How to Write a Poem About a Cemetery: Speaking with Jennifer Firestone

MC Hyland interviews the author of Gates & Fields

Jennifer Firestone is a poet whose next move is always a thrilling surprise. Her work spans topics and approaches: from a critique of tourism embedded in a first-person travel narrative (Holiday, Shearsman 2008), to a book of invented speech in the voices of her children’s stuffed animals (Fanimaly, Dusie 2013), to an extended meditation on lap-swimming (Swimming Pool, DoubleCross Press, 2016). Her newest book, Gates & Fields, recently out from Belladonna*, takes on funeral practices and mourning with an exquisite sensitivity to language, ritual, and place. This past spring, over the course of a couple of months leading up to its release, Firestone and I discussed Gates & Fields over email.

MC Hyland: One of the first things that struck me about Gates & Fields was its sense of spareness and restraint. I think, considering your writing output as a whole, this spareness is maybe less striking, but compared to the book of yours that I’ve spent the most time with, Swimming Pool, it’s really a whole different linguistic world! These two books, placed side by side, made me think about the relationship between embodiment and language. What experiences bring us toward language (or language toward us) and what experiences move us further away from language? This book made me think about grief, or mourning, as not only a feeling of physical dullness, but also a kind of relation to words, in which they may empty of meaning, or come into question, or echo.

All of which makes me wonder: how did these poems feel in your body as you wrote them? Where, physically, did they come from? Where and how do you feel them when you read them?

Jennifer Firestone: From the beginning (more than perhaps in my other books) Gates & Fields was to me a question about language, about which words might appear in the face of grief and death. I didn’t want to write this book to express universal ideas about death—as if there were such a thing—and yet I know there are words and images that are conventionally associated with this topic. And so how this book happened was in my resistance to the idea of its conception. I’m always struck by what happens to language when one feels like it is stepping into something un-enterable, even incommunicable. The “spareness and restraint” you reference most likely reflects some of that struggle to write into this space, the need for the words to be suspended.

I also privileged sound. I heard it as meditations, not a large looping one but several. I heard ghosts and a woman appeared.

This book is very different from my last book, Swimming Pool. Swimming Pool was a conceptual project where I wrote a series of proseish poems based on swims at a public pool over the course of a six-week period. Though a lot of the work in Swimming Pool was also about the unknown and unknowingness, I ultimately felt more permission there. The work was physically embodied through the act of swimming and there was the semblance of community that suffused the work. The movement of swimming, the ideas in one’s head while swimming were ultimately generative and about accretion.

Gates & Fields, though also placed among a kind of community, occurs not so much in real time. It exists in various alternate spaces and there’s less certainty. Thinking of Emily Dickinson’s work, with which Gates & Fields is in dialogue, it makes sense that she mostly had these tight, small poems. Perhaps one can think of all her poems as one large poem, but as discrete poems they carry just enough to balance the weight of what they take on. There’s a level of care and selective thinking through ideas of spirit and philosophy that can only go on for so many words.

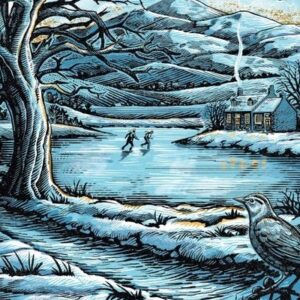

MCH: Your mention of Dickinson made me go back and re-read “Because I could not stop for death,” because of course her “carriage” is one of the vehicles (in many senses) of your book—and it made me realize that fields—”the Fields of Gazing Grain”—are, of course, one of the “sights” Death’s carriage passes by. It feels like one of the ways that your thinking and Dickinson’s diverge is in the sense of place: although your “fields” are minimally described, they seem like places in the way that places in Dickinson’s poems rarely do. Here’s a passage in Gates & Fields that I like, in part because its small descriptive details allow me to build a sense of a specific person in a specific place: “She bringing her hands through the field / The thistle sweeping her by / The wind or moan of field / The sheep / The mind deep into earth.”

To me, the place where Dickinson’s voice most clearly comes through is in your interest in odd, King James Version “biblical” language, which permeates the poem, and gives a sense of people being either unmade by this invading language that no longer can quite describe their experience, or needing this language because its antiquated character—its distance from their spoken language—allows it to carry a set of meanings they can’t access in another way. I’d love for you to talk a bit about how this language found its way in—for example, in passages like: “Bring thy pebble or thy flowers or thy inscription / Bring bring bringeth your love / Dear ones bringeth your love.”

JF: Once I recognized that Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for death” was informing the writing of Gates & Fields, I began to work more consciously with the map of that poem. I noted particular images in it, such as “the Fields of Gazing Grain” that you mentioned, “the Setting Sun,” “The Dews drew quivering and chill,” and wrote with them, extending and plotting them throughout the book to shape a tapestry where these images and others provided the “landmarks” for otherwise destabilized places. You can see a version of Dickinson’s images when I write “The secret eyes of field life / The secret life of wheat gazing / The wind suns itself upon the wheat.” What struck me about the images of nature that appear in Dickinson’s work is that they seem to be doing the looking (“Gazing Grain”) at least as much, if not more, often than they are objects that are looked upon. Then of course, “The Carriage” and “the Horses’ Heads” all figure into Gates & Fields throughout, “A horse might surely tread A path / The wheat wet A shadow-sun / A path might find a horse’s tread.”

What a brilliant notion Dickinson had in making this journey a physical journey with a gentleman suitor of sorts as death’s caller, who Dickinson humors as she notes his “civility.” But to get to your point, I think it’s interesting that the places in Gates & Fields seem to you like actual places unlike in Dickinson’s work. This may be the case. Perhaps in the back of my mind I was thinking of my mother-in-law’s funeral, who died too young from lung cancer. I still hold guilt for not being able to visit her grave. But the little cemetery north of the city was beautiful and held something wild in its constructed space—so many flowers and trees and a small hike up a hill to her grave that I couldn’t conflate the sights with the feelings. I think I’m merging in Gates & Fields “place” with “space,” both physical and mental. In the first two sections of the book, “Gates” and “Fields,” I wanted to specifically investigate burial sites from various angles: the economics, the laws, the rites and the etiquette, the physicality of the constructed social space of a cemetery versus a place where ashes might be strewn, and how “nature” occupies or is occupied in these places.

I love what you wrote about the “invading” “King James Version ‘biblical’ language,” which yes I sourced from Dickinson but also was my attempt to address religion and prayer as I tend to harbor resistance or confusion in these areas. At one point, one of my readers suggested I should cite the sources for this language. The funny thing is that it’s all made up or, more honestly, channeled by some fashion. I don’t come from a religious background nor do I consciously carry such knowledge. But sometimes the highly poetic, the prayer, the meditation is one track that can help us think our thoughts and pain. I knew I wanted several tonal registers in the book, as to me the book is largely about the way we speak, don’t speak, or struggle to speak about death, dying, grief.

MCH: Your framing the question about “the constructed social space of a cemetery versus a place where ashes might be strewn” is intriguing to me, because one of the notes I wrote to myself when I first read your book was “history/etymology of plot.” I was interested in the relation this book frames between language, grieving, space, and time: “Because the carriage was a vehicle for grief that wouldn’t move despite life passing.” This seems like an unplotted poetics, in the sense that plot, or narrative, is a system for measuring change over time. Yet the relation of a grave plot to time—especially one in a well-tended cemetery—is actually about things not changing over time; the grave site stays in a fairly stable state at least as long as anyone who remembers the buried person is still alive. Is that one of the threads you’ve been thinking about here? How do you see this book thinking through questions of time and change?

JF: Well I don’t want to unnecessarily critique a cemetery site as a place for mourning, but I do question its significance at times: who it remains for and if it is a way to otherwise plot or narrate difficult feelings in a more locatable way. Is the grave site the diary, where the narration of one’s younger self is preserved? Of course we’re talking about real bones not words but I do have that question. I’ve found there are several plots that dominate our culture that are signaled as prescribed ways on how to mourn the dead. I’ve actually been told before “You’re still mourning” as if I was inappropriately stuck in the mourning state instead of the memorializing or other part of the trajectory that I should have been. The mourning prescription might appear subtle but it’s there.

I tend to feel uncomfortable with stories, particularly stories about people’s lives. How does one narrate someone or “read” someone? In my first book Holiday, I asked this same question in terms of stories about places, history. The speaker in Holiday indulges in a holiday but resists the typecasting of place via the pushy travel books and the souvenir stands. In that book, I thought about the times one is on a vacation but is too busy imagining how to memorialize it through photographs rather than being present with the actual experience. Susan Sontag’s On Photography speaks a lot to this. And yet I appreciate seeing tree rings and thinking how they document a tree’s life or my hands that are beginning to show time with spots and discoloration. So I’m not afraid so much of thinking about time and change, but I am uneasy about ways we try to do this.

This brings me to mention a fantastic talk I saw the other night through Albert Mobilio’s Double Take series. Writers Idra Novey and Alex Mar spoke about the work of Ana Mendieta and how through a feminist lens she was able to complicate and lay bare some of our ideas about death and dying and our fear of the dead body. I won’t go further right now, but it relates to many of the topics we’ve been discussing. By the way, I’ve been meaning to ask you how your own work aligns with our discussion. I remember at some point you wrote to me that your scholarship is about the afterlives of the enclosure of the commons in Romantic and other poetry.

MCH: Right! I had initially been interested in your book—long before reading it!—because its title seemed so closely related to a lot of the thinking I’ve been doing in my research. My dissertation looks at the ways that authorship—and especially copyright law—is closely entwined with the history of privatized space (in particular, with the English history of the enclosure of village commons, which was at its most widespread around the time of Romanticism). “Fields” (either as common grazing land or as privatized agricultural space) and “gates” (as places where one negotiates a property boundary) are both central terms for me. What I find so exciting about your book is that your use of both “fields” and “gates” is a little helpfully estranging from my general thinking about those words, for example in this beautiful, motion-filled stanza, which maybe I’d ask you to talk a little about, as my final “question” for you:

The gates held the family while the field flew

The gates held the hands that worked the land

The gates held the smaller stones and bigger stones

The field left to grow and over-grow so one field

was layers of fields and fields and fields

JF: Your dissertation sounds great. I remember when you spoke about your research during your visit to one of my Eugene Lang poetry classes—you were discussing this topic in relation to the walks Coleridge and Wordsworth did, which in turn informed The Prelude. In the excerpt that you cite from Gates & Fields, as well as throughout the book, I explore ideas around public and private space. What happens to space when it is privatized, enclosed, gated, versus space that anyone is invited to, space that appears immediately boundless? What does it mean to have a cemetery be a beautiful kind of park but perhaps not being able to picnic there?

This excerpt is about the concept and construction of a cemetery, the people who worked to develop it, the grievers who mourn there and their rituals (e.g in Judaism it is often customary to leave rocks on graves) in contrast to a non-cemetery space, a field, where such markers are not found. The boundless field or what appears as such might give the sense of less resolve, location, versus the more bounded, normalized spaces of cemeteries. Or as the poem right before the one you cite posits: “Might not they both be bookmarks/Might not they both hold our minds as resting place.” I do believe we become more sensitive to physical space when we lose people we have loved. Where did they go? How to make “sense” of this.

MC Hyland

MC Hyland is a PhD candidate in English Literature at New York University, and holds MFAs in Poetry and Book Arts from the University of Alabama. From her research, she produces scholarly and poetic texts, artists’ books, and public art projects. She is the founding editor of DoubleCross Press, a poetry micropress, as well as the author of several poetry chapbooks and the poetry collection Neveragainland (Lowbrow Press, 2010).