Ten Books Making News This Week

'Go Set a Watchman' vs. 'Between the World and Me'

Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee

The continuing Harper Lee mania surrounding the July 14 publication date of Go Set a Watchman indicates it is likely to be the most reviewed book of the year. Early reviews revealed the shocking news that the noble Atticus Finch of Lee’s iconic 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird is presented, in Watchman, as a bigot. Many second-round critics emphasized the importance of accepting the flawed, fully human Atticus.

“Though it does not represent Harper Lee’s best work, it does reveal more starkly the complexity of Atticus Finch, her most admired character,” writes Randall Kennedy in the New York Times. “Go Set a Watchman demands that its readers abandon the immature sentimentality ingrained by middle school lessons about the nobility of the white savior and the mesmerizing performance of Gregory Peck in the film adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Stephen Carter’s Bloomberg review, headlined “Go Set a Watchman Is Harper Lee for Grown-ups,” defends Watchman as “a rich and complex story, in many ways more textured than Mockingbird. To make the novel about pinning the right label on Atticus is to miss the point. Watchman isn’t mainly about race. It’s about the process through which protagonist Jean Louise Finch comes to grips with the realization that the father she has worshiped for decades is fallible. The story wouldn’t be interesting if his failings were smaller.”

Donna Seaman (Booklist) found Watchman “a daring, raw, intimate, and incendiary social exposé. A story, perhaps, far too alienating, too candid, and too hot to handle fresh from the typewriter, during that more buttoned-up era.”

“We need this version of Atticus Finch,” writes Carolina De Robertis (San Francisco Chronicle), “the realistic one, the complex one, the one who was not in fact immune to the white supremacist thinking of his time and place.”

Alexander Chee calls Watchman “a novel with an infinitely more complicated moral landscape” than Mockingbird in the Guardian’s “panel” review, while fellow panelist Syreeta McFadden acknowledges “We are all Scout: children disappointed by an idealized version of our parents.”

Howell Raines (Washington Post) defends Harper Lee against a “narrow reading.”

The Mockingbird Atticus was the kind of moderate, educated Southerner sympathetic to the New Deal’s progressive racial attitudes. The second Atticus is another Southern “type”: the erstwhile civic leader driven crazy by the 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregated public schools. History changes us as we move through it, just as Huck Finn came to see Jim as a human being while they drifted down the river. Atticus changed, too, but in a less admirable direction… From a stylistic standpoint, Mockingbird is a polished gem. “Watchman” is a lesser stone of rougher cut, but it deserved publication as it stood when Lee delivered the manuscript to Lippincott in 1957.

Meanwhile, The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik questions the book’s pedigree: “Not since Hemingway’s estate sent down seemingly completed novels from on high, long after the author’s death, has a publisher gone about so coolly exploiting a much loved name with a product of such mysterious provenance.”

Jabari Asim (Publishers Weekly) reconsiders Mockingbird, which he read 40 years ago, from the perspective of each of two sons assigned to read the novel in middle school today:

We found it curious that school districts around the country seem to find it more useful to discuss a quaint tale involving an innocent Negro whose life was considered meaningless in 1935 than to devise a curriculum recognizing that black lives still don’t matter in 2015. Just as significant for me were the questions my son posed upon completing the novel. As it turned out, they were no different from the inquiries I was left with… decades ago. Who was the novel intended for, he wanted to know, and was he honestly expected to like it.

And, in literary CSI mode for the Wall Street Journal, Jan Rybicki and Maciej Eder, two Polish data analysts and literature professors, ran the two texts through an algorithm that searched for signs of heavy editing, frequent rewriting and other influences. They concluded that Harper Lee is “the undisputed author of both novels but suggest that her style as a writer was more consistent in Watchman than Mockingbird.”

Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates

The Atlantic senior editor Ta-Nehisi Coates’s fierce and eloquent letter to his son shared the spotlight with the new Harper Lee this week. (Brooklyn’s Greenlight bookstore made sales of the two a horse race, keeping a running tally.)

“Rife with love, sadness, anger and struggle,” writes Walton Muyumba in Newsday, “Between the World and Me charts a path through the American gauntlet for both the black child who will inevitably walk the world alone and for the black parent who must let that child walk away.”

This follows Toni Morrison’s endorsement (she called the book “required reading” and compared Coates to James Baldwin, which drew a predictable backlash and defense) and early glowing reviews from Michiko Kakutani, who called the book “a searing meditation on what it means to be black in America today,” and Jack Hamilton, whose Slate review announced it as “a major work, a book destined to remain on store shelves, bedside tables, and high school and college syllabi long after its author or any of us have left this Earth” and “a love letter written in a moral emergency, one that Coates exposes with the precision of an autopsy and the force of an exorcism.”

Barbarian Days, William Finnegan

William Finnegan’s surfing memoir impresses Thad Ziolkowski, whose New York Times Book Review critique calls out Finnegan’s rare gifts as masterful writer and surfer. One highlight: Finnegan’s discovery of “the perfect empty wave” in 1978, off a tiny island in Fiji:

The moment of revelation is the surfing equivalent of Keats’s “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer”: “We turned and trained our binoculars on the tiny island across the channel. We were looking straight into the wave… It was a long, tapering—a very long, very precisely tapering—left. The walls were dark gray against a pale gray sea. This was it. The lineup had an unearthly symmetry. Breaking waves peeled so evenly that they looked like still photographs…. This was it. Staring through the binoculars, I forgot to breathe for entire six-wave sets. This, by God, was it.”

Now among the most renowned in the world, the Fijian break is one of perhaps a handful in its class that Finnegan has intimate, masterly knowledge of. Indeed, if the book has a flaw, it lies in the envy helplessly induced in the armchair surf-traveler by so many lusty affairs with waves that are the supermodels of the surf world. Still, Finnegan considerately shows himself paying the price of admission in a few near drownings, and these are among the most electrifying moments in the book.

The Pawnbroker’s Daughter, Maxine Kumin

The Pawnbroker’s Daughter is “a loose and lucid memoir that charts Kumin’s path from a middle-class Jewish kid in Philadelphia to a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet laureate, feminist icon, and, perhaps most significantly, flatlander turned New England farmer,” writes Michael Andor Brodeur (the Boston Globe).

Kumin, who died in February 2014, bought a sprawling place she named PoBiz Farms after she won the 1973 Pulitzer for Up Country. Here, notes Brodeur, she had “space to breathe—and peace to write.”

Kumin’s poems have long dug into the fertile turf of her farm life, and here we see her foraging for fiddleheads and chanterelles, foaling mares, and minding the local population of frogs, woodchucks, and porcupines. Old Harriman Place (the original name of the rural New Hampshire property) “lodged deeper and deeper into our psyches,” she writes. So, too, can it help inform how we experience Kumin’s poetry.

Watching her reawaken the history of the old white farmhouse, with its saggy barn and shaggy acres, feels not unlike reading her poems—making them new just by occupying them, for however long. The longer you stay, the richer they grow, something Kumin saw coming in a poem from 1986 called “A Calling”: “Poetry is like farming. It’s / a calling, it needs constancy, / the deep woods drumming of the grouse, /and long life.”

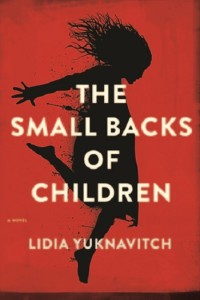

The Small Backs of Children, Lidia Yuknavitch

Steph Cha (Los Angeles Times) describes the opening of Yuknavitch’s “explosive” new novel: “an Eastern European war orphan watches a wolf free itself from a trap by gnawing off its own leg, then squats over the abandoned limb and urinates on the blood and snow” as “an indelible scene that introduces the book’s main themes of art, violence and the body: This is how the sexuality of a girl is formed—an image at a time—against white; taboo, thoughtless, corporeal.”

This is not a conventional work of fiction, Cha writes: “at times things like character development and pacing are sacrificed in favor of broad strokes that are poetic and shocking but a bit circumspect. The central cast is large for such a short book, and few characters get enough exposure that their betrayals and injuries, whether inflicted or received, resonate deeply. While the themes are fascinating and nuanced, the plot ends up feeling like a compilation of extreme actions and events that read like art as provocation.

Which, incidentally, seems to be the point.”

Meanwhile There Are Letters, Suzanne Marrs and Tom Nolan (Eds.)

“Fascinating, delightful, and often heartfelt.” That’s Sarah Weinman’s take (The Guardian) on the correspondence between Eudora Welty and Ken Millar (who wrote as Ross Macdonald) as collected by Suzanne Marrs, Welty’s friend and biographer, and Tom Nolan, Macdonald’s biographer. The two began a correspondence in 1970, when Millar wrote a fan letter to Welty upon the publication of her Losing Battles, and continued with growing intimacy through the next decade.

“Macdonald died in 1983,” Weinman writes, “but not before Welty was able to visit Santa Barbara one final time, clearly agitated and bereft at the loss of his faculties and the imminent end of their literary and personal friendship. For all that Nolan and Marrs tried to spin their connection as something more, perhaps the most convincing note was struck by Welty herself, in the unfinished short story ‘Henry,’ also included in the volume. The titular character, like Macdonald, is ravaged by Alzheimer’s, cared for by his overwhelmed wife Donna, and clearly loved by the narrator: ‘Henry in being so pre-eminently a married man was that much the dearer to me, for of course I knew it was this that made him need me.’”

Death and Mr. Pickwick, Stephen Jarvis

Adam Kirsch (The Christian Science Monitor) calls Death and Mr. Pickwick a “one-of-a-kind debut novel.” In “some 800 leisurely pages, Jarvis unfolds the entire prehistory of The Pickwick Papers, to a depth that even a Dickens scholar would find hard to match.”

And there’s more praise to come:

But the triumph of Pickwick—and Jarvis argues that it was the greatest triumph in English literature, the most popular, recognizable, and widely translated book next to the Bible—all belonged to Dickens. Seymour, who according to Jarvis’s theory invented the story and all the main characters, was muscled out of the project early on by the imperious Dickens, who stopped following the lead of Seymour’s illustrations and instead forced the artist to draw what he had written.

The indignity of this, combined with other financial and sexual problems, is said by Jarvis to have been the cause of Seymour’s suicide, which took place just after the second issue of Pickwick was published. Whether that is the truth or just another story is, of course, impossible to know. But surely there is no one in the world more qualified to tell it than Stephen Jarvis.

Violence All Around, John Sifton

“Inclination leads him to history, philosophy, and literature, not polemic,” The New Yorker’s George Packer writes of John Sifton, “grandson of the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, son of a federal judge and a writer and editor of books,” and a former Human Rights Watch researcher. In analyzing Violence All Around, which covers a spectrum of post-9/11 attacks from beheadings to drone strikes, Packer notes, “It begins with a three-hundred-sixty-degree view of violence, then slowly zeroes in on the C.I.A.’s torture, rendition, and drone programs. Al Qaeda pretty much disappears. The Taliban blur into the general Afghan population… The Islamic State barely rates a mention. These are strange omissions…”

Miss Emily, Nuala O’Connor

Miss Emily “immerses us in the day-to-day drama of a fictional, spirited Irish maid who comes to work for the Dickinsons of Amherst in 1866 and stirs up their reclusive poet-in-residence,” writes Heller McAlpin in The Washington Post. The novel, told in alternating chapters by Dickinson and her maid, “pulls us in from its first limpid lines and then detonates with an explosion of power—much like Emily Dickinson’s poems.”

Visions and Revisions: Coming of Age in the Age of AIDS, Dale Peck

Judy Blunt (New York Times) finds Dale Peck’s memoir—in which he offers “a flinty-eyed look into the heart of the H.I.V. epidemic, from the late 1980s until the development of protease inhibitors and combination therapies in the mid-1990s”—most engaging when it’s “bounding around in Peck’s literary backyard.” Its “edgy experimental feel,” she notes, will neither surprise nor disappoint readers familiar with Peck’s novels. “That the timeline covers what Peck calls his ‘slutty days’ is evidenced from the outset, though readers who are not squeamish about bodily functions or impatient with a young man’s sexual obsessions will find a compelling snapshot of the social activism that defined the era.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.