Our Tonya: Growing Up in Thrall to an American Antiheroine

Tracy O'Neill on the Symbolic Heft of Tonya Harding

A couple of years back, a dear friend gave me a Tonya Harding sweatshirt. The gift was not an arbitrary garment. It had been offered because my friend knew the unreasonable attachments that followed me into womanhood. The back of the sweatshirt bore the words NEVER FORGET, and I hadn’t.

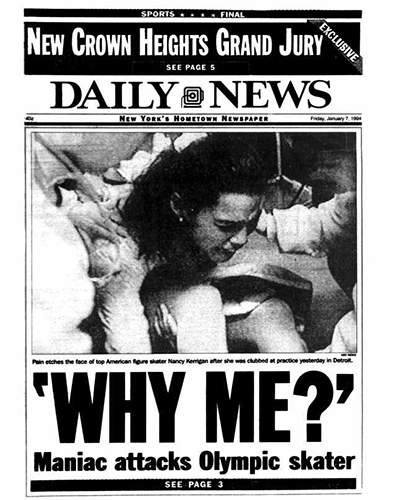

It was January 1994 when the story first broke. Nancy Kerrigan, an elite American figure skater, had been clubbed in the lower thigh after a practice session for the national championships in Detroit, the perp fleeing the scene of the crime by crashing through a Plexiglass door. Soon after, Tonya Harding won the Nationals, the notional Olympic qualifying competition, and speculations circulated that Harding had played some role in the plot against her primary rival. The space around her thickened with male idiots ill-equipped to get away with crime. Through a still new 24-hour news cycle, we were presented with two women’s faces, one in pain and the other on a podium.

I was seven at the time, and for weeks after there was only one game for a certain type of feral kid, often a girl, and it was Whack-A-Knee. Most of us wanted to be Tonya Harding, the knee-whacker. It did not matter that in fact Harding had not been the assailant, that it was, instead, a man who had lashed a billy club against Kerrigan’s leg and attempted to rent the getaway car for the crime with his girlfriend’s credit card. Nor did it matter that Harding denied any involvement in or prior knowledge of the attack on Nancy Kerrigan. In our naiveté, we believed in the truth of sides and violence, that someone always wins, and so we preferred to be Tonya. Who wouldn’t, when the alternative was squirming on the floor, mewling, “Why? Why me?”

The answer was those who wanted to be good, pitied, or pretty, none of which had ever provoked much attraction for me. It didn’t then occur to me that there were more ways to be than bad or good, vilified or pitied, an agent of destiny or a victim of fate. I hadn’t learned the term binary. I hadn’t even figured out that Detroit was in Michigan. But I’d heard from television personalities that Tonya would break athletic records, then suck down a cigarette with the kind of attitude that conveyed the thrown caution of a woman who’d never wanted to be a sweetheart. She was a young divorcée, which I took to mean intolerant of mediocrity or shit levied in her direction. She sued to go to the Olympics and skated to ZZ Top when her competitors chose the likes of My Fair Lady. Most of all, what I knew was that Tonya Harding took up the television, spreading across hours six words that women weren’t supposed to say of their rivals, or of their own ambitions: “I’m going to whip her butt.” We play-acted her with relish.

Many years later, I would be sent by a magazine to cover two Williamsburg millennials who, giddy with irony and much older than seven, had opened a janky Nancy Kerrigan-Tonya Harding 1994 Museum in their own apartment. They advertised it (or rather, they advertised themselves) with swag to the tune of pins inscribed “Team Tonya” and “Team Nancy.” The idea was that everyone identified with one or the other of the archetypal skaters. You were a broad or a darling, but you were always adversarial with another woman. At this point in my life, the reductive framing of the gesture did raise suspicion, but an ethic of feminist solidarity was not enough to prevent the unequivocal sense that my affinity was with Team Tonya. Such is the semiotic power of Harding.

“It didn’t then occur to me that there were more ways to be than bad or good, vilified or pitied, an agent of destiny or a victim of fate.”

Because before Nicki rapped, “I’ll say Bride of Chuckie is child’s play / Just killed another career; it’s a mild day,” and before Amy sang, “I cheated myself / Like I knew I would / I told you I was trouble / You know that I’m no good”; prior to Uma as The Bride autobiographizing, “I roared and I rampaged and I got bloody satisfaction”; many years after Sula but many years ahead of “sorry not sorry” being GIFed to virality; before Rihanna made Good Girl Gone Bad or “nasty women” was invented as a progressive badge of honor, there was Tonya: patron antiheroine to young women of a certain scab-kneed, too-loud, ungracious audacity. We wanted to skirt the rules in the wrong outfit. We had, at times, personalities like popped blisters. Often, we were caught in the wrong angle in photographs. We had tantrum hearts. And we wanted to be women who unapologetically did whatever it took, whatever thorny “it” our raison d’etre was.

Tonya Harding practices at Clackamas Town Center, 1994.

Tonya Harding practices at Clackamas Town Center, 1994.

As it turned out, I did not become a woman who often knew what “it” was or what it took. When I did know what I needed to do, usually that meant sitting quietly through various deprivations of id. But even after many years of measured words at university seminar tables, and the occasional shrink, and countless instances of delaying a request for something I desperately needed with the question of whether it wouldn’t be too much trouble to ask, there persists in me a blade that I once saw in Harding, and it cuts very true. I think many other women born roughly between 1980 and 1990 share the feeling. Maybe you never forget the first tragic figure whose identity you thought mapped onto your own, even, or especially, if you never really knew her.

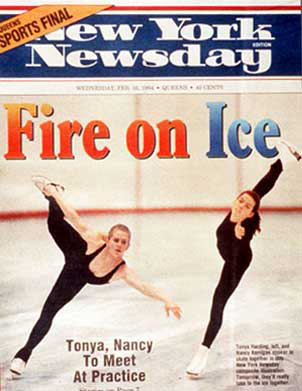

In the immediate aftermath of the Kerrigan attack, Harding was referred to in the press as, variously, a “tough babe,” “rough-edged,” “confrontational,” “defiant,” “the Darling of Dysfunction,” and with baldest malice, “white trash.” Profiles at turns admiring and smirking recounted her background as an underprivileged Portland native, how she knew her way around a truck and grew up hunting, shot pool and dropped out of high school. Though more textured portraits eventually emerged, she became, in the popular imagination, a caricature of rough and tumble American bad girlism. This image forms the basis of much of my childhood admiration, and it is what makes Harding a particularly alluring candidate for film. The fictional possibilities were clear even in 1994, and I’m not merely talking about when, in what would later be referred to at turns as “the ultimate journalistic sin,” New York Newsday published a composite photograph that appeared to show Kerrigan and Harding on the ice practicing together at the Lillehamer Olympics after the assault at Nationals. Rather, in February of that year, the New York Times published an article called “Try Casting ‘Tonya: the Movie,’” in which it reported that Tonya Harding suggested Meg Ryan could play her onscreen. Like many of Harding’s desires, the Meg Ryan casting never did actualize in the fashion she hoped.

Instead, enter I, Tonya, the new biopic directed by Craig Gillespie and starring Margot Robbie as Harding. Much of the attention the film has garnered is breathless admiration for the purportedly incredible physical “transformation” of Robbie. It is incredible, in a way. Robbie’s Harding resembles the real Harding very little at all.

*

A recent review of I, Tonya by the film critic Christy Lemire begins, “You probably haven’t thought about Tonya Harding much recently. Truly, why would you? The Olympic figure skater reached the height of her fame nearly a quarter century ago for something that didn’t even happen on the ice.” Lemire, for all her low-hanging snark, has not been paying attention. Harding was the first American woman to land the triple axel, a jump that put her on par with the top male athletes in the sport. For girls in 1991, the feat indicated that women could compete physically with men. Moreover, I, Tonya arrives roughly four years after a turn toward revisionist work on Harding, typified by a 30 for 30 documentary called The Price of Gold and a 2014 essay in The Believer by Sarah Marshall, which elaborated the notion that Tonya Harding was lambasted in classist terms by the press and never furnished a fair shake by the skating community.

It’s true that many in both the media and the skating world disdained Harding enough to make a habit of underhanded class-based criticism. George Vecsey of the New York Times even suggested Harding’s complicity in her own domestic abuse, writing, “Jeff Gillooly sounds like a masochist’s dream. His former wife, one Tonya Harding, a figure skater from Oregon, has been issuing documented cries of help over the years that he is abusive to her, but she kept going back to him, a pattern she may regret right about now.” In the two decades following the Kerrigan-Harding scandal, there have been gleeful takedowns of Harding’s post-skating boxing career, her singing, her appearance. When she was charged with assaulting a boyfriend with a hub cap, the New York Post, which can always be counted on for spectacularly malevolent puns, published a story with the headline TRASHED TONYA ON THIN ICE WITH ASSAULT in 2000.

But Marshall also claims that “[i]f Nancy Kerrigan had skated in the US Championships that night [in 1994], and had skated just as well as or even somewhat worse than Tonya Harding, she likely would have beaten her, not because of the quality of her performance but because she was more consistent, more admired, more in keeping with the sport’s ideals, and, above all, because she was the American skater who seemed the likeliest to bring home Olympic gold.” It is a counterfactual, and a strange one at that. The sport’s judges had “permitted” Harding to beat out Kerrigan and Kristi Yamaguchi, both well-respected skaters who could be said to have skated “somewhat worse,” when Harding won the same competition in 1991. And, were figure skating favored much by offtrack betting parlors, an astute gambler might note that the highest Harding or Kerrigan had ever placed at the World Championships was, in each case, second. Marshall depicts Kerrigan’s flurry of endorsement deals as preemptive— “as if the rewards for Olympic championship had already been bestowed on her”—and breaking the unofficial rules, as though the dispensation of corporate dollars has ever been meritocratic. What she fails to mention is that following the attack on Kerrigan, Nike provided Harding with $25,000 to defend her conditional spot on the Olympic team from the United States Olympic Committee.

I mention these scraps of history not to carp at Marshall but because her recuperative reading is one example of many that retrofit the Olympian to an idea at the expense of a fuller representation. For so many, Harding acts as a semiotic container for a particular worldview. Most of us have failed to see Tonya Harding the person, dazzled instead by her symbolic potential. We take her life as an allegory for whatever. We elide what doesn’t suit us. Perhaps we never wanted to join Team Tonya. We wanted her to join our team.

So it may be, as Lemire’s math indicates, nearly a quarter century past the height of Harding’s fame, but I, Tonya suggests we are not yet finished with soliciting her myth for our ends.

*

The day I saw I, Tonya, I did not wear the Harding sweatshirt to the theater, but I did cry, and I was charmed. It’s because I’m a sucker. If you are also the sort of person enamored of underdogs, who wants to believe against your better instincts in meritocracy; if your intentions towards grace have on occasion been superseded by the bubbling up of a fuck-you sensibility, and you’ve lost your composure during features like The Mighty Ducks; if you like a seedy bar and going fast, then this is probably a movie for you.

But I, Tonya’s filmmakers want to have it both ways. The screenplay takes shots at media spectacularization, and it is itself a spectacle. It emphasizes the ongoing abuse of Harding at the hands of Gillooly, her half-brother, and her mother LaVona Fay Golden, but it tends to trivialize the horror by giving Harding a slapstick kick or punch in return. It gestures toward a respect for figure skating, the activity to which Harding dedicated her early life, but treats its artistic half as a narrative key to signify the raw deal it imagines Harding to receive from judges. There is an attempt to implicate the audience’s hunger for salacious stories like Harding’s tragic downfall, but the movie benefits from exactly that appetite.

Still, though I, Tonya mostly is a romp, if reliant on condescending comedic timing. Though it commits to a mockumentary frame ill-suited to its foregrounding of domestic abuse, and though much of the characterization of secondary figures is ham-fisted dope stuff, I was taken into its thrall. The acting is frequently very good. Harding’s mother, played by Allison Janney, is withholding. She speaks with a dry, casual viciousness, and sometimes even a strained warmth that transcends the script. The pacing is propulsive, the costumes just-so. The movie hits the marks of conventional narrative with panache.

Margot Robbie in I, Tonya. Courtesy of NEON and 30West.

Margot Robbie in I, Tonya. Courtesy of NEON and 30West.

And the Harding of I, Tonya is sympathetic, a somewhat glossier version of the one drawn up by Marshall. She is scrappy and determined but a victim of circumstance, an unsupported outsider, always used and abused. This Harding is sanitized, never quite allowed to be ugly. In reality, Harding’s behavior sometimes was ugly; once, when given eight hundred dollars by her fan club to go to an Olympic training camp, she did not attend and never returned the money. She also appears to have lived with a great deal of horror: Harding alleges that she did not immediately tell the FBI of her ex-husband’s involvement in the Kerrigan attack because he gang raped her at gunpoint with two other men. But these are the sorts of complications the film does not abide.

If it does not complicate our understanding of Harding— and perhaps it is unfair to expect a fictional film to do so—where I, Tonya succeeds is in indexing certain current cultural longings. In the movie, the mildly crass Harding complains that the judging of figure skating is “rigged” to favor those who assume the visual coding and mores of elites, recommending that they suck her dick. The media is represented by Bobby Cannavale, a slick and cynical Hard Copy producer, more interested in whipping up a lascivious story than the Fourth Estate. Arriving at a moment of handwringing over the gap between coastal elites and the white working class; over the complicated relationship between social media, legacy journalism, and fake news; over racialized violence and calls for free speech; Robbie’s Harding is a populist without the nuclear codes, done wrong by a flagrantly tabloidized press. She is brash only because she is an unvarnished American who means what she says. She is, essentially, a big-haired innocent in a prim world of blue-blooded power. The film invites us to view her as a hardscrabble hero our country has misconstrued.

Stephen Rogers, I, Tonya’s screenwriter, is a man who has built a career on redemption narratives. His best known work is Hope Floats, in which Sandra Bullock gives a man her daughter disapproves of a second chance. “America,” his Harding muses. “They want someone to love, but they want someone to hate.” With this utterance, the figurative camera scope turns. We are meant to be a better, less polarized America.

*

The scene in I, Tonya that made me cry occurs toward the end of the film. In it, Robbie’s Harding receives the judge’s ruling after pleading guilty to conspiring to hinder prosecution of the Kerrigan assailants. The terms include that she will be banned from figure skating competition for life. Robbie begs like a child to be sentenced to jail rather than lose skating, and while her pleading is not quite convincing, the moment captures something of that myth of a woman who would do whatever it took, even as it is clear that whatever it takes—jail, supplication—is insufficient to prevent the foreclosure of her dreams.

I watched this scene and knew it was not factual, knew that the living, breathing Harding had released a statement shortly after the sentencing through her attorneys: “I am committed to seeking professional help and turning my full attention to getting my personal life in order. This objective is more important than my figure skating.” But it didn’t matter much in the moment, nor did a sense that the filmmakers mostly understood Harding quite differently than I did. My face was wet in the movie theater, and I heard another woman stifling little sobbing gasps behind me.

In the days since, I’ve thought of that other woman in the dark several times. I’ve wondered what Harding meant to her. I’ve wondered if she was someone who insisted all other visions of Harding were not quite right, who, though disabused of its truth, held onto the bright one of her own from childhood. I wondered if I’d find that she, too, felt what I did. The way I remember it, our faces looked into a great square of light, our disbelief was suspended, and we wanted the world to be better for the woman we once imagined we were or could become, the one who we reached to claim as our own, who has always been too much to be contained.

Tracy O'Neill

Tracy O’Neill is the author of the novels The Hopeful and Quotients. In 2015, she was named a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree, long-listed for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, and was a Narrative Under 30 finalist. In 2012, she was named a Center for Fiction’s Emerging Writers Fellow. O’Neill teaches at Vassar College, and her writing has appeared in Granta, the New York Times, Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Bookforum, and other publications. She holds an MFA from the City College of New York and an MA, an MPhil, and a PhD from Columbia University.