a horrible leer, but now, after treatment, the eye hardly notices and the scar is shorter and no longer purple-red. The stitch marks have almost gone too. At first it was as if I had a fearful centipede running up my face and I covered it with my hand when I spoke to people. I still turn the left side of my face away.

My father called me Bella. The name was an embarrassment at that time.

__________________________________

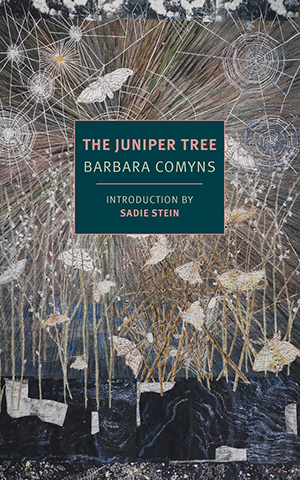

From The Juniper Tree. Used with permission of New York Review Books. Copyright © 2018 by Barbara Comyns.