Seeking Refuge in Vinyl Records During China's Cultural Revolution

And the Bootleg Paganini Record That Instigated a Bloody Brawl

Around the beginning of the 1960s, our father spent 400 RMB to buy a Peony radio-record player. The record player, in particular, was quite high-tech back then: four-speed selection with automatic stopping coupled with a speed-detection regulation system. I imagined the flood of music that would flow out of the tiny red-and-green power light, turning our lives totally transparent, as if we lived inside a glass house.

Father, however, didn’t particularly understand music, his purchase, while linked with an infatuation with modern technology, was more a reflection of his romantic temperament, a sharp contrast to the ominous age taking shape around us. An age when people endured constant hunger and busied themselves just trying to scrape by, living hand to mouth—idle ears seemed superfluous. Father also bought a few vinyl records, including The Blue Danube by Johann Strauss. I remember after the Peony was first set up, Father leaping about, dancing along to the waltz, almost making me choke with shock.

On the 33⅓-rpm album cover, Russian text printed across an image of the Danube seemed to indicate a performance by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra. My illuminating initiation into Western classical music made me feel like a child tasting his first piece of candy. Many years later when I visited Vienna, Strauss’s waltz mingled with an Austrian pastry, causing my stomach to perform a somersault.

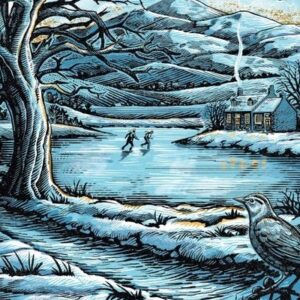

The Cultural Revolution arrived. I’m not sure why but that hurricane now reminds me of those black vinyl records. The epoch had shifted—it was the mouth’s turn to be idle while the ears cocked at attention. I positioned a loudspeaker outside a closed window, lowered the volume, and played my favorite record.

Sometime in early 1969, my friend Da Li, who had been a year ahead of me in high school, borrowed The Blue Danube and took it with him on his move to Hetao Prefecture in Inner Mongolia, where the Great Bend of the Yellow River flows at the foot of Daqing Mountain. In autumn of the same year, I went to visit my little brother at the Construction Corps site on the Mongolian border and, on my return to the capital, I hopped on a train at Tuzuo Banner to pay a visit to Da Li and other former classmates, staying in their village for two days. They materialized as a group at sunset, each carrying a hoe over their shoulders, waists tied with grass rope, a raucous pack of happy chatter and laughter. Upon returning to the Educated Youth commune, Da Li put on The Blue Danube. The graceful melodies of the Austrio-Hungarian nobility melded with the choking clouds of cigarette smoke, rising up to the roof beams of a farmhouse on the northern borders of China.

Years later, Da Li returned to Beijing, but that record album disappeared without a trace.

The second record I remember listening to was Tchaikovsky’s Capriccio Italien, a Columbia 78 rpm Bakelite recording. At the start of 1970, Yifan, Kang Cheng, and other comrades, gathered at my family’s apartment, as if huddling around a bonfire with our backs turned against the cold wind. In that salon raised to books and music, there was a taste of the forbidden fruit of happiness, there were girls who brought their romantic affections. That was when we started to write, each of us an author doubling as a reader-critic. The melodies of the Capriccio Italien must have infused these early writings, as we listened to it more than a thousand times.

It quickly became a kind of ceremonial ritual: hang up some heavy curtains, fill up the wine cups, light up the smokes, let the music carry us along as it broke through the night’s tight besiegement and advanced into the faraway distance. We listened to the record so much that the needle soon needed to pass through the noisy static zone of the dust-filled world before it could enter the splendor of the theme. Then a brief pause. Kang Cheng’s hand gestures established his tone as he began to expound on the second movement: “As dawn breaks into brilliance, a small band of travelers walk through the ruins of ancient Rome. . . .” Deep in the night, the song ended but no one dispersed, each toppling over here and there to sleep, the needle lingering on the music’s coda zhi la zhi la zhi la spinning on and on.

Yifan developed his own photographs at home. One time the red safelight of his darkroom was reported to be a military spy signal; the police went to investigate and, sadly, they confiscated his vinyl records, including the Capriccio Italien. That small band of travelers had crossed into the archive of the dark night to never emerge again.

Album number three: Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 4, a 33⅓-rpm Deutsche Gramophon recording, given to me by my uncle Gufu, the husband of my father’s sister, upon his return from performing abroad. He played the flute in the Central Philharmonic Orchestra, and only retired a few years ago.

“In our cultural salon, material possessions belonged to everyone, the question of borrowing or not borrowing simply didn’t exist.”

Talking about his musical tour through Europe, Gufu couldn’t help but joyfully clap and kick up his heels. While in Vienna, he witnessed a Manchurian manifesting cloak performance that took the city by storm. From within the long cloak and robes the magician wore under a magua horse-riding jacket, he conjured up fire pans, doves, flowers, colorful streamers on the open stage; and for his final inspired act, somersaulted to the side and manifested a giant Beijing opera drum. After a hushed moment of silence, the audience broke out in thunderous applause. This amusing little anecdote, due to its countless retellings and a displaced cognitive association, caused me to conflate Paganini’s record with a Manchurian manifesting cloak, as if it too was part of the magic act.

During the Cultural Revolution, Gufu was sent to a May Seventh Cadre School; I often worried about those wonderful records of his, especially the Paganini, its cover wondrously labeled with “Stereophonic Sound,” filling us with awe—no household could own any stereo equipment at the time. The acoustics of monophonic sound, no doubt, shaped our monophonic ears, and monophonic ears constituted our unique way of listening attentively to the world. Whenever I borrowed an album, Gufu would eye me with suspicion and warn me again: For the ten millionth time, don’t lend it to anyone.

Recalling our initial listening experience of Paganini, it caused a bit of a feverish obsession in everyone. Kang Cheng taught himself German and word for word, sentence by sentence, translated the liner notes on the LP cover for us. When that rousing Sturm und Drang theme resounded bold and unrestrained, he waved his arms as if conducting the strings with the rest of the orchestra. “Just like a bird in the wind, rushing into the open sky, rising to new heights, then falling, and yet unyielding, unwavering, it rises higher, and rises still higher.”

In our cultural salon, material possessions belonged to everyone, the question of borrowing or not borrowing simply didn’t exist. It stands to reason then that Kang Cheng packed the Paganini album into his book bag and pedaled back home with it. One early morning, I arrived at the Ministry of Railways residential apartments on North Altar of the Moon Street. I looked up at the second-floor window where Kang Cheng and his brother lived and observed the figure of a policeman moving back and forth. Trouble electrified the air—my forehead beaded with sweat, chills ran down my back. I immediately sped off to inform Yifan and the rest of our friends, and we converged en masse to plan our counterattack. We first wrote out every possibility of what could have gone wrong, detailing a variety of conjectures plus countermeasures for the right response to any given scenario. The summer of 1970 had just begun and that day felt like it would never end.

Then, as night fell, Kang Cheng mysteriously appeared at my home wearing a dust mask.

It turned out that Paganini had caused all the trouble. So-and-so, a girl at the secondary school affiliated with the Normal University, and so-and-so, her boyfriend, the son of a cadre officer, had brought the exact same record to their own literary salon and it had disappeared. They heard from so-and-so that he had seen it at Kang Cheng’s place and assumed Kang Cheng must have stolen it. One morning before dawn, the strangers appeared at his door wielding some crude weapons. As Kang Cheng’s paternal grandmother opened the door, they pushed her aside and rushed inside, the two brothers still fast asleep in their room. A dousing of soy sauce and vinegar led to a close-quartered fisticuffs.

A “little feet investigation squad” instantly reported the incident and the police appeared at the crime scene, ignoring the black-and-white and whatever red-or-green-between in the situation, arresting everyone first to ask questions later. Paganini, though, couldn’t be held as the chief counter-revolutionary, and so the intruders spent several days in jail for “disturbing law and order,” where they wrote the compulsory self-criticism report, and that was the end of it.

Paganini could never have imagined that his music would circulate in such an extraordinary physical form of preservation and reproduction, circulate, moreover, into such a tangled situation: Almost half a century after his death, halfway across the world, it would be the cause of a bloody brawl between some random Chinese boys. Even more inconceivable is that these two identical vinyl recordings, through whatever unknown channels, found their way into a completely sealed-up China, each mingling, to further the mystery, with the warm blood of youth caught up in two separate underground salons, to eventually meet in a final confluence. Indeed, this all had something to do with magic.

__________________________________

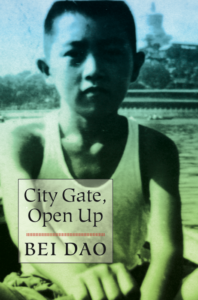

From City Gate, Open Up. Used with permission of New Directions. Copyright 2017 by Bei Dao. Translation copyright © 2017 by Jeffrey Yang.

Bei Dao

Bei Dao, born in Beijing in 1949, has traveled and lectured around the world. He has received numerous international awards for his poetry, and is an honorary member of The American Academy of Arts and Letters. He is currently Professor of Humanities in the Center for East Asian Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.