The Great Hype: When Helga Fooled Us All

Robert Hughes on the Media Frenzy of Andrew Wyeth's "Secret" Helga Paintings

I remember exactly when and where I first heard about the Helga pictures. It was on August 6, 1986, at ten in the morning, and I was picking bugs off my tomatoes at the back of my house on Shelter Island. The telephone rang and I ran inside to answer it. The managing editor of Time, Jason McManus, was on the line.

Jason, who was normally very laid back, sounded uncharacteristically excited. Had I seen the morning’s New York Times? No, I had not. Well, go and have a look at the story on page 1, and call me back. It’s Wyeth.

With a sinking heart I drove down to the island pharmacy and bought the paper. And there, on page 1, was a story by one of its arts reporters, Douglas McGill. It announced that a Pennsylvanian collector named Leonard Andrews had bought 240—two hundred and forty!—previously unknown works by Andrew Wyeth, for an undisclosed sum said by their new owner to be in “the multi-millions of dollars.”

Each of them depicted a woman named Helga, no surname. She was in scores of poses, clothed and nude, inside and out of doors. Among them were four temperas, sixty-seven watercolors, and more than a hundred ink drawings, made over a period of fifteen years between 1970 and 1985. Wyeth, it appeared, had kept them all in the loft of a millhouse on his property at Chadds Ford in Pennsylania. His wife, Betsy, the Times reported, had not known of their existence until 1985, when Wyeth, who feared he might be dying of influenza, told her about them. The announcement was made jointly by their new owner, Mr. Andrews, and the young editor of Art and Antiques, Jeff Schaire. Wyeth, apparently, had hinted to Schaire in the course of an interview a year before that he had a cache of secret drawings and paintings—“But I don’t want them to be seen. There’s an emotion in them that I feel very strongly about. Maybe some day they will be seen, but not until I’m dead.”

Later, the Wyeths had given Schaire permission to run some of them in his magazine, and the issue was about to be published when the announcement of Andrews’s acquisition was made. They were to go on show at the National Gallery in Washington through the summer of 1987. When she was asked what the pictures were all about, Mrs. Wyeth paused significantly and then uttered the magic monosyllable “Love.”

With some foreboding, I rang Jason back. I got him after the morning editorial conference. It was plain that he and the senior editors of Time were in a state of advanced rapture about this story: the secret hoard, the unknown collector, the fifteen-year obsession of America’s uncontested champion pictorial puritan with a mystery blonde, the unknowing wife—the lot. I expressed skepticism about it. It all seemed a little too good to be quite true, and the romance with the blonde struck me as distinctly unlikely. And since it had long been a well-known fact that Betsy Wyeth was her husband’s business manager, the notion of a quarter of a thousand objects squirreled away from her eyes over one-third of their matrimonial life together seemed even less likely.

Plus, I was sure I had seen some of them, somewhere, before.

None of this cut any ice with my editors, who were planning an “inside cover” on Wyeth and Helga. This was a story which, though it would not run on the cover itself, would at least be as long and thorough as a cover story, and as splashily illustrated. Jason wanted me to write it, starting that day.

I refused, mainly because I hadn’t seen the pictures and all my life I have made it an iron rule not to write about any work of art I have not seen. But partly, also, because (I said) this smelled like a hype.

Jason, being a sensible and forgiving editor, was irked but did not press the issue. Our film critic, much to his annoyance–he never really forgave me for dumping this baby on his desk—was delegated to write the Wyeth-Helga story. Phone calls and telegrams started flying off to Chadds Ford and Art and Antiques to secure transparencies of the Helgas.

And meanwhile, over at Newsweek, much the same was happening. Inflamed with the prospects of this saga of human interest, Newsweek looked at the Helga transparencies, upped the ante, and decided to run the story on its cover. By Wednesday Time, having been leaked this news, resolved to call Newsweek’s three jacks with a straight—goddamnit, we would put Helga on our cover too. Never before in their history had an artist made the cover of both Time and Newsweek in the same week. This didn’t even happen to Picasso. In fact it made Andrew Wyeth the only person from the domain of the arts to qualify for the signal honor hitherto reserved for presidents, the Ayatollah Khomeini, and Henry Kissinger in his prime.

Meanwhile the story had got onto the television networks and was being splashed on the front page of every newspaper in America. Nobody wanted to be left out of it, even though, as the week wore on, there seemed to be less and less of it to get into. The lanes and back roads, diners and gas stations and Kmarts of rural Pennsylvania were crawling with intrepid reporters, festooned in tape recorders and videocams, looking for Helga. My colleagues would lean over the diner counter and flash a picture of her, naked as a jaybird. “Know this lady?” Nobody did. The close-mouthed locals would deny all knowledge of the mystery blonde, and even of Andrew Wyeth. Whether Wyeth was obsessed with her or not, the media certainly were. The quest for Helga began to take on the epic proportions of the search for Patty Hearst, or even the Lindbergh baby.

And in due course, she was found, by reporters from the Philadelphia Inquirer and USA Today—Mrs. Helga Testorf, a German émigré aged fifty-four (and in great shape for her age), who, in a way proper to her newfound role as the American Mona Lisa, refused to say anything at all but disappeared behind an angry husband, several hostile kids, and a pair of Doberman Pinschers.

It was reported that Wyeth had been able to paint her without Betsy Wyeth knowing because she had served for a time as nurse and housekeeper to Wyeth’s sister, Carolyn Wyeth, who dwelt in her own house at Chadds Ford. Presumably the creative trysts took place there. But then one learned that this could hardly have been the case, since according to several normally credible witnesses Carolyn Wyeth was, not to put too fine a point on it, not merely eccentric but as mad as a hatter. Her neighbors called her the “Wolf Lady,” a nickname she allegedly earned by keeping a dozen or so large hounds which loped about baying in their grounds while she herself, barefoot and dressed in what appeared to be a modified grain sack, her hair thickly matted, made loud howling noises at passersby from the porch. It seemed unlikely that Wyeth and his model could have got on with the creative act, let alone the amorous one, with this odd sibling vociferating in the next room. None of this could have got into Time—it sounded too much like Cold Comfort Farm to be quite credible—but in any case it reached us too late for the closing deadline.

By Thursday, in fact, the whole story was beginning to look discouragingly thin. On the editorial floor of Time, and probably Newsweek too, haggard journalists were heard imploring God to send a nice little war in the Middle East to bump Helga off the cover. But this was August, a month in which things rarely happen, and the two mighty organs of news and opinion continued majestically to steam toward one another on their collision course, each with Mrs. Testorf, the Simonetta Vespucci of Chadds Ford, affixed like a battle figurehead in full color to its prow. It was too late to turn the wheel, and neither captain expected the other to blink, or was ready to do so himself.

By now it was clear that the original attraction of the story had very little to support it. Nobody had found a trace of evidence to suggest that there had ever been an affair between Wyeth and Helga. If the pictures were about Love, as Mrs. Wyeth had coyly suggested, the love was too generalized to speak its name. Wyeth’s sister, the Wolf Lady, pithily dismissed the romance story as “a bunch of crap.” Worse, there was a gathering suspicion that, far from not knowing about the Helga pictures, Betsy Wyeth knew all about them and owned several. This was confirmed, a week after the two covers of Helga hit the streets, by my colleague Paul Richards of The Washington Post, who traced the history of a number of these “secret” and “unknown” works. One of them, Cape Coat, had been reproduced in Art Gallery Magazine back in 1979. Another, Day Dream (1980), had been bought fresh off the easel by the dreadful Dr. Armand Hammer, who subsequently placed it on view at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, in Peking, in Moscow, Leningrad, and the state gallery in Novosibirsk, in West Palm Beach, in Palm Springs and Cincinnati, four times in Los Angeles, and finally in the National Gallery of Art in Washington as part of a celebration show for President Reagan’s second inaugural in January 1985. If this was a secret or unknown image, few artists would not yearn for an equal obscurity.

And then there was the mystery Maecenas, Leonard Andrews. Obviously the block purchase of 246 Wyeths, along with their reproduction rights, represented quite a commitment for a collector. But Leonard Andrews was not a collector in the normal sense. He was a publisher of newsletters with no earlier or later recorded interest in the visual arts. He had some twenty-five publications, all of a fairly specialized nature—The Swine Flu Claim and Litigation Reporter, The Asbestos Litigation Reporter, The National Bankruptcy Reporter, and so forth. It was quite plain that his purchase of the Helgas and their associated rights was a publishing deal—and a very lucrative one, which portended a great cloning of Helgas in years to come, as reproductions, “rare print” editions of five thousand copies, greeting cards, place mats, and indeed anything else, on any surface that would take and hold four-color ink. When asked about this, the Wyeths were becomingly shy, and Andrews distinctly evasive. Eventually the Helgas ended up in the possession of a Japanese reproduction factory, which seemed to contradict the impression Andrews strove to create—that he only wanted to raise underwriting for something he grandiosely called the National Arts Program. He must have made a fortune, though no one could discover how much, unloading it all on the infatuated Japanese, who in those days were paying clinically insane prices for various kinds of Western art—van Gogh, Renoir, and even Wyeth.

Like the Franklin Mint and the Washington Mint and all those organizations that publish enormous “limited” editions of kewpie dolls and numismatically worthless medallions, the National Arts Program, despite its official-sounding name, had nothing to do with the U.S. Government. (One should note as well that the very words “limited edition” are quite meaningless: all editions are limited, since none can be infinitely large. The question is what the edition may be limited to.) The National Arts Program was merely a term invented by Andrews, to whom it belonged, lock, stock, and barrel. He claimed, however, that the program would release previously unimagined and untapped resources of talent, from amateur artists. “I want,” he told the media, “85 to 90 percent of the country to come forward with their artistic talent to have it judged by professionals. We’ll give scholarships and cash prizes. We’re looking for the indigenous art of America. I believe firmly that everyone has artistic talent, whatever level it’s at.” Though a Republican, he sounded quite like Joan Mondale. It is hard to say whether anyone, including Leonard Andrews, actually believed this airy blathering. Possibly a few people did, since one of the most cherished of American delusions is that everyone can be some kind of artist, and that it is arrant elitism to think otherwise. It is meretricious and pseudotherapeutic rubbish, of course, but one mustn’t say so out loud. Andrews also announced that his National Arts Program, that very week, had sent out twenty-eight thousand invitations to the municipal workers of Philadelphia, inviting them to bring in their artwork to be assessed. There was, however, no response: either he forgot to put stamps on the twenty-eight thousand envelopes or Philadelphia was critically short of Sunday painters. But the patron was undeterred. “I believe,” he announced, “that if you do something, you have to be a little bit ignorant about what you’re doing. I think ignorance is part of success.” In five years, he added—that is, by 1991—the National Arts Program would be functioning in the hundred biggest American cities, and would have become the largest event in the history of American art.

Twenty years have flown by, not just five, and nothing further has been heard of the National Arts Program, or of Leonard Andrews. This was the greatest and perhaps the defining art-world hype of the 1980s. It was beginning to look like that even before the Time and Newsweek covers appeared. But in the meantime a more immediate problem had cropped up, a blond, often wispy, sometimes decorous but nevertheless insoluble problem—Mrs. Testorf’s neat tufts of pubic hair. Genitals, and by extension the nude body itself, have always been a big problem for mass-circulation magazines in America. They are the point where American puritanism, which will not be denied, intersects, with the most perverse and contradictory results, with American libidinousness, which can stand no denial, either. It may not be a problem for Hustler, Playboy, or Penthouse, but for us at Time it was and always has been. You can reproduce the Medici Venus in Time but not a full-frontal Modigliani; Poussin and Rubens present few problems, but Picasso many; and the day is not in sight when the clean weekly family magazine could possibly reproduce that immense and to many people alarming bush, Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World. (On the other hand, it’s difficult to think what circumstances would make it necessary. A cover story strongly oriented to gynecological research?) The same is true of the human penis, although some of the tinier weenies of the Hellenistic gods might slip by. The reason was not so much that editors were offended by sight in painting of what Lord Rochester called “the mossy entrance to the bower of Venus,” as that they feared an organized write-in by Christian fundamentalists protesting the seepage of pornography into Time.

And so it was with Helga. The art department had to keep a vigilant eye out for any stray curls, so that our portfolio of Wyeth’s Helgas gave the impression less of sexual daring than of a moody and glacial chastity.

By the following Tuesday the issue was on the stands at last. As I predicted, the immediate consensus among journalists was that we had been had. We had succumbed to a hype of a size that no one, even in the febrile and exaggerated art world of the late eighties—not Al Taubman and his team of hustlers at Sotheby’s, not Mary Boone or Leo Castelli, not the hot young stars of SoHo, like the now somewhat obsolete Julian Schnabel—had quite managed to equal.

Hype may be defined as the management of disproportion. Disproportion is managed by playing on several themes. First, in this case, the theme of “secrecy” and “hiddenness,” whose subliminal message was “discovery” and “treasure.” Being secret, the Helgas had to be more interesting than other Wyeths which were public. In fact they were not secret, but they were made to seem so; and the skill of the hype lay in persuading the most powerful instruments of publicity in the country—its chief mainstream newspapers, its TV networks, and its two principal newsweeklies—to behave as if they were secret, even in the act of discovering that they were not. The secrecy, the undisclosedness, of Helga was the very core of the story, and so the magazines, once committed, had to show they believed in it even as their own process of reporting showed that it was a lie. So the “exposure” of Helga by the media, in digging her out of her anonymous seclusion in rural Pennsylvania, paralleled and reinforced the supposed drama of her imagined sexual exposure to Andrew Wyeth, the love affair that never was, so cunningly hinted at by Betsy Wyeth. It put the editors of Time and Newsweek in the position of Tarquin, ravisher of Lucretia in Shakespeare’s poem: “Now do I gaze upon thy innocence!”

The second theme, that of “obsession,” played out in two directions: that of Wyeth with his model, and that of Andrews with the paintings.

That Wyeth’s relationship with Helga as model had an obsessive character can hardly be doubted. The obsession of Andrews as collector was a little more problematic. He had to have all the Helgas, just as Wyeth had painted all of them; less than “all” would have been less of a news story. Buying the Helgas was a business move, but to succeed it had to both create a monopoly and come across as an act of disinterested patronage. And for the media to have the story they wanted, both had to be fulfilled. The final lesson of the Helga hype was that we journalists had done it to ourselves. We wanted to believe in a big, squishy human-interest story where none existed. When it began to come clear that there was not, we still went ahead, because we were afraid of being outsplashed by rivals. By the time Paul Richards, in Washington, had shown that the claims that none of the Helgas had been exhibited and that Mrs. Wyeth did not know about them were pure bull, it was too late. So Time made Newsweek do it, and Newsweek made Time do it. We were the losers and the winners were the Wyeths and Leonard Andrews.

There was only one piece of silver lining—a small one. Eighteen months later, in the spring of 1988, when the other best-known Andy in the art world had his posthumous auction of black-mammy cookie jars and art deco toasting forks, and every magazine in America had public-relations people from Sotheby’s swarming over it like blowflies, Time gave the story only one hundred lines, and grudgingly at that.

From The Spectacle of Skill by Robert Hughes. Copyright © 2015 by The Estate of Robert Hughes. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

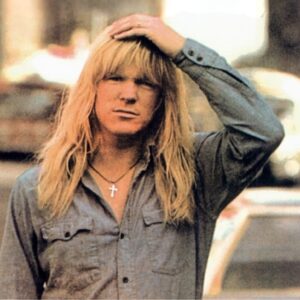

Robert Hughes

Robert Hughes was born in Australia in 1938. In 1970, he moved to the United States to become chief art critic for Time, a position he held until 2001. His books include The Shock of the New, Nothing if Not Critical, The Culture of Complaint, American Visions, Goya, Things I Didn’t Know, and Rome. He is a New York Public Library Literary Lion and was the recipient of a number of literary awards and prizes. He died in 2012.