The Day Virginia Woolf Brought Her Mom Back to Life

May 5th, the Death of Julia Stephen (and the birth of 'To the Lighthouse')

Virginia Woolf’s mom. Why don’t we ever talk about Virginia Woolf’s mom? She doesn’t have a Wikipedia page, and yet she created Virginia Woolf. Her name was Julia. Even though she died in the 1800s—in 1895, when Virginia Woolf was 13 years old—there are amazing photographs of Julia, taken by her aunt, also named Julia, who was a Victorian celebrity photographer, back when “celebrity” meant, like, Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Virginia Woolf’s mom’s given name was Julia Jackson. As a teenager, Julia Jackson played nurse to her ailing mother, who had inflammation but apparently wasn’t so inflamed that she couldn’t travel the world looking for a cure for inflammation. On one of those trips to Venice, Julia met Herbert Duckworth, a handsome man with muttonchops. In short order, they fell in love, she became Julia Duckworth, and they had three children. Before the third had been born, Herbert “stretched to pick a fig” for Julia and died.

That’s how Virginia Woolf puts it in one of her autobiographical essays: “He stretched to pick a fig for my mother; an abscess burst; he died in a few hours.”

If you have any kind of triggers around sudden death, you should not read Virginia Woolf.

So Julia Duckworth was a 24-year-old widow with three children (none of them Virginia Woolf, by the way). Julia was unspeakably distraught. She flung away her religion, becoming “the most positive of disbelievers,” as Virginia later put it, bolstered by the essays in The Fortnightly Review about agnosticism. The Fortnightly Review was founded by Anthony Trollope and edited by George Eliot’s husband. Julia, who spoke French, played the piano, and had an active life of the mind, wanted to talk to the man who was writing these essays about agnosticism—“there was something in his mind that interested her,” as Woolf would put it years later. His name was Leslie Stephen, and it just so happened he was Julia Duckworth’s neighbor. Stephen had taught at Cambridge University, and had been compelled by the school to become an Anglican clergyman, but subsequently he’d been compelled by a trip to America to renounce religion. Woolf describes him in Moments of Being as “a gaunt bearded man who lived up the street.”

One night Julia Duckworth—still grieving over muttonchops’ death, uncertain about the future for her three children, feeling tremendously alone—paid a visit to Leslie Stephen and his wife, Minny (who was William Makepeace Thackeray’s daughter). When Julia Duckworth got to Leslie and Minny’s place, she found them

sitting over the fire together; a happy married pair, with one child in the nursery, and another to be born soon. She sat talking; and then went home, envying them their happiness and comparing it with her own loneliness. Next day Minna died suddenly. And about two years later she married the gaunt bearded widower.

See what I mean about the sudden death?

Anyway, the gaunt bearded widower was Virginia Woolf’s dad.

* * * *

I can’t think of many books—I’m sure they exist, I just haven’t read them—so lit up by a daughter’s intense love for her mother. There are all these books about mothers and daughters being a complicated dynamic (The Liars Club), and all these books about moms who intensely love their daughters (Beloved), but a daughter’s intense, undivided love for Mom? Like so intense it reaches toward infinity? Like an asymptote of love? Are there books like that?

The only one I can think of is To the Lighthouse.

To the Lighthouse is hard to explain. It’s like a black hole made of light. It’s a literary what-the-fuck. It seems so prim and proper but it burns into your eyes. Everything after is stamped with it. For the first 120 pages you think: Wow, this is a dense, vivid, closely narrated afternoon. Then section one ends, and you’re in section two and something seems to have happened to all the characters, they’ve been vacuumed up into that black hole, and this new section sans characters has none of the fullness and ripeness of that character-heavy first section. In this second section, it’s just this antiseptic narrator who’s featureless and eyeless, like the book is now being narrated by a particle of air. I hate this section, it unnerves me, and yet this is the section that everyone reportedly loves, the section that poets teach prose classes about.

It’s missing Virginia Woolf’s mom—that’s what’s so wrong about section two.

It’s thick with descriptions of nature, and inanimate objects like dishes and shawls and sand and saucepans and things like that, but it’s absent of life, absent of Mrs. Ramsay, which is the name Virginia Woolf gave the character based on her mom. In the first section of To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Ramsay is the happy, capable, altruistic, secretly brilliant mom of eight children, just like Julia Stephen was (after she married Leslie, she had four more children, including Virginia), but it’s more than just capaciousness and altruism and secret brilliance that makes Mrs. Ramsay such a wonder. If you haven’t read To the Lighthouse, you’re going to have to take my word for it. (Or you’re going to have to read To the Lighthouse.) There’s something about the way Mrs. Ramsay is rendered that extends beyond the surface of the page. Extends toward the reader…

Mrs. Ramsay doesn’t seem like a fiction so much as a “raised from the dead” fact, “a portrait of mother which is more like her to me than anything I could ever have conceived possible,” Virginia Woolf’s sister said after she read To the Lighthouse.

There’s a surprise that happens halfway between the covers of To the Lighthouse, an unhappy surprise, and I was already unhappy about the sand and saucepans and wind and rain. In passing, while discussing sand and saucepans and wind and rain (and trees and doors and mattresses and wardrobes), Mrs. Ramsay—Mom—is mentioned as having died. The information comes in a subordinate clause of a sentence that’s already weirdly in brackets, as if it doesn’t even belong there, as if it’s a shard of text that’s accidentally sitting in this other thing you’re reading [sorry for the interruption], and the particle-of-air narrator sweeps you away again the moment after Mom is mentioned as having died “suddenly,” and the whole time you’re going: “Hold on, Mom died?!”

But that’s all the information you ever get about mom dying—these two short, odd sentences in brackets. It doesn’t even say how Mom died. Just that it happened “rather suddenly.”

I will never forget the shock it gave me the first time I saw it. I literally put the book down, walked in a circle, picked up the book again, reread the passage, and went: “Are you serious? This is all the information we’re going to get?”

Here’s how Mom dies—keep in mind this is interrupting a page of boring prose about sand and saucepans:

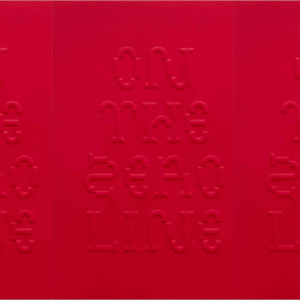

[Mr. Ramsay stumbling along a passage stretched his arms out one dark morning, but, Mrs. Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before, he stretched his arms out. They remained empty.]

And scene. That’s it, that’s all we get. Mom’s dead. Dad’s arms are empty. The very important character, Mrs. Ramsay, the character who made you go, “Whoa, how is this possible?” has just been eliminated. The second half of To the Lighthouse will have to go on without her.

“Damn, I’m supposed to keep reading this now, after you killed off your best character?” I thought as I was reading To the Lighthouse for the first time. “You seriously expect me to just keep going?” After several cycles of emotion—disbelief, discombobulation, grief—a glimmer of admiration crept in, something close to: “Well done, Woolf.” She literally made me disoriented with sadness, and she did it by withholding reason, the way reality itself withholds reason.

For the reader who just can’t imagine keeping on going without that most important character, Woolf’s got you covered: There’s another character who basically brings Mom back to life by thinking about her so hard in the third and final section of the book. In thinking about her this character sees her, and in seeing her we get to see her again, at least as well as any book can let you “see” anyone: Virginia Woolf’s mom, laughing; Virginia Woolf’s mom playing the piano; Virgina Woolf’s mom sitting in the window, knitting, or reading to the kids, or looking at the lighthouse, which is based on an actual lighthouse within view of the house where the family used to summer; Virginia Woolf’s mom eavesdropping on the men and being more capable and cunning and curious than they are, despite their ignorance of her depths.

There’s an enduring mystery about To the Lighthouse, something that sets the book apart, something that isn’t talked about much or fully understood by scholars, a whole other level of disorientation and authorial deviousness vis-a-vis Mom.

Woolf encoded a piece of ungraspable phenomena into her rendering of Mom, like a piece of literary conceptual art or something. You might not notice it if it you come across the text in any other way than I did.

I first read the book in the library at Bennington College, where I’m getting an MFA, and when I flew back to Seattle, I went to Elliott Bay Bookstore to buy a copy for myself, since I couldn’t keep Bennington’s library’s copy. I pulled To the Lighthouse off the shelf and opened to the sentence that had so flipped me out, the sentence where Mrs. Ramsay “suddenly” dies. I just wanted to bask in the brilliance of the death again before buying the book, especially that awkward, leaves-you-hanging “he stretched his arms out.” But “he stretched his arms out” was not in the bookstore’s copy of To the Lighthouse. Mrs. Ramsay’s death was slightly different this time.

It was a different publisher, a different cover, a different typeface, a different everything, including the words and punctuation used to describe Mom’s death. Her death was no less insulting and withholding in this version, but it was different. The two sentences in brackets had been recombined into one sentence, and the leaves-you-hanging hiccup of “he stretched his arms out” was not involved. The difference is subtle, but surprisingly gentler, as if to take your hand consolingly you while you learn about what happened to Mom.

Just like in the other version, the narrator’s talking about sand, saucepans, etc., and then:

[Mr. Ramsay, stumbling along a passage one dark morning, stretched his arms out, but Mrs. Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before, his arms, though stretched out, remained empty.]

Who. The hell. Messes with Woolf. Like that.

That was my first thought. Because that is quite another way to put it. Who? The editor? I flipped open to that page of small type in the front of the book. Who’s responsible for this? Who turned those two sentences into one? Where’s the disorienting quality of the first version I’d read, the almost-looks-like-an-error quality?

I bought this foreign version of To the Lighthouse warily, and in digging around through the scholarship, I found some surprising news, which is that Woolf is the one who messed with Woolf like that.

According to the scholarship, when Woolf got the printer’s proofs for the American edition and the UK edition, the proofs were the same, and Woolf herself marked each up personally, but she marked them up differently. Why Woolf did this “has never been sufficiently explained,” the scholar Julia Briggs says. Moreover, the book never reached a “final” state, or put another way it reached many final states. It was first published (in the UK and America simultaneously) on May 5, 1927, which was exactly 32 years to the day after Woolf’s mother herself died “suddenly” in the morning of May 5, 1895. After To the Lighthouse was published, Woolf continued to live for another 14 years, and as the publisher of the UK edition, she was free to revise it as she liked, and she liked, thank you very much. She liked changing her mind. Three years after the 1927 edition, she published a revised edition in which Mom’s death was handled, yet again, differently. (She added those two commas after “but” and “before,” which hadn’t existed in the first UK edition.) Within three years of the book’s publication, Mom had already died three different ways.

Hans Walter Gabler is a scholar who thinks there are different versions of Mom’s death sentences because Woolf’s “efforts to correct” the passage “did not… fully succeed in mending the phrasing.” That strikes me as borderline condescending. It’s entirely possible that Woolf thought of the passage as vexing and in need of correcting, sure, but that interpretation doesn’t allow for a far more exciting possibility, which is that Woolf intended for the confusion. It doesn’t allow for the possibility that Woolf’s literary reaction to Mom’s dying, in the fullness of time, became: “Mom’s dead? Fine. But I’m going to bring her back in a way that’s as flickering and fluid and ever-changing as any living person.”

The result of Woolf’s syntactical maneuvering is that if you’re looking at the mom in To the Lighthouse from America or the UK, you’re looking at slightly different moms. And if you read about Mom when To the Lighthouse first came out, in 1927, well, by 1930, she had changed a little bit. You think you can trap Mom in words? Nice try.

And to do that while killing her? Amazing.

* * * *

As for Woolf’s experience of that morning in 1895, her emotional reaction to Mom’s sudden death: Any clear information along those lines is withheld from To the Lighthouse. But we can piece together Woolf’s reaction from Woolf’s autobiographical fragments in Moments of Being.

Early in the morning on May 5, 1895, Woolf’s half brother George (his dad was muttonchops, the guy who died picking a fig) led his sister downstairs to kiss mom goodbye. This is clearly the factual, autobiographical ancestor of Mrs. Ramsay dying and Mr. Ramsay staggering with his arms out. Julia had died suddenly of rheumatic fever in the middle of the night. “George took us down to say goodbye,” Woolf writes. “My father staggered from the bedroom as we came. I stretched my arms out to stop him, but he brushed past me, crying out something I could not catch; distraught. And George led me in to kiss my mother, who had just died.”

So the staggering in real life was Dad’s, just like in To the Lighthouse, but the outstretched arms were Virginia’s! The dad with the outstretched arms in To the Lighthouse is alone. But in real life it was Woolf who was alone, ignored by Dad, brushed past. His uncaringness amplified the wound, deepened the shock of Mom’s absence. You assume the emotional inspiration for that grief-striking scene of Dad staggering down the hallway is Dad’s supposed devastation, but plausibly the inspiration was the daughter’s devastation at Dad’s way of dealing with devastation. It’s her arms that were really left hanging.

Woolf was led into the room where her mother’s corpse was on the bed. Kissing her face “was like kissing cold iron,” Woolf writes. “Whenever I touch cold iron the feeling comes back to me—the feeling of my mother’s face, iron cold, and granulated.”

Afterward, Woolf was “obsessed” with her mother. “Until I was in [my] forties”—until she’d written To the Lighthouse—“the presence of my mother obsessed me. I could hear her voice, see her, imagine what she would do or say as I went about my day’s doings. She was one of the invisible presences who after all play so important a part in every life.”

She was shocked by her death, but then again Woolf believed it was her “shock-receiving capacity” that “makes me a writer.” She thought the productive thing to do with a shock was to “make it real by putting it into words. It is only by putting it into words that I make it whole; this wholeness means that it has lost its power to hurt me; it gives me, perhaps because by doing so I take away the pain, a great delight to put the severed parts together.”

Woolf wrote To the Lighthouse very fast, “20 times” faster than any of her other novels. Her husband Leonard read it first and called it her masterpiece. Then E. M. Forster read it and said the same thing. Woolf’s sister said that thing about Woolf having raised Mom “from the dead.”

And once it was written, Woolf noticed, “I ceased to be obsessed by my mother. I no longer hear her voice; I do not see her.” Why? The question haunted Woolf. “Why, because I described her and my feeling for her in that book, should my vision of her and my feeling for her become so much dimmer and weaker? Perhaps one of these days I shall hit on the reason.”

Christopher Frizzelle

Christopher Frizzelle is the editor-in-chief of The Stranger, Seattle’s Pulitzer Prize-winning weekly newspaper. He is a candidate for an MFA at Bennington Writing Seminars.