Squid Eggs, Traffic, Trees, and More: Object Lessons for Earth Day

Four Writers on the Environment and Climate Change

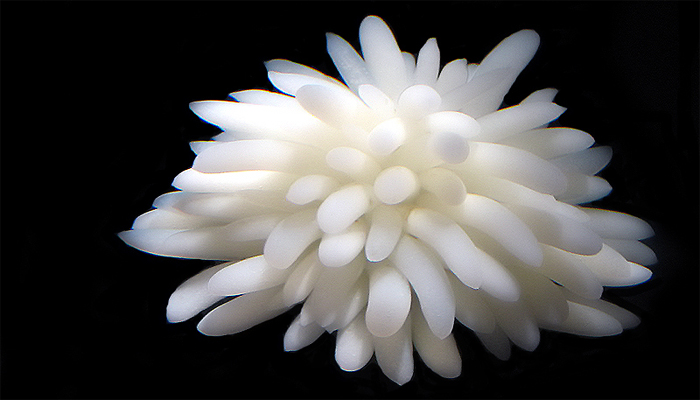

Squid Eggs and Global Warming

The following is adapted from Nicole Walker’s Egg, now available from Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series.

If you were just watching male squid in the ocean tentacling around the ocean floor, punching his fellow male squid in the face, seemingly randomly, you’d think squid were overreacting. But squid are not truculent creatures. They only become obstreperous when they swim over a deposit of egg capsules. Female squid lay egg capsules containing 150-200 eggs. She will mate with many, which is why so many male squid are lying around. But when they’re not mating, just jetting along and they come across a capsule, they are pugilistic. Scientists have discovered the eggs themselves give off a pheromone that triggers the males to act like jealous boyfriends. But unlike jealous boyfriends who often storm off in a snit, these squid, once they’ve pounded the competing male into submission, turn to hug the eggs, protecting them, keeping the other male from claiming they’re his even if these eggs are really some other male squid’s entirely.

Researchers suspect that squid will probably fare well with a slight rise in climate temperatures due to global warming. Squid process their food more quickly in warmer waters. They also grow faster and bigger. Research has not connected aggressive male behavior with temperature, but they do worry about food sources—both that the squid may run out of food sources if the female lays more eggs, if eggs go on to lower juvenile motility and that the eggs and the juveniles may become more a food source as the food sources of the ocean become scarcer.

Can we picture this future so we can sleep better at night? Giant squid, digesting happily, hugging their eggs, protecting their future in the warm baths of an acidic ocean. Or should we pray for them to become delicious treats for the whales who will be hungrier and hungrier as herring and sardines become smaller and smaller. Or should we be worried about aggressive, jealous boyfriend squid, punching hungry humans in the face as we scrape the bottom of oceans, looking for the all-that’s-left-to-eat squid eggs? Somehow, I’m rooting for the egg cuddlers. Humans are not as careful with the fragile as they should be.

Nicole Walker is Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, USA. Her previous books include Canning Peaches for the Apocalypse (2017), Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction (co-edited with Margot Singer, Bloomsbury, 2013), and Quench Your Thirst With Salt, winner of the 2011 Zone 3 nonfiction prize. Her work has appeared in Fence, the Iowa Review, Shenandoah, New American Writing, the Seneca Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere.

Nicole Walker is Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, USA. Her previous books include Canning Peaches for the Apocalypse (2017), Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction (co-edited with Margot Singer, Bloomsbury, 2013), and Quench Your Thirst With Salt, winner of the 2011 Zone 3 nonfiction prize. Her work has appeared in Fence, the Iowa Review, Shenandoah, New American Writing, the Seneca Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere.

* * * *

Expressway to Your Heart

Кто придумал, скажи, эти пробки?

В переулках—зима затаилась

И ждет: что же будет.

Zemfira, “Traffic”

(Who thought up, tell me, these traffic jams? In the alleyways winter awaits us. And we shall wait—what will happen.)

Jammed streets. Smoking exhausts. Lost time. Road rage. A built environment that reflects the needs of the automobile and forgets the most important component in society: children, women, and men who play and work, sit and read, exercise and play music, and stroll and bicycle among us.

In 1967 the Soul Survivors’s hit, “Expressway to Your Heart,” a song that reached number 4 on the Billboard Hot 100, the singer laments “On the expressway to your heart. The expressway is not the best way. At five o’clock it’s much too crowded.” He adds, “I was wrong, baby, I took too long. I got caught in the rush hour.” And yet here we sit, more and more of us, longer and longer, every day on the expressway to work, home, in an emergency to the hospital, to the grocery store, and perhaps to someone’s heart.

Traffic addresses the growing national and international problems connected with automobile congestion in cross-national comparisons of traffic, accidents and safety, and solutions to these problems. I discuss early efforts to deal with traffic and growing safety issues. The former usually involved building more roads and straightening and widening existing ones—the “if you build it, they will come” approach. This led to more traffic, higher speeds, and more deaths and disfiguring injuries. As for safety, until the 1990s most countries, including the world leader in automotive technology, the US, relied on industry-sponsored safety measures—and long delays in rolling them out. And we’ve spent trillions of dollars on automobiles and their infrastructure and wars to secure oil, while crying tears of gasoline when someone suggests better public transportation. At least the Europeans have recognized public transport and bicycles as the way to get to someone’s heart. Or to work.

You know what? We’re number 1! America is great again! LA is first in the world in traffic jams, followed by such cities as Bangkok, Jakarta, Istanbul and Beijing. Traffic, mixed with reference to philosophy and rock and roll, offers solutions, not only criticisms to gridlock and congestion. Americans spend on average 120 hours annually commuting per year. That’s five full days. Just sitting. On that expressway. To your heart.

We continue to focus on the car as if it is a human right, and we’ve equipped the car to be more isolated from social concerns and pollution. New ones have USB ports, Bluetooth connectivity, rearview cameras, and screens. Is the autonomous car the solution? No, first there will always be human error. Second, they are perfect vehicles for terrorist bombers and hackers. Third, they cost about $100,000 per vehicle. What about driving in inclement weather? What if traffic signals fail? The autonomous vehicle represents the foolish tradition of seeking a technological solution to a problem of technological origin. How about safe, inexpensive, proven solutions to put an end to auto carnage and exhaust? How about bicycles in bicycle lanes? Let’s not go the way of the automobile, but away from the automobile. We can use our minds to create obstacles to the automobile, and to disincentivize their use.

Traffic began as a poetic and ontological musing about the speed bump. (“If speed bumps exist, then there must be a higher order of being to help us out of this mess.”) Here are some solutions: signs and fines enforced without remorse; roundabouts and traffic circles; dedicated bicycle and pedestrian ways; heavily subsidized public transportation (it’s much cheaper than building roads, roads, and repairing more roads); neighborhoods made for people not cars; and speed bumps.

Traffic thus is a kind of polemic. I argue that we need to make cities and towns for people, not for automobiles. We need to recognize the huge environmental costs associated with automobiles, the foreign policy dictated by the need for oil, and the decay of existing infrastructure.

Traffic calming (Verkehrsberuhigung) came from German (and Dutch) traffic engineers. There’s probably a direct line from Georg Hegel to the dialects of calming. If Hegel has been in a VW on the Autobahn, he’d likely never had had the time to write Phenomenology of Spirit. And then where would we be?

Paul Josephson is Professor of History at Colby College, USA. He is the author of twelve books, including Fish Sticks, Sports Bras, and Aluminum Cans (2015), The Conquest of the Russian Arctic (2014), Lenin’s Laureate: A Life in Communist Science (2010), Would Trotsky Wear a Bluetooth? Technological Utopianism Under Socialism (2009), and Motorized Obsession: Life, Liberty and the Small Bore Engine (2007). His latest book, Traffic, is now available from Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series.

* * * *

Thinking Like a Species

Joshua Tree National Park

I’ve situated myself atop a mid-size bolder where the Colorado Desert meets the Mojave, where formidable thickets of cholla cactus and the blossom-tufted whips of ocotillo give way to gardens of the tree that gives this national park its name. Not that it’s an “actual tree,” as you’ll quickly be told by rangers in the park—it’s actually a species of yucca, and its trunks and branches are shaggy with the beards of dessicated, blade-like leaves. The Joshua tree is endemic to the Mojave Desert, which extends North from the edge of the Coachella Valley to the Great Basin Desert of Nevada. The Joshua trees know where Mojave gives way to the hotter, drier Colorado, and the cholla know, too—there seems some smart line in the tufted desert earth; the few cholla to its north, and the few Joshua trees that have strayed to its south, seem almost startled when you come upon them, stunned at having been seduced by some microclimate of dune or declivity of rock into germinating so far from the company of kin.

Such lines aren’t enduring, although their transits mostly take place on time scales beyond the human. Geology as much as botany is the great storyteller of Joshua Tree, and the jumbled pillows and dumplings of granite that draw rock climbers to this place tell a story of billowing magma the sculpturing agencies of wind and water shatteringly long in scope. Like all rocks, their forms seem frozen in time—until you realize that these are the forms rock takes in motion, that you’re looking at a dynamism of form, a landscape’s long meditation on entropy—a meditation each turn of which last much longer than any of us can conceive.

Belatedly, we’re discovering that the changes we humans make also churn and compose themselves on longer cycles than any individual human, any collective, any society can reasonably think. The refugium that is the Mojave for the Joshua tree—the tiny patch of Earth’s skin on which these shaggy agave retain purchase—may not outlast the epoch of warming that we have unleashed. And on this Earth Day, on the edge of the blossoming Mojave, I’m wondering how we can move from “thinking globally” to thinking like a species, a rock, a planet.

Matthew Battles is Associate Director of the metaLAB and Fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, USA. His previous publications include Library: an Unquiet History (2004), The Sovereignties of Invention (2012) and Library Beyond the Book (2014). His latest book, Tree, is now available from Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series.

* * * *

Object Earth

The following is adapted from Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Linda T. Elkins-Tanton’s Earth, now available from Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series.

Earth is a home, a limit, and a recurring challenge.

Humans have long struggled with their desire to view the Earth from its outside — as if we could depart the only dwelling we have ever possessed, the place of our birth, and turn back to see that world as a whole. We imagine such a view to be radiant, a revelation, and forget how much it obscures. Only recently has this singular Earth been reduced to one celestial body among billions in a universe indifferent to its splendor and unconvinced of its uniqueness. For a long time we thought the universe revolved around our globe. We now speak of a Copernican Revolution that jarred us away from this anthropocentricity. Yet we remain in some ways deeply Earthbound.

The desire to encompass the Earth through a vision that offers a discrete object, a total picture viewable from its exterior, may be as old as the realization that dreams free us to wander, to create new relations to what we imagine we’ve left behind. Through technology and the imagination we attempt escape the planet’s gravity to attain a comprehensive perspective, looking down from far above, a vision of the Earth denied from its expansive surface. Girdled first by wooden ships and now by urban lights, airplanes and the Internet, the Earth seems to have shrunk into Google Earth, a tamed and domesticated thing, a human commodity rather than a luminous celestial body that defies full knowing. But the image of the Earth as spaceship or marble is still framed from a human point of view. The image leaves much to shadow and obscurity, including the interior. It is easier to reach Mars than our own planet’s core. The Earth is too large, too old, too inaccessible to our senses for us to fully apprehend it all at any one time. We live within the limitations of our human selves, making it difficult for us to contend with global-scale issues and events, like space travel and climate change. We look at images of the Earth and see at once a cosmic globe and a planet we have altered: oceans, flora, fauna, and atmosphere have all felt our heavy hand. Creativity and imagination enable us to push against these limits and disjunctions, though, and perhaps to see ourselves as having enough agency and breadth of vision to face such difficulties of vision, apprehension and action.

Very few humans have ever beheld the Earth in its entirety. Yet as ancient texts attest we have long imagined attaining that perspective, whether in sleep or in death or as an astronaut. We begin this book by acknowledging that a desire to imagine ourselves looking back upon the only home we have ever known as if we were at its outside, gazing at Earth become object, recurs across history. Yearning to behold the planet from some point of view more comprehensive than the fragmented perspectives we possess living along its surface—to see snowy mountains, torrid deserts, and roiled seas resolve into a singular sphere—is an enduring aspiration, and a ceaseless prod to creativity. We imagine ourselves leaving our terrestrial habitation to perceive in one instant its vexing expansiveness, to gain a total picture—to know the Earth, and maybe even to love it.

Earth is a problem. If the Earth is a singular object, how do we observe it? How do we know it? How does knowing the Earth challenge what knowing means in the humanities? In the natural sciences? How do the stories humans have long been telling about the Earth inform and interact with the Earth we apprehend from our expanded technological capabilities? Why do we so ardently desire to be able to look at the Earth as if we no longer stood upon its rough surface? Can technology intensify how we feel about the Earth? How are recent space craft and satellite derived images of the Earth that represent the globe suspended in the immensity space connected to an ages-long impulse to imagine what the Earth looks like when viewed from a great distance? Within such a perspective are we looking back or looking out? Why does the urge to explore drive us away from the only home we have had? Is Earth’s gravity as metaphorical a force as it is physical, and if so can we ever escape that pull? Do we travel into space (through probes or through story) only to discover the past or the future of the Earth? Or to try to discover if we are alone?

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen is Professor of English and Director of GW Medieval and Early Modern Studies Institute at George Washington University, USA. He is the author or editor of 11 books, including Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (2015). Linda T. Elkins-Tanton is Foundation Professor and Director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, USA. She is the author of The Solar System, a six-book series.