I wish I could say it was coincidence that, in 1991, I published a novel called The Hours, which arose out of an imagined day in the life of Virginia Woolf in the early 1920s, when she realized she was writing a novel to be titled Mrs. Dalloway and not, as had been her original intention, a novel called “The Hours.”

My use of Woolf ’s original title was thievery, pure and simple, albeit thievery with honorable intentions. The fact that it was legal thievery (titles cannot be copyrighted, even if they’re not yet in the public domain) only slightly mitigates it.

I will say that I meant it as an homage. It seemed right that my own novel, which would not have existed without Woolf ’s, should scavenge a title she had tossed onto the scrap heap.

My novel, with its appropriated title, was about the greatness of Mrs. Dalloway but was also, more immediately, about the mystery of the book’s creation. It’s one of the fundamental questions about a significant work of literature: how did the writer get from having nothing beyond a few images and inclinations to a novel like Mrs. Dalloway? At what point, and by what means, did that inner turbulence of the mind and heart coalesce into a sentence, and then another, and another, and ultimately into a complete, transcendent, narrative?

I hope no one will be disappointed to hear that, in my own novel, I don’t solve that particular mystery. But, as far as I can tell, novelists rarely if ever solve mysteries; novelists can only hope to illuminate and deepen essential human enigmas and to chart the points at which relatively simple questions blossom out into profound ones.

Writers often change the titles of their books, often more than once, as they write them, and sometimes the reconsidering of a title reflects a deeper shift in the evolving nature of the book itself. Woolf’s new title for her novel-in-progress implied that she’d decided, relatively early on, that she was not going to write, not exactly, the book she’d initially set out to write. Had Woolf completed a novel called “The Hours,” it would not have been the Mrs. Dalloway that has become a cornerstone of 20th-century literature. One can’t know, of course, if Woolf’s “The Hours” would have been a lesser novel than her Mrs. Dalloway, but it would have been a different novel.

Had Woolf completed a novel called “The Hours,” it would not have been the Mrs. Dalloway that has become a cornerstone of 20th-century literature.Mrs. Dalloway was Woolf’s fifth book. Her first two—The Voyage Out and Night and Day—are better than most works of fiction, but they are relatively traditional; they’re not the work of the radical, revolutionary writer we’ve come to know. It was only after Virginia and her husband Leonard moved from Central London to the suburb of Richmond and set up their own print shop, which they called The Hogarth Press, that she began to write the books she chose to write, as she chose to write them, without considering the demands of an editor or a publishing house.

As she declared in her diary, “I am the only woman in England free to write what I want to write.”

Among the Hogarth Press’s initial publications were Woolf’s short story collection, Monday or Tuesday, and her third novel, Jacob’s Room. Jacob’s Room was an enormous step for her as a novelist: essentially a character sketch without the central character; a portrait of a man drawn largely from the accounts of others who knew him.

It was an extremely good, inventive book. But her next, Mrs. Dalloway (briefly known as “The Hours”) would be her first indisputably great book.

What Woolf wanted to write, when she embarked on her fifth novel, was a narrative about London after World War I, the War to End All Wars, which not only killed at least 17 million people but introduced to the world such catastrophic innovations as the armored tank, the flamethrower, and mustard gas. Many of the soldiers who survived the war returned disfigured, their faces and their minds rendered almost literally unrecognizable. The streets were haunted by people who were, on one hand, deeply damaged specters of the conflagration but were, on the other, brothers and sons and husbands, come home to resume their lives.

Woolf was determined to write a novel set in an England complicatedly both altered and restored; an England that was merely shaking off the vestiges of a long, bad dream superimposed over an England that would never recover from its losses.

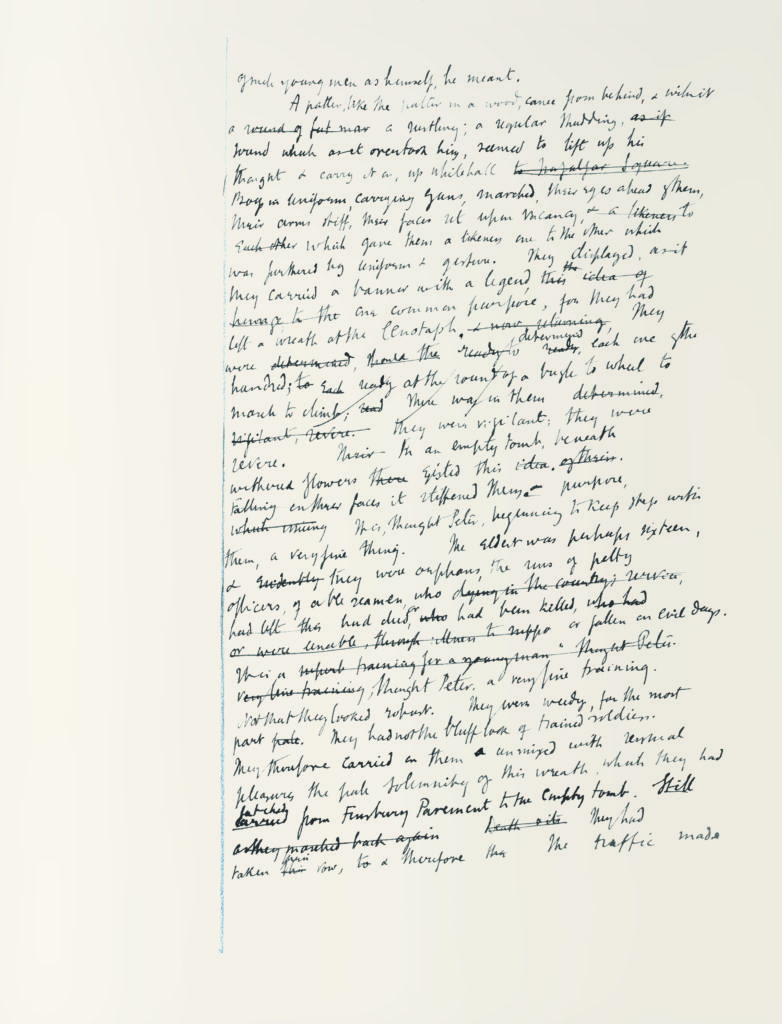

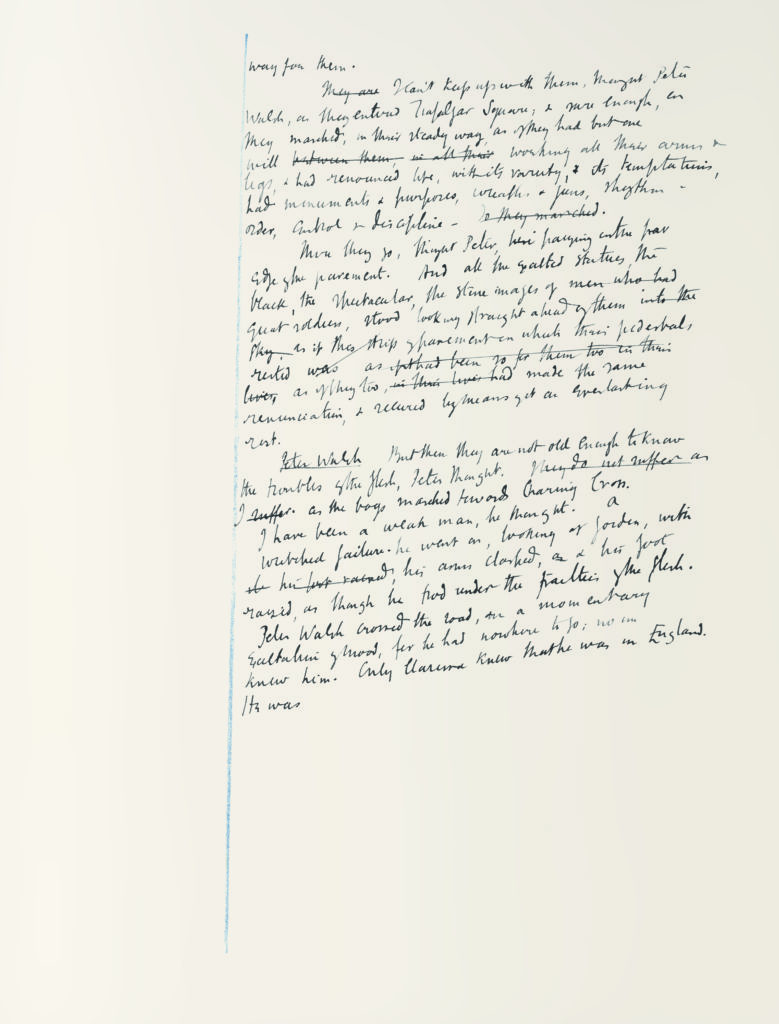

Her initial foray opened with the unbroken London of statues and steeples and bells; with a middle-aged man named Peter Walsh walking among them; and with a troop of soldiers marching past to lay a memorial wreath to the war dead at the Cenotaph in Whitehall. Peter Walsh, musing on his own failures and frailties, thought of a woman named Clarissa . . .

And, in a sense, handed the story over to her. Peter Walsh would continue to play an important role, but the book would belong to Clarissa Dalloway. Its title would be Mrs. Dalloway (we note Woolf ’s choice to use Clarissa’s married name).

Clarissa Dalloway had stood at the periphery of Woolf’s attention since she started writing fiction. Mrs. Dalloway appears in Woolf ’s first novel, The Voyage Out, and in several short stories, most prominently “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street,” written prior to the novel that bears her name.

Clarissa Dalloway was the quintessence of upper-class English rectitude, if in “upper-class English rectitude” we include the ability to command a considerable household staff; to throw large, lavish parties that seem to have been effortless; to not only charm every guest but to remember every guest’s name.

If those capacities didn’t rank very highly on the scale of international relations, neither were they beside the point. Richard Dalloway, Clarissa’s husband, a member of Parliament, relied on Clarissa to provide, to his cohort and his superiors, the warmth and magnetism he himself lacked.

She was more than an ornament. She was a vital element of her husband’s career.

Clarissa was also sensitive to beauty, to life itself, in ways her husband and his peers were not. Clarissa may have been capable of pleasant social deceits but she was, more importantly, a truly generous spirit. If her personality was o en put to specific use, her personality was neither calculated nor cynical. She was a genuinely captivating person. And, as it happened, her natural magnetism rendered her a particularly strong candidate for the position she occupied—society hostess— at a time when there weren’t many other positions, of any kind, open to women.

Woolf did not dislike Clarissa for being more immediately concerned with buying flowers for the house than she was with treaties or civilian casualties, nor did she underestimate the value of her efforts. As Woolf herself put it, “This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room.”

Woolf ’s fifth novel, then, evolved into a diptych of sorts: the simultaneous story of Clarissa Dalloway and a shell-shocked war veteran named Septimus Warren Smith. As Woolf notes, “Sanity & insanity, side by side, Mrs. D. seeing the truth, [Septimus] seeing the insane truth.”

And so, a book about two parallel lives that reflect the dividedness of England after the Great War: one England returned to sanity, another driven permanently insane.

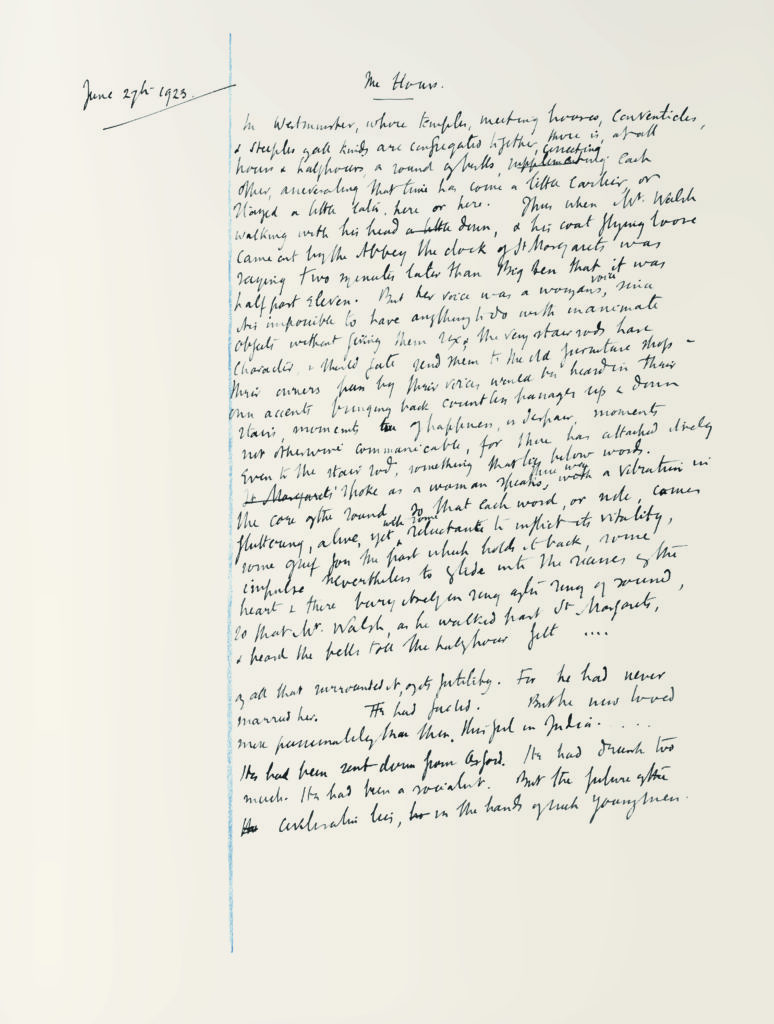

And so, an opening passage first written as…

In Westminster, where temples, meeting houses, conventicles, & steeples of all kinds are congregated together, there is at all hours & halfhours, a round of bells, correcting each other, asseverating that time has come a little earlier, or stayed a little later, here or here.

…became:

Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer’s men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning—fresh as if issued to children on a beach.

As Woolf would say, of Mrs. Dalloway, “I meant to write about death, but life came breaking in as usual.”

If one were to try to summon Woolf as an artist, in the shortest possible sentence, that sentiment of hers would probably do. We see it played out, albeit in miniature, in the opening of a book called “The Hours,” about bells and memorial wreaths, rewritten as a book called Mrs. Dalloway, about the inextinguishable beauty of life itself.

Death, in the form of Septimus Warren Smith, will appear in the book. But the book itself opens, and closes, with life, continuing.

Life comes breaking in, as usual.

–April 7, 2019

*

Below are sample pages from Virginia Woolf’s original manuscript of “The Hours.” Click each image to enlarge.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Hours: Virginia Woolf’s original manuscript of Mrs. Dalloway. Used with permission of SP Books. Introduction copyright © 2019 by Michael Cunningham.