Illuminating Forgotten History with the Bright Light of Fiction

Dave Boling Follows a Thread of Family History to Tell Untold Stories

It’s a typical conversation-starter for authors: “What are you writing about these days?”

My answering, “the Anglo-Boer War,” triggered a typical response. The interrogators would tilt their head and nod, buying time to find a way to say they had no idea what I was talking about.

I loved it. Their cluelessness meant the topic I’d chosen was crying out to be a fictional backdrop. Since veering from journalism into fiction, I’ve taken to rummaging around in history’s dusty attic in search of stories that haven’t been told, or have gone untold for so long their messages warrant revival.

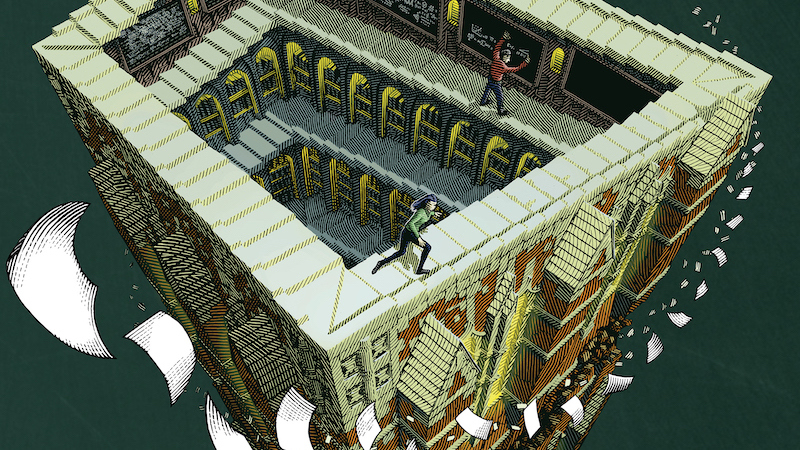

The enormity of world history leaves some events resigned to little more than a few arid paragraphs of raw statistics. That’s how “forgotten” wars get that way. It leaves the author to transport the reader back in time and into the minds and hearts of those who lived through it, or very possibly did not live through it.

Over the years, I’ve taken tentative speed-dates with dozens of historical topics. My conclusion is that a good story stands on its own, but the winners are enhanced by a degree of contemporary relevance. Is there something to be learned from this piece of history? Can it explain how we got here, or how we might find our way out from where we are now?

For instance, I came to know a number of Basques who told emotional stories of the bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, I always expected somebody to re-examine Guernica as a forerunner atrocity. But when I mentioned Guernica to friends, most thought of the Picasso mural rather than the event that spawned the artists’ creation. So I co-opted the bombing as the structure supporting my novel Guernica.

Later, when looking back at the life of my British grandfather, I learned that he had been a young soldier during the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa at the turn of the 20th century. A startling fact leaped out at me: The British were the first to establish extensive concentration camps, interning displaced Boer families that had been burned out of their farms.

In the poorly administered and under-supplied camps, disease and malnutrition killed some 27,000 women and children—far more than the combined fatalities of soldiers on both sides. I was outraged by my ignorance of this barbarity, and it led me to write my novel The Lost History of Stars.

The underlying connections to contemporary politics seemed obvious. The Brits’ botched imperialism and nation-building in the Boer Republics was triggered by the discovery of gold and diamonds there. A century later, oil was the resource that led to what I considered misguided incursions into the Middle East, and the subsequent regional instability. Clearly, this joined the surfeit of examples where history was ignored and then repeated to sad effect.

And how similar must be the hardships of the Boer children in British concentration camps to those of the refugees from the Middle East, those whose stories are still emerging?

Authors diving into little-known events bear the responsibility of providing cultural and historical context—preferably without gumming up the narrative. It’s a delicate balance, and it’s best to let the history reveal itself through its impact on the characters. Historically accurate scene is crucial, but labor-intensive research is required.

My Guernica research was still close enough in time to the event to allow for the interviewing of survivors. Their priceless descriptions helped me to hear and feel and see that specific moment in time. The Boer War book offered a different challenge, having no personal eye-witnesses to interview. Diaries and letters from that time supplied detailed insights, in fact, they were fresher, coming from contemporaneous notes rather than being filtered through memory.

The best first-person accounts were provided in the book The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell, by British social activist Emily Hobhouse, who visited the camps and revealed their squalor to the press back home.

Several published diaries were particularly invaluable. A.D. Luckhoff, for instance, published a diary of his time as chaplain of the concentration camp in Bethulie. He wrote of his hurried services over the graves of 300 victims in a span of 25 days—most of them children. His spare notes captured his sense of helplessness, and his amazement that the rest of the world could ignore the atrocity.

Museums are wellsprings of scene. The Anglo-Boer War Museum in Bloemfontein, South Africa, for instance, supplied pictures of the camps and prisoners, and exhibits of weapons and clothing and the stuff of daily existence. I took pictures of everything so I could study them at home when I set about describing the various settings.

Still, making characters real and human while being true to the historical influences more than a century earlier is a challenge—particularly for a sixty-something male author relying on a narrator who is a female in her early teens. I interviewed several women psychologists who helped me with the complexities of the female psyche at that transitional age, particularly in the face of dire emotional and physical challenges.

Additionally, three books provided personal accounts that informed my protagonist. Anne Frank’s diary, of course, inspiringly revealed how such innocence and innate goodness can sustain a young person. The works of Viktor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning) and Elly Hillesum (An Interrupted Life) provided personal insight from their Nazi concentration camp experiences.

Another challenge specific to this topic existed from the start, and almost caused me to drop the project. How difficult was it going to be to create a sympathetic protagonist while knowing that many contemporary readers connect the Boers to their descendants who became the Afrikaner minority that instituted the repressive apartheid system in South Africa?

The Boers also had fought many battles against the indigenous peoples in the process of establishing their two small republics before the Boer War. Hadn’t they oppressed the natives before the British oppressed them? Maybe the nature of their history in South Africa is why the stories from these camps have gone so largely unexamined.

Even if it felt politically touchy, I had to keep my narrator true to her perspective. She was a young girl who knew little of the world other than her family farm, with beliefs instilled by her grandfather and parents, and shaped by their rigid adherence to an Old Testament view of the world.

I decided to use those beliefs in the early stages of her personal arc. By the time she returned home, matured by her camp experience, she had started to question so many of the things she believed as true, many including her family’s behavior and their core values. Aside from the many hardships the war brought to her country, it certainly gave her a broader world view.

Perhaps this becomes a bigger question for historical-fiction writers: Should we only tell the stories of the indisputably redeemable? Those who come out on the “right side” of history? I think that’s too narrow an approach.

And the drama in this slice of time seemed so compelling, showing how the cycle of war and inhumanity spins. The oppressors sometimes become the oppressed, and while the battlefields and methods change, the victimization continues.

I wanted this fictionalization to evince what I considered two great fallacies of war: One is the common notion that soldiers monopolize the pain and death. Paying such little attention to the innocents who die in every war is history’s inexcusable oversight—one I feel that fiction writers are obliged to correct. The other is the misguided concept that anybody ever learns anything from a war other than new ways to conduct the next war.

All those things, the geopolitical power plays, the hunger for resources, the movement of armies like lethal chess pieces, are covered by history books. And even then, all too briefly. It’s left to the novelists to celebrate the small, hard-won individual victories, and the unseen insurgencies of the brave characters brought back from forgotten wars via historical fiction.