Loving—And Leaving—Turkey in the Midst of Upheaval

Andrew Wessels on an Accidental Return Home

I’m running my hands along these shelves of books; I’m leaning over my desk to run my hands along these shelves of books. These books that had been boxed away and held in storage, unseen, unread, untouched for nearly two years. My books that were carefully wrapped in plastic, tucked into cardboard boxes, and stacked in a ten foot by ten foot storage room near the airport and left behind. My books that now are with me, again.

Eighteen months ago, my partner Zeliha and I left our home in Los Angeles and moved to Istanbul. I found a job teaching at Koç University, a small liberal arts-style college whose campus is perched on top of a hill overlooking the Black Sea. We found an apartment with a balcony and a view of the Bosporus. I started a new collection of books, I found a publisher for my first manuscript, I wrote a new manuscript, and I explored my new city.

Eighteen months later, and we’ve moved back to the US on the eve of my first book’s publication, in the middle of a transition to a frightening new President, and on the heels of a failed military coup and a series of escalating terrorist attacks. In 18 months, we built a home that fulfilled us. In 18 months, we built a life.

Now, I am in my old city surrounded once again by my books, wondering how to rebuild a life again.

This is a story I have to tell, and a story I don’t know how to.

*

In the first days of 2017, in the immediate aftermath of the New Year’s Eve shooting at the Reina nightclub on the shores of the Bosporus, I watched my American friends populate my Facebook news feed with articles listing the series of attacks in Turkey in 2016. The lists included bombings by ISIS and PKK, a coup attempt, and now a mass shooting. The idea, I think, was that this list could describe what living in Turkey was like, that it described my experience of my home. My friends read these lists and were filled with fear and trepidation. Istanbul and Turkey must be a police state, a war zone, a bottomless well of darkness and fear.

I stared at these lists as we prepared to move back to the US. Zeliha and I had already sold off our furniture, vacated our apartment, and completed our final days at work. We were to leave Istanbul in four days.

What exactly does a list like that mean or do? At their most basic, lists list things. Like data, lists present themselves as neutral. But also like data, they are not neutral at all: Who chooses what list to make and publish? Who chooses what information is included in and excluded from the stated list?

These lists about Turkey seemed to say: this place has become terrorized.

But why list this? Why not write and publish some other list?

Here is a list of 5 horrifying tragedies in the United States in 2016:

1. February 20, 2016. Kalamazoo, MI. Jason Brian Dalton, an Uber driver, kills six and wounds two while picking up fares. Dalton is apprehended alive.

2. June 12, 2016. Orlando, FL. Omar Mateen kills 49 and wounds 53 in Pulse Nightclub. Mateen is the 50th death.

3. August 13, 2016. New York, NY. Oscar Morel shoots and kills two execution-style in the early afternoon in Ozone Park. Morel is apprehended alive the following day.

4. September 26, 2016. Houston, TX. Nathan Desai, dressed in Nazi regalia, opens fire at a shopping center in the West University neighborhood killing none and injuring nine. Desai is the only death.

5. December 5, 2016. Albuquerque, NM. George Daniel Wechsler breaks into the home of his ex-girlfriend, shooting her and her children, killing all four. Wechsler is the fifth death, of a self-inflicted gunshot.

What meaning do we derive from this list? What does this tell us about life in each of these cities, about life in the United States? How does the information provided and left out of each entry change the list?

For most residents of the US, this list is easily contextualized: We have 365 days in a year, in a expansive country of hundreds of millions of people, with lax gun regulations, with societal issues rooted in isolation, racism, mental health, and poverty. Each of these tragedies can be given its own complex and convoluted backstory. Those events are things that happened, horrifying events. But, we can immediately say, there is so much more here that isn’t this.

And that is a list of five arbitrarily chosen tragedies (why these five and not five completely different tragedies?). A complete list of mass shootings in the US is meaningful in another way, through its epic length. What does that list say? Does it say something different about life in America? In what ways are these lists accurate, or inaccurate, of a lived experience here?

The Turkish list had the effect of reducing the experience of living in Turkey in 2016 into a consumable morsel. The only rational response to such a list is to assume that the country is a war-zone, the military apparent everywhere, a populace descending into abject fear, empty streets, the constant sound of bombs and gunfire heard from a bedroom window.

Looking at that list, I ask myself: Was that my home?

*

I have two opposite ways of describing my experience in Istanbul. When confronted with a question about the assumed horrors I witnessed, I understand my experience in opposition to that extreme. Each morning, Zeliha and I woke up and went to work, enjoyed our neighborhood, and went out for dinner and drinks on weekends. On Fridays, I met with the poet Nurduran Duman to work on translations of her poetry and wander through the many neighborhoods of this city. Fear never entered my day-to-day consciousness. I was happy and I felt at home in a way I hadn’t experienced before as an adult.

But when confronted with a question that normalizes the situation in Turkey, my experience is understood against that. I think of the ever-widening net of arrests of academics and writers in the wake of the failed coup attempt. The country-wide block of Dropbox, Google Drive, and GitHub to quell a government leak, and the semi-regular shutdowns of social media platforms for a litany of reasons both significant and insignificant. The militarized vehicles that sit in front of the local police stations. The plummeting value of the Turkish Lira. The empty tourist areas. The constitutional referendum that just passed and will lead to the official crowning of a President for life with near-absolute powers. The bombing at the stadium in Beşiktaş half a mile from where Zeliha and I were eating dinner 15 minutes earlier, a bomb that killed a student from my university and nearly killed a student in my class whose taxi had just passed that exact spot a few minutes before.

When I think of these two opposing experiences simultaneously, I notice that one—the optimist—is rooted in the present. And the other—the pessimist—is rooted primarily in the future and the past. My life was a joy. The things that surrounded me beyond my control—the geopolitical forces—were a fear.

*

About a month after moving back to LA and three weeks after moving into my new apartment, I flew to Washington, D.C. to attend the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference. I’ve attended this conference every year since 2010, but this year my reason for attending was new. Previously, I always worked for an organization: Black Mountain Institute and UNLV, the literary journal The Offending Adam, or for Les Figues Press.

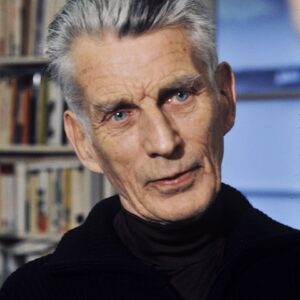

This year, I went to support the publication of my first book, A Turkish Dictionary. The book chronicles my early experiences with Istanbul, my initial immersions into the Turkish language and history, and with the architecture and faith of Islam. It is, in part at least, a love letter to the city that I wanted to call my home.

When I arrived in D.C. late Thursday night, I still hadn’t seen the printed book. A box of advance copies had been shipped in directly from the printer. On Friday morning, I was to receive the box, open it up, and hold my book for the first time, moments before entering the conference hall to ostensibly help launch the book.

I spent eight years writing, rewriting, and submitting the manuscript before it was accepted for publication. Over these years, as I imagined that potential moment of holding the book, I assumed that I would feel a sense of accomplishment, of joy, of contentment, a moment of resolution marking the accomplishment of a goal I’d worked toward for my entire adult life. But when I opened the box and held the book in my hands for the first time, my immediate and only thought was one of relief that the printer hadn’t messed up, that I didn’t notice a significant typographic mistake, that I didn’t want to re-tape the box, send it back to the printer, and pretend that it never happened. Emotionally, I felt nothing..

My only feeling was the realization: I don’t live in Istanbul anymore. Istanbul is no longer my home. For the first time it was real that I was no longer going back.

*

On the day of the attempted coup in Turkey, I was on the other side of the world in Austin visiting my family. I had arrived barely 12 hours earlier in what turned out to be one of the last international flights before the airport was shut down. At the time of the coup’s start, I was texting with Zeliha, who was about to go to sleep in our home in the Tarabya neighborhood in northern Istanbul. I sent her a selfie, and we traded a few joking texts. Then, as I was about to put down the phone, she texted again: I think we’re having a coup.

The next minutes, hours, and days were frightening, for a variety of reasons and in a variety of ways. First, there was fear for Zeliha’s safety and the safety of my family and friends living there. Parliament bombed by fighter jets. The President giving a news interview from his airplane using FaceTime on his iPhone. The bridges over the Bosporus blocked by tanks. Soldiers everywhere and then waves of citizens in the streets attacking those soldiers. I watched the explosions, the shootings, the deaths, the confusion and tumult from thousands of miles away on my iPhone on Facebook Live and Twitter.

As the coup waxed and, ultimately, waned, the fear took on a new position: Would I be able to return? In the days immediately following the coup, a series of crackdowns and mass firings, arrests, and emergency measures potentially impacted my standing in the country. The government first fired large swaths of academics and educators allegedly or potentially connected with the coup. Many were also arrested. A blanket travel ban was placed on all academics that required university instructors return to their homes from vacation and report to their offices with future travel abroad restricted. For a week while I sat in Texas, it was unclear whether this ban included foreign academics, and thus whether I would be entrapping myself by returning home.

The firings escalated. A statement drew limits or implied a calming. A new operation resulted in hundreds arrested. Businesses re-opened, public transportation re-opened, while universities and schools were shut down across the country, never to re-open. The ruling party implied that America and the CIA might be partially responsible for the coup attempt. The arrested teachers’ offices, desks still filled with partially-graded papers and unfinished research, were left untouched as entering a now-tainted person’s office could be grounds for one’s own connection to the coup, and eventual firing and arrest. Throughout, it was hard to know what was right, what was wrong, what would happen the next day, the next month, the next year.

I didn’t know whether I would fly home or not until the morning I was scheduled to depart. While still with no knowledge of the country’s medium or long-term stability, I had learned one thing: I would be allowed to leave again if I returned to the airport. So I flew back to be with Zeliha, to be with my in-laws, to be with my friends, to be with my students, and to be home.

*

As the summer turned to fall and the new semester started, we began confronting the question of what we would do in the aftermath of the coup attempt, the crackdown on academia, the economic decline, and the political instability. Our choice wasn’t only should we leave Istanbul? but also should we return to the US? More specifically, did we feel safe moving to a country where the incoming President was stoking anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim xenophobia? Did we feel safe moving to a country whose legislature and President have a central platform of denying and eroding women’s rights?

Zeliha is a naturalized immigrant who became a US citizen a few years ago after years of applications, interviews, and what could only be described as extreme vetting. Zeliha and I are also both Muslim Americans.

We felt stuck between, unable to discern where appropriate caution ended and emotional overreaction began. We ultimately decided to move, to at least shift from a deteriorated situation to a deteriorating situation. The final two straws were the arrest of some of Zeliha’s former professors from Istanbul University and the realization that certain sections from my forthcoming book could make me a target for deportation or arrest if seen by the wrong person in power.

We felt that going offered a place where we could still fight for the life we wanted to live. We are still unsure whether this was the correct or best or happiest decision.

*

Our flight landed in LA on January 5, shortly before the inauguration. Today, I wonder what would have happened had we arrived after the inauguration or, more worryingly, after the first travel ban. As Muslims, would we be singled out for additional scrutiny? Would Zeliha, a Turkish-American dual citizen, be pulled away into a back room with no council and no due process?

The ban entrapped a friend of ours from Turkey, not a country on the executive order’s list. He was held for four hours. During this governmental transition, the number of hate crimes across the country has increased, including mosques being desecrated and destroyed by fire. Indians and Sikhs, likely mistaken for being Muslim, have been attacked, shot, and killed. A state legislator in Oklahoma required that his Muslim constituents complete a bigoted survey before being allowed to voice their concerns. Even after completing the survey, the constituents were still not allowed to voice their concerns. A second travel ban was ordered and struck down.

Our return, then, came with a sense of urgency: to fight for our ability to live with safety and freedom. A couple of weeks after arriving, we were on the streets protesting at the Women’s March LA and the anti-travel ban protests at LAX airport. The massive crowds at both protests buoyed our spirits. But each moral victory comes with an attack from another angle. The first travel ban dies but a new one is quickly put in its place. One mosque arsonist is arrested but another burns down a convenience store. Mike Flynn resigns but Representative Steve King tweets out in support of Geert Wilders, writing a message advocating for eugenics and Muslim genocide.

Can we call this place a home, my home, our home?

*

One of the themes I explore in A Turkish Dictionary is the conflict between name and erasure. For example, a student learning about the Fourth Crusade might make a flashcard of the name Enrico Dandolo, the Doge of Venice who led the sacking of Constantinople. It might include the fact that Dandolo died in Constantinople shortly after his victory and was, according to lore, buried in the Hagia Sophia. Dandolo’s name is etched into a nameplate that marks this resting place in the floor of the upper level of the Hagia Sophia. But there are no bones beneath this nameplate. The tomb is empty.

This apparent tombstone is the most visible remnant of the Fourth Crusade in the city. While there are various ruins that point to Constantinople’s past still standing, this is the one monument that points directly to the Crusade where one group of Christians took the city from a different group of Christians, killing countless soldiers and citizens in the process.

Dandolo’s name, then, becomes a metonym for the Fourth Crusade, and the tombstone becomes his triumphant entrance into the city. Those countless dead bodies, whose names were never written, were dumped into the Golden Horn and Bosporus to float away into oblivion.

The founding of the United States can be conveyed by saying “George Washington.” The founding of the Turkish Republic can be conveyed by saying “Ataturk.” The founding of Istanbul can be conveyed by saying “Fatih the Conqueror.” The founding of Constantinople can be conveyed by saying “Constantine the Great.” “Peter” invokes the Catholic Church and “Muhammed” invokes Islam. The essence of God is contained within the name of God.

What we remember is what is written down. Or, more specifically, what is written and not ultimately erased. The name that has been written a thousand times in a thousand places, etched over and over, will have this power of survival.

This is the power that the two Presidents of the US and Turkey understand and crave so much. Their names must be seen everywhere to ensure that they will always be seen somewhere, so that both will survive even after death. And it is underneath the weight of these names, the policies that these names can enact, that I must try to figure out a way to build a home.

In my new home, surrounded again by my books, I run my hands along them and consider the names on the covers: these authors, this group of people I wanted to join, to write something and to have my own name printed, to have my own book on other people’s bookshelves, to have them hold my pages and read my words and participate in this strange and isolated conversation between writer and reader. I see my own name now printed, stamped onto the cover and spine of this book and all its copies.

To some degree, a sense of self was what I hoped to find in writing my book. And what I found, at its end, was that I watched it disappear. Who am I and who should I mean to be?

*

Here are some things that I wanted: I wanted to live in Istanbul. I wanted to teach the students at Koç University. I wanted to sit on the balcony of my apartment and watch the ships move up and down the Bosporus. I wanted to see the Black Sea appear as my bus to work approached the campus gates. I wanted to watch the figs in the garden bud, grow, ripen, and be devoured by the birds. I wanted to see Zeliha spend more time with her family. I wanted to work with Nurduran for an afternoon of translations followed by a beer. I wanted to spend weekend nights out late with friends sharing a meyhane table, a glass of raki, and the sea air. I wanted to strengthen the home we were building together.

I didn’t mean to return to LA, at least not now. I meant to stay in Istanbul, I meant to teach my students there, and I meant to write more books and read more books, I meant to walk along the old city walls, and I meant to visit countless mosques and neighborhoods and tea gardens and meyhanes. As I write this, I meant to be preparing for my seventh week of classes. I meant to be preparing my courses on Yasumasa Morimura, Frida Kahlo, originality, and the presentation of the self. I meant to be reading my students’ first essays and preparing for paper conferences with them.

Of course, I’m doing none of these now. I’m approximately 6,855 miles from what is supposed to be my home. We couldn’t stay, and we couldn’t go, but we left, and now I’m here: a place that has become my home again for a third time, accidentally.

Andrew Wessels

Andrew Wessels currently splits his time between Istanbul and Los Angeles. He has held fellowships from Poets & Writers and the Black Mountain Institute. Semi Circle, a chapbook of his translations of the Turkish poet Nurduran Duman, was published by Goodmorning Menagerie in 2016. His first book, published by 1913 Press, is A Turkish Dictionary.