Pursuing the Artfully Naked “I”: The Myth-Making of Kathy Acker

Seeking the Iconic Status of Great Writer as Countercultural Hero

The trauma of the disappeared father is a theme Kathy Acker pursued throughout her writing, from The Childlike Life to her last published novel, Pussy, King of the Pirates. In The Childlike Life,

My mother tells me my “father” isn’t my real father: my real father left her when she was three months pregnant and wanted nothing to do with me, ever. This husband has adopted me. That’s all she tells me.

The story is told exclusively from the daughter’s point of view in all its many iterations. But then again, perhaps the greatest strength and weakness in all of Acker’s writing lies in its exclusion of all viewpoints except for that of the narrator. As William Burroughs wrote, with great precision, in his blurb for Grove Press’s 1983 publication of Great Expectations, “Acker gives her work the power to mirror the reader’s soul.”

How does she do this? Acker had no shortage of female contemporary writers throughout the 1970s. Outside the downtown New York scene, Jayne Anne Phillips, Margaret Atwood, Ann Beattie, Alice Munro, Janet Frame, and dozens of others published semiautobiographical novels with strong female narrators. But, shaped by their interactions with others in naturalistically described situations, the presence of their narrators was wholly relational. While these women were widely respected for their achievements as writers, they never sought or attained the iconic status of Great Writer as Countercultural Hero that Acker desperately craved. Until she achieved it, no woman had.

In Great Expectations, Acker worked deeply under the influence of such Beat-era icons as William S. Burroughs and Alexander Trocchi and the French modernist writers and thinkers Georges Bataille and Pierre Guyotat. Sometimes described as “philosopher-artists,” these writers conveyed their narrators’ internal lives with startling primacy. And so, by extension, whatever pain and emotion they felt was not theirs alone. They offered themselves as receivers for cosmological information transmitted via their works. “In my writing I am acting as a map-maker, an explorer of psychic areas,” William S. Burroughs wrote.

Defending his work at the 1962 Edinburgh Writers’ Conference, Trocchi proclaimed himself “a cosmonaut of inner space.” Written against history and time, Trocchi’s 1960 novel Cain’s Book dispassionately records a few months in his life as a remorseless heroin addict. His narrator states, “When I write I have trouble with my tenses. Where I was tomorrow is where I am today, where I would be yesterday. I have a horror of committing fraud.”

A special issue of Sylvère Lotringer’s journal Semiotext(e) devoted to Georges Bataille appeared in 1976, and Harry Mathews’s translation of Batailles’s 1928 classic Blue of Noon came out with Urizen Books the following year. Acker and Lotringer were close friends and lovers between 1977 and 1980. Years later, she would credit him widely for introducing her to French theory and “giving her a new language” through which to explain her existential and literary sense of fragmentation, multiplicity, and disjunction. Lotringer taught Georges Bataille in his Columbia University “Sex and Literature” graduate seminar; no doubt he and Acker discussed Bataille’s work and thought.

The first line of Bataille’s Story of the Eye could easily have been written by Acker herself: “I grew up very much alone, and as far as I recall I was frightened of anything sexual.” I don’t write to express anything, she’d write in a 1979 self-interview in the French literary magazine Dirty, named after the “Dirty” character in Bataille’s Blue of Noon. Everything is material. . . culture is more and more a rag-bag. . . I use material that is commonly described as “autobiography.” There are lots of emotions to draw from, and I love working with emotion because I love shock. Acker was the first female writer to so relentlessly pursue the artfully naked “I” of French modernism. In fact, she’d go on to “plagarize” Bataille in Great Expectations:

I never wanted you, my mother told me often. It was the war. She hadn’t known poverty or hardship: her family had been very wealthy. . . My father, a wealthier man than my mother, walked out on her when he found out she was pregnant. . .

The story of the missing father is retold at least three times within Great Expectation’s 122 pages. In a “political” faux diatribe about the Trilateral Commission, she writes,

Three different power groups: the owners of the North-Eastern banks, the top-ranking military, and the Southern oil producers and distributors control the American government. The female artist doesn’t know who her father is. Three months before she was born her father had abandoned her mother. . .

In therapy with the Marin County past-lives regressionist Georgina Ritchie during the last months of her life, Acker embraced the suggestion that her mother unsuccessfully tried to abort her two months before she was born:

George: When you were seven months in the womb, your mother tried to abort you using something to do with heat, a method common in those days.

Electra: I know this.

George: The abortion didn’t work because you were meant to be born. . .

Was this metaphor or memory? Transformed into myth, the facts of Acker’s childhood shift slightly throughout her writings. Sometimes the story is told through the veil of plagiarized texts. Nevertheless, her birth father’s disappearance will haunt her writing for the rest of her life. Since I never knew you, every man I fuck is you. Daddy, her narrator O states in Pussy, King of the Pirates. Still, from at least age twenty-six, when she discussed and transferred the myth of the disappeared father onto the less-than-willing Alan Sondheim in Blue Tape, Acker knew her father’s full name, his address, and his place of employment. Clearly, she made a decision not to contact him, but this decision is absent from all her work.

__________________________________

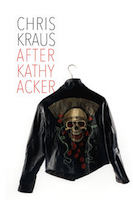

From After Kathy Acker by Chris Kraus, courtesy of Semiotext(e). Copyright Chris Kraus, 2017.