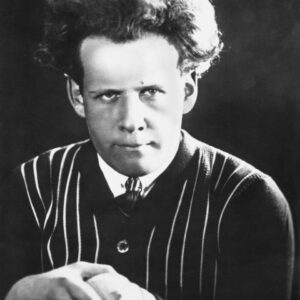

Silence is a Ghost: Jane Wong and Aditi Machado in Conversation

On Grief, Bodies, and a "Poetics of Haunting"

I

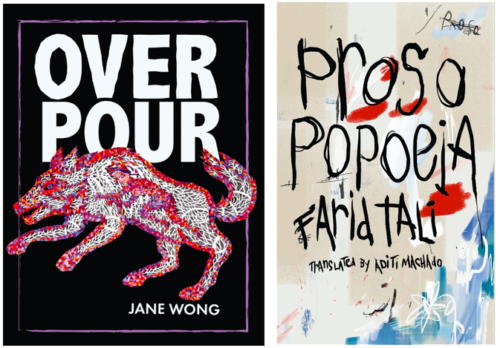

Jane Wong: When I write about a poetics of haunting in my work, I think a lot about how form itself is haunted too. When reading Prosopopoeia, I’m immediately struck by its use of prose poems and non-linearity. Edouard Glissant too, in Poetics of Relation, writes about the importance of form when thinking about the ghosts of colonialism, which reverberates into the present and future. For him, narrative “implode[s] in us in clumps” and we are “transported to fields of oblivions, where we must, with difficulty and pain, put it all back together.” Time moves in multiple directions, right through and above the grave, so to speak. Can you talk a bit about Tali’s use of form as an elegy?

Aditi Machado: Prosopopoeia is narrated by a man whose brother is at times dying and at times already dead from an AIDS-related illness. We keep moving around in time and place and must keep recalibrating to the narrator’s various affective states: rarely mournful, often luridly fascinated, sometimes cold (like the body), sometimes cruel (like a philosopher). Amid these shifting conditions, the prose poems you mention become the most rigorously formal element in the book: they proceed very linearly, describing the putrefaction of the body from head to toe. The poems are baroque, necrophilic, and rather high in register. They were my favorite pieces to translate.

I love that you quote from Glissant, because, even despite the careful methodology of Tali’s faux-scientific anti-autopsy, the corpse is definitely im/exploding through the narrative, creating a mess. Its glamor seeps into the narrative chapters. But also, without giving too much away, the drive to “put it all back together” is also present, toward the end of the book, as the narrator begins to explore, sexually, the live bodies of men. I read Tali’s use of form very much in the context of a crisis of faith and of identity. A belief system can, I think, go a long way in helping one cope with grief, through the forms of mourning it offers (theological explanations, funeral rites, and so on). But if nothing culture or religion offers you works, what’s left? For Tali, I think it is language and the ability to create his own form of mourning through writing.

JW: Like Tali, I find myself obsessed with Prosopopoeia’s focus on the physicality of the body—grieving the body, the corpse, the act of decomposition. I just visited my grandmother’s grave this past weekend and I kept thinking about what her hair was like under the earth, if her jade was still purple around her arm. The book sees death as a process—in its horror and beauty: “Palpable as sound, a perfume of putrefaction spills out into the room. As if one were listening to the swan in the pond dying, which sings as it is dying.” What strikes you about the body in Prosopopoeia?

AM: So many things! Perhaps most obviously, and maybe you feel this too, having thought about your grandmother, that it’s a different kind of curiosity and remembrance, not to think of the endurance of the soul or consciousness, but—illogically or not—that of the body. Putrefaction is so sensuous, the dead body is made gloriously alive.

Less obviously, I’ve begun thinking about just how commonplace the body has become in poetry, literary criticism, philosophy, even pedagogy. Some of this body discourse is riveting, rejuvenating; some of it gives me pause. For example, do we have a tendency to view the body as a stable entity, a truth-telling mechanism akin to what the lyric “I” might once have been considered? I notice this sometimes when people talk about rhythm and prosody: if my body feels it this way, then The Body feels it this way. I’m certain I’ve made the mistake of articulating such statements myself. Translating a book sometimes forces you to dismantle your certainties, and I’ve come to think more about broken bodies, false bodies—the act of dismantling itself, via Tali’s description of decomposition, feels so full of possibility. I’ve also just begun Monique Wittig’s The Lesbian Body (trans. David Le Vay), which the amazing translator-poet Nathanaël brought to my attention, in connection with Tali. In this book, Wittig performs a textual autopsy of the female body in order to celebrate it, affirm it, figure it as powerful. This (to me) new way of writing/destroying the body that recovers agency, passion, language (but not stability or “truth”), I find very provocative.

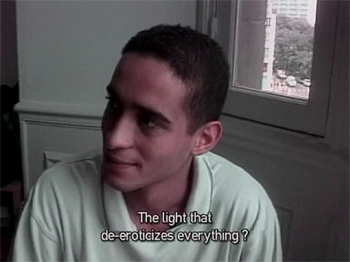

Farid Tali in a still from the film The Road to Love (2001)

Farid Tali in a still from the film The Road to Love (2001)

JW: You write in your afterword that the narrator, F. seeks to watch his brother’s body decompose and “although he probably did make this visit, I don’t see how he could have stayed long enough to watch the body actually decompose. And anyway, the description is hardly scientific. It is unrealistic but moving.” Indeed, as you note, prosopopoeia is the rhetorical device by which to make an imaginary person speak. I love how powerful imagination can be. It can resurrect. In many ways, invocation and dreaming up decomposition is more real than reality itself. In elegies—both personal and communal, how do you envision the transformative power of poetry and imagination?

AM: I’m usually suspicious of the idea that imagination alone, or language alone, can transform anything. But when there is transformation, or something like it, I wonder if it’s because the conditions under which speech occurs have been made exceedingly artificial or been damaged somehow. I don’t trust plain speaking, in general and in poetry, unless it’s an obviously manufactured sort of plain speaking. In other words, I think it’s very important that prosopopoeia is this old Greek thing that Tali wants to announce up front. The Princeton Encyclopedia notes that unlike anaphora, which marks a turning away, prosopopoeia implies the possibility of reply. What’s powerful here is the device’s ability to sustain a gaze into death-as-material, which puts living and dead on equal terms. Different kinds of elegiac forms deal with death, or the deceased one, differently, but always I think with some kind of rhetorical edge. When mourners wail or keen, isn’t that edge the falling from articulacy into noise? I probably shouldn’t say anything general about elegy, since that word can mean so many different things, but I like to think that its tendency is to collect people, dead or alive, to itself, and that because of this the elegy is almost always counter-convention, celebratory.

JW: I was struck by your afterword at the end of Prosopopoeia and how you wrote about the intimate process of translation. Though I’m not a translator myself (and have strange feelings about what I call my “baby” Cantonese), I can’t stop reading pieces about translation like your afterword essay and Don Mee Choi’s “Darkness—Translation—Migration.” In yours, you write about the intimacy of translation and “the ego” of connection: “Because ‘the state of full decomposition’ to which I felt I was bringing the text in my crib is more precisely the rhetorical state to which the narrator brings his dead brother: bits of putrefying yet glorious mess, utterly unlike a composed human body when it is alive.” Can you speak about what you wanted to accomplish through this afterword? Any suggestions for essays on translation you keep coming back to?

AM: Well, I almost failed at the afterword by not writing it, but Joyelle and Johannes at Action Books are too brilliant as editors/translation advocates to let that happen. Actually, I’ve spent a good bit of my PhD study time reading various translation theories and craft statements. Among the many things I love about them are: (1) their sense of language (sing.) and of languages (in their gorgeous plurality) as impossible, capacious, and ultimately weird, a sense that often comes through micro-examples of how something was translated by one or several people; (2) their discussions of ego and subjectivity during the work of translation—I have a preference for conceits that acknowledge the translator’s agency in some way, even or especially if it’s a compromised agency, but the wide range of metaphors available—translator as humble servant, medium, ghost (oh yes), dancer, traitor; translation as pollution, wound, journey—is itself encouraging, and instructive of the contexts that catalyze or enforce them; and (3) their capacity to open the “lonely” “literary” “minor” activity of translation onto the fields of history, ideology, politics, philosophy, desire—Don Mee Choi’s essay is a great example of this. I think I hoped to achieve a little of such things, but mostly to introduce Farid Tali to an Anglophone readership, as he has never been translated into English before.

I will probably miss some important texts but here are some to which I often return: Rosmarie Waldrop’s Lavish Absence; Nathanaël’s “Hatred of Translation“; Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator”; Joyelle McSweeney and Johannes Göransson’s Deformation Zone: On Translation; Anne Carson’s “Variations on the Right to Remain Silent”; A.K. Ramanujan’s “Three Hundred Rāmāyanas.” The nerdy part of me also loves Lawrence Venuti’s books and anthologies, and George Steiner’s After Babel, as ways to begin thinking about translation and language historically, rather than simply accept one person’s concept over another’s.

JW: In your own creative work, in what ways does haunting, elegy, and/or transtemporality inform your work? I’m thinking of lines like “I think a line into the future / but on the sidelines history is / pressed along its pleats” from “Il y a un futur. Le futur passe.”

AW: I don’t know that I have the most coherent thoughts on this, but I’ll try. It’ll sound silly, but it’s amazing to me just how time-drenched English is (also French, which quite possibly has more tenses than English), how we can discriminate between such microstrata of time, between past and perfect past and conditional futures. I am entirely with Steiner when he rhapsodizes over the future tense in After Babel, making statements like “The provision of concepts and speech acts embodying the future is as indispensable to the preservation and evolution of our specific humanity as is that of dreams to the economy of the brain” and offering many a tantalizing example of tense usage: “Reportedly, the Old Believers in Russia, seeking martyrdom and immediate ascent into the kingdom of God, used the future tense of verbs sparingly, if at all.” The time function of language is pretty ordinary, but I like for it to seem extraordinary in poems. That the future can become present or pass quickly into the past. Also, I want to counter nostalgia, uncomplicated nostalgia, of which there is always too much in poetry.

II

AM: I read the title page of your new book Overpour as a concrete poem: the way four letters sit precisely above another four, the doubling of the R’s, the two O’s forming a diagonal, the V softening into a U, which even makes E and P seem like twin letters . . . On the one hand, a visual tightness; on the other, this wonderful metamorphosing, a humming, a proliferation of possibilities. And, of course, in the poems, there is much overpouring, multiplying, blossoming. I love this image: “Under / a microscope, bacteria blooms readily, tiny mansions / of the self.” Could you talk a little about these tropes of excess, of spilling over?

JW: Andrew Shuta, who designed the book, did such a fantastic job translating that feeling of spilling over in the visual impact of the title—including the subtle trembling of the lettering in “OVER.”

And yes, I’m a bit obsessed with (and afraid of) excess, spillage, and being overwhelmed. I’m curious about what happens when we no longer able to hold in that which shames or embarrasses us. I suppose excess itself is quite unheimlich. The tension between containment and spillage is strange to me and I find that I rest in that uneasy space. Growing up, I never saw my mother cry, not once; I was always troubled by that fact. Why would she keep her feelings inside like that? My brother excessively cried in public. He would sit down in the middle of a crowded Jersey mall and turn into a writhing, muddy ball of tears and snot. His snot would run onto the ground and we’d have to cover it with napkins stolen from the food court. Then he would cry harder because he was embarrassed and there was simply no way to stop it until he fell asleep right on the linoleum floor. My mother, though she did not believe in the excess of tears, overpoured in different ways. Frequently, she would buy clothes, feel guilty, and hide them in large Chinese vases, under the fish tank, in suitcases, etc. I’d find clothing spilling over in unexpected places, these bright, new reminders of what we loathe to love. I think about all that stuff. How much blood there is in a cow. How the garbage bin is too full and how you can feel that in your belly. I’m easily overwhelmed by everything – the news, especially. It’s simply too much. There’s horror in the blooming too. And somehow we’re expected to keep calm, to think logically, to not “cause a scene”?

AM: “Sometimes, I think: can Walden exist in China?”—this line, from your poem “Pastoral Power,” is so provocative. I’ve been given to think that, traditionally, the pastoral form operates through binaries like city/country, civilization/barbarism, history/timelessness, in order to arrive at mostly humanist values. But your pastoral deals with migration and debt culture; it challenges humanism by making nature powerful, uncontrollable. Would you agree—and/or what does Walden mean to you here?

JW: I think you’re right about the constant desire to place the pastoral into binaries. Yet, I see the natural world as monstrously malleable. We have a vision of “nature” as that which is untouched, simplistic, and utterly breathtaking; I heard this a lot when travelling around China (especially Western tourists who wanted to see first-hand the “rural, peasant” vistas in Chinese landscape paintings). But there is no such thing. Sure, there are misty mountains in my mother’s home village, but there’s also that guy electrocuting a fish in front of you and talking on his cell phone. The natural world adapts too, as in this video:

I think about that later, in a poem called “Ceremony,” where wolves flourish in Chernobyl. I think about butterflies in chip bags, about geese in parking lots, about the homes we make as a result of migration and adaptation. Thoreau’s assertion that he “went to the woods because [he] wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life” is absurd to me. Tourists visiting Guilin and similar village areas seek something they can not find; meanwhile, people like my mother seek to leave such “essential facts of life.”

AM: Between your poetics of haunting, which seeks to go toward the spectral contexts of “migration and collective trauma” in which Asian American poets write, and my translation of Farid Tali’s Prosopopoeia, which features a decomposing corpse, we have two compelling figures of death. I’m wondering how to think about the ghost and the corpse in relation to each another: are they two faces of the same concept? Or are they oppositional? Does the ghost connote absent matter against the corpse’s decaying matter? What do you think? (I ask this partly because of the intense materials and processes evoked in your poems: carrion, mold, insects, food being prepared, things rotting . . . )

JW: Great question about the ghost and the corpse. I think they are quite intertwined—the corpse offers that physicality, whereas the ghost seems a bit more ineffable. With my missing family members who starved during the Great Leap Forward, I can not visit their graves, their physical bodies. They exist as ghosts for me—a kind of presence that it always there, across distances and spaces of time. Like Tali, I am interested in what decay can show me too—and how it is also a way to hold onto something longer. As you write in your response to me, “Putrefaction is so sensuous, the dead body is made gloriously alive.” The sensuousness of rotting meat, of mold, of blood-smeared insects attracts me because it is on the verge of moving into another ghostly world. I have this desperate desire to ask these decaying things how they feel. What grows in there? I want to honor decay as much as I want to honor ghosts. Honor tends to come in the form of vigilance for me. To watch and see is to honor.

AM: If it is not too difficult, could you name some ghosts that/who haunt Overpour and any new/forthcoming projects? One of them seemed to be China’s Great Leap Forward and the devastating famine it caused (which you describe in your wonderful TEDx talk)—I couldn’t help but have that history in mind as I read about mushrooms and potatoes and chickens in your poems.

JW: I think a great deal about agency and power when moving toward ghosts—rather than a burden or return of the repressed. In this way, yes, there is difficulty, but there is productivity in that difficulty. In my forthcoming project, I am writing a series addressing my missing family members during the Great Leap Forward (poems entitled “When You Died“). I do not know their names; I wish I new their names. I wish my family could talk about what happened during that time, but they do not. Silence itself is a ghost. The same goes for the Cultural Revolution. Again, thinking back to excess, I’m curious about what we decide to keep in and what we decide to hide. I am afraid of asking my grandfather about his parents and siblings and what happened to them. I’d rather not ask; yet, I can write to them. I can practice invocation. I can make linkages—from starvation to my mother who could only afford to eat meat once a week to my own gluttony growing up in a restaurant. My family’s ghosts move around me. I also think about recent ghosts—of my grandparents in particular who raised me. I think about how no one told my grandmother that her husband had died, how she was pruning a tree when the procession drove by. My uncles told me that she had dementia and that she didn’t need to know; it would hurt her too much.

AM: In your TEDx talk, you also offer this idea that “a poetics of haunting . . . creates a strong community,” which comes wonderfully alive through your archive of various poets’ work and their artistic statements. It seems like one way in which scholarship can build relationships outside of itself, be open, inclusive, energetic, relevant . . . For those of us who “belong,” in whatever fraught manner, to academia, do you have any thoughts about conceptualizing more projects in this vein or resisting the dehumanizing aspects of our institutions in smaller ways?

JW: Resisting the dehumanizing aspects of institutions, yes! As a scholar, I feel deeply uneasy about the separation between the academy and the communities we are a part of. Perhaps being a poet who believes in messy excess changes my understanding of scholarship. I wanted the digital project to be easily accessible, to inspire other people to look into their own histories and honor their ghosts in whatever ways they see fit. I didn’t want my dissertation to sit there as a monograph. The project is deeply personal too. The poets included in the project are my friends; these conversations were a means to deepen our connection as poets even more. More than anything, I hope that more public and digital projects raise critical questions on more imitate, personal level. I’d like to see scholarly work that celebrates awareness, vulnerability, and the sparks of connection that naturally arise.