Poetry Needs a Revolution That Goes Beyond Style

From the Introduction to Best American Experimental Writing 2016

America is an experiment.

Thomas Jefferson thought that there needed to be a rebellion against the existing government every 20 years, even if, as he recognized, some of those rebellions were fueled more by ignorance than a desire for liberty. During this election year, we may well ask if all rebellions are equally valued, but every generation certainly needs a revolution of the word. The initial rebellions of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, the Black Arts Movement, and Hip Hop are already two generations behind us. Since that time, American poetry’s mainstreams have absorbed some of the stylistic manners of these movements but not the burning desire for unpredictability, development, and change. What the mainstreams have absorbed is some of the technique but not the motivation. A style that was cutting edge 20 years ago isn’t going to cut it now. A style that is cutting edge right now won’t be so for long.

Art isn’t easy. It’s not just that we need a revolution in style but also a revolution in audience, distribution, circulation, performance, perception and, indeed, motivation. These revolutions are never a question of being marked as ahead of the times—that is the problem with the label avant-garde, with its flamboyant promise of “being out front.” Rather, the issue is staying in and with the times and not letting the times drown you.

All the standard terms for inventiveness in the arts are vexing, even when well-intentioned. Experiment can suggest that the focus is on work-product or test results despite the fact that writing that is open to new possibilities is more likely to be aesthetically accomplished than work that closes off such possibilities. Avant-garde often evokes a hermetically-sealed tradition hobbled by its own triumphalism. We need avant-garde literary history to revolutionize overly narrow lineages and to acknowledge that the revolution of the word was fomented by writers who operated both inside and outside the cultural, ethnic, religious, or racial mainstreams. Which is to say, along with a host of literary scholars, artists and anthologists from the past few decades, that avant-garde history has not always acknowledged its innovators. At the same time, many of those hostile to what they call avant-garde poetry gerrymander the term to suit their foregone biases against it.

Rather than saying avant-garde, we say en garde: wake up, poetry is about to begin!

It’s not just that we need a revolution in style but also a revolution in audience, distribution, circulation, performance, perception and, indeed, motivation.

In 2015, as for 100 years before, innovative poetry continued to be controversial. Of course, there is much to be critical of in poetry’s multitude of iterations and most practitioners of anything remotely resembling the experimental are quick to make a wide range of criticism, since this is a group of unlike-minded individuals. But all the hoopla suggests that what’s innovative is, paradoxically, at the vital center of contemporary poetics and that its symbolic constructions are therefore subject to the most virulent scrutiny and worthwhile critique.

But, yes, the innovative needs to change, to revolve, or else it will become nothing more than the fashion and design wing of officially sanctioned verse culture. Or you could say all the en-garde is is an indication of change.

The exploration of identities has always been at the center of radical and exploratory poetry. Indeed, you can define a difference between official verse culture and its opposites as one between work that assumes a fixed identity and work that forges new identity constructions. In this sense, identity is a space for exploration, invention, re-creation, and experimentation. No one group has, or has ever had, a monopoly on this. The source of the most provocative American poetics is the collective linguistic expression of all groups refracted into culturally specific works.

In the brutal calculus of official verse culture, it is claimed that identity is erased in “experimental” writing. But one person’s erasure may be another’s path to freedom, just as one person’s experimental diversion may be another’s fate. We favor thick description over thin convention: the discovered over the assumed. Identity is a process and an intersection: it something that unfolds as it is veiled. We are not against writing from one’s identity; rather, we seek a more robust engagement with identity than is often found in conventional writing or narrowly defined experimental writing collections. We wanted to open up Best American Experimental Writing 2016 to a range of voices that, we hope, enrich each other by being in the same volume.

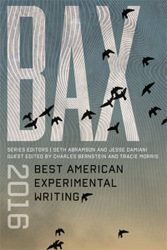

We edited the book in collaboration with the two series editors. We were asked to make 45 selections from work either published in 2015 or not yet published. We further created our own, stricter, criteria to bring more voices into this conversation: No current or recent students or colleagues at institutions where we have primarily worked. No authors who were published in the first two BAX anthologies (that meant leaving out much work that we admire). We also excluded anyone whose poetic work was published by the early 1990s. Since so many poets from this generation are continuing to do some of the best experimental work around, we felt we needed to make room here for new writers (or anyway, newer ones). But we didn’t want to leave out the older generations entirely, so we have included select works by major figures working outside genres for which they are known. We also didn’t select any translations, as we felt including just a few would fall woefully short of representing the vibrancy of poetry written around the world. We’d like to a see a book like this one just of translations, emphasizing also new approaches to the art. In addition to our 45 selections, the series editors made 15 selections. The remainder of the works in the anthology were selected from submitted manuscripts; these were picked by the series editors and us. We hope that this mix makes for a strong volume and contributes to the development of the BAX series. Although we are happy with the resulting volume, the necessary compromises among the four editors, and the inevitable space limitations, has meant that we were disappointed we could not include many outstanding works. We especially want to express our appreciation to the many extraordinary poets who submitted work we were unable to include as well as our colleagues, students and friends. We could not do what we do without our intersecting and ever-expanding communities.

Editors of anthologies committed to the best of conventional writing are likely to reject work because they have never seen anything like it before. In contrast, we tend to reject work that strikes as having been done before—unless the “done before” was done over. It’s not that great work isn’t written in forms that have been previously established: much of the greatest poetry has been written this way. But there is a still a place for something else and indeed a need for something else. That’s where we come in.

In surveying the field in 2015, we found multiple, contrasting trends including work that was multilectical, multiethnic and multilingual; site-specific; constraint-based; work engaged with visual design and layout; poetry in programmable media; work that uses web data mining; appropriation via transcription, reframing, and resisting; ecopoetics; various approaches to radical transliteration, geography, affirmation and remediation, and performance writing.

Poetry is connected to the origins of language and possibilities for language, the poetics beyond what the eye sees or ear hears.

We also wanted to include work that fell outside the usual borders of innovative poetry. We have included work of a few visual artists, including graphic artists, who work with words. And we have included transcriptions of a few writing-based songs, works whose lyrics stand up on their own as poetry. That is, we have brought together writers that aren’t usually in the same room because they come from a wide variety of social and cultural positions. Being in the same room—this collection—makes possible one, of many, necessary conversations.

Poetry is connected to the origins of language and possibilities for language, the poetics beyond what the eye sees or ear hears: what makes logic and language possible. Poïesis is soul-making and builds worlds. All the voices in this room have been given room, because the source of poetry and poetics isn’t the shadow of any one language, group, or culture. Poetry, the kind of poetry we want, is language that breaks its ties to assumed performances of understanding and assumed relationships.

In the U.S. mainstream, 2015 saw the expansion of legal civil rights for same-sex partners and more cognizance of Trans presence in American life, increasing awareness of the historic, sustained blight of police violence, particularly against Black lives. 2015 also saw declining incomes for most Americans, widespread poverty, unconscionable rates of incarceration (especially for people of color), widespread and widely noted racist and gendered aggression, the cementing of an extremist and undemocratic financial disparity between the super rich and the rest of us. And yet, there’s has also been the simultaneous atomization, intersectionality and interconnectivity of individuals, groups and, the planet.

Without a reversal of the maldistribution of wealth and power, including cultural agency, no real social progress is possible.

But great poems are still being written.

From the introduction to Best American Experimental Writing 2016. Used with permission of Wesleyan University Press. Copyright © 2016 by Charles Bernstein and Tracie Morris.

Charles Bernstein and Tracie Morris

Charles Bernstein is author of Pitch of Poetry and All the Whiskey in Heaven: Selected Poems. He is the Donald T. Regan professor of english and comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania. Tracie Morris is the author of Rhyme Scheme, Intermission, and handholding: 5 kinds. She is professor and coordinator of performance and performance studies at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York.