How to Make a Unicorn and Other Lost Facts of Animalkind

Elena Passarello on Famous Animals, from Koko the Gorilla to the 'Endlings'

When Elena Passarello was a girl, her grandparents took her to see a unicorn. Lancelot was a “creamed-rinsed, mutant goat with a watery eye,” a “survivor of backwoods surgery with a pastel-bedazzled wang sprouting from his brain.” Like the other children in the audience, Elena was enchanted. She knew Lancelot was a phony, a glitzed-up Frankensteined goat, yet her heart palpitated with the earnest love of a wowed child. In his sparkling eyes, she recognized herself.

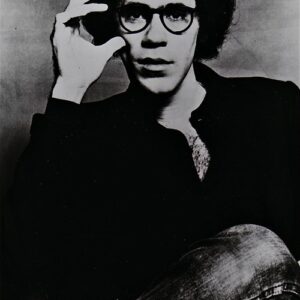

Today, Elena Passarello is a writer, and her second book of essays, Animals Strike Curious Poses is just out from Sarabande. In addition to a meditation on Lancelot, the collection includes 16 essays on the lives, deaths, and mythologies of various other animals. Modeled after a medieval bestiary, the book progresses chronologically, beginning with the story of Yuka, a wooly mammoth frozen in 39,000 B.C. and ending with the 2015 hunting death of Cecil the lion. In between, Passarello considers the pet starling who may have inspired Mozart’s compositions, an Elizabethan-era fighting bear who threw mastiffs into the stands, a Galapagos tortoise’s heartbreak for Charles Darwin, and Arabella, the first spider in space. “We feel the pull of the them before we know to name them, or how to even fully see them,” Passarello writes of the human obsession with animals. “It is as if they were already waiting, crude sketches of themselves, in the recesses of our bodies.”

Over email, Passarello answered my questions about her new book and her thoughts on the changing roles animals play in our lives.

Anya Groner: Your book is concerned with both the actual experiences of specific animals and the role animals occupy in our human imaginations. “Animal images are particularly buried inside us,” you write. “We scratch the arcs of their trunks in the dirt with our feet, or use the sharpest tools available to dig them from shocks of wood. Give us a stick and we’ll draw them.”

How do animal images continue to shape our lives today? Are animals as important to the human experience as they were in the past?

Elena Passarello: It’s easy in 2017 to be a human who never seriously considers or experiences an animal. I can count maybe a dozen instances in which I’ve seen the live animal that became my dinner. Many people carry out entire lives only in contact with pets, urban “pests,” and other humans. According to John Berger, when we experience animals in domestic situations—when we visit zoos or dote on a pet—we’re engaging with animals whose animal-ness was taken from them long ago. We’re basically looking at nothing. Or worse, we’re looking in a mirror.

So I’m interested in the contemporary moments in which animals seem extremely, virulently, important to everyday experience. I have been known to cry uncontrollably at that story of the dog with wheels for back legs. Or the dog that waited outside a Japanese train station for its dead owner to return. These animals are located far from their audiences, but their stories replicate and become crucial. It’s enough to scramble your brain. Here we are in the middle of a mass extinction. Megafauna like Amur tigers and black rhinos are being wiped from existence. Many of us keep no work animals and have only a limited sense of where our food comes from. And yet we’re glued to our computers, watching videos of a rat carrying a slice of pizza down a flight of stairs.

AG: Rather than focusing on whole species, you mostly write about specific animals. Why did you take this approach? What do you gain by focusing on individuals?

EP: When I decided to try to do a whole book of animal essays, I was stuck on the idea of a contemporary bestiary. Medieval bestiaries had single entries for different species, with passages of “facts” about each creature surrounding an (often very inaccurate) illustration. I like all the mis-reportings, which say things like wolves come out of the woods at twilight to steal men’s voices or unicorns can only be caught using a female virgin’s lap for bait. When I began my research, I looked for stories with misuses/misinterpretations of animals to serve various human desires. I also used the bestiary’s tendency to include one entry per creature. There’s only one cat in my book, only one crocodile, one tortoise. I added the restriction that each animal I chose must have a name recorded in the human historical record.

Restraint is only good as long as it’s useful. I couldn’t decide on just one war pigeon, and so that essay involves four pigeons from four different human conflicts. My essay on the horse is actually a quartet of horses: Mister Ed, Clever Hans, Oreo the runaway Central Park carriage horse, and Christopher Reeve’s horse, Bucket. In other essays, the titular animal is a red herring for something else.

AG: One of the most delightful aspects of reading your book was the depth of research and the abundance of bizarre factoids. For example, I learned that not only is it possible to graft the horn-buds of a newborn goat into the frontal bones of the skull to create “a single keratin pillar,” but also that this practice has been used to make real live “unicorns.” What was your research process like?

EP: I first learned about goat surgery via the leg of my dear friend T. Clutch Fleischmann, who had just gotten the patent illustration of that weird procedure as a tattoo. In a way, that essay began on Clutch’s gam.

But in general, my research process is insane. I’ve never found a way to regulate it; I suck it up and jump into the chaos. For my essay about Arabella, the spider who spun webs on Skylab in 1973, I spent a summer looking into the science of web-building, the space race, NASA’s educational programs, the physics of space station life, what a solar flare is, the trouble with measuring distance in space, NASA in-flight transcripts, space patents, etc.

There are lots of facts—entire essays, even—that don’t end up in the book. I was sad to never include the mating habits of Octopus vulgaris, or the story of José, the beaver that showed up in the Bronx River and became BFFs with a muskrat, or the fact that Nikola Tesla was in love with a pigeon that died in his arms.

AG: I’d never before considered how deeply animals were involved in the evolution of human technology. Dogs and elephants were zapped in the development of the electric chair, and a cross spider accompanied astronauts on the United States’ first space station. How is technology, in turn, altering the lives of animals?

EP: I heard an interview on the radio about CRISPR, a genetic editing technique that might allow humans to change the genotypes of living things. Technology could, for example, alter a mosquito so it would no longer be genetically compelled to bite us.

CRISPR is also a part of the science of de-extinction, which doesn’t try using tech to exactly resurrect species as much as to make viable hybrids using material from both long-gone and still-here animals. Perhaps we’ll soon feel a moral obligation to use this technology to replenish the planet. Or perhaps that technology will make us flippant about saying goodbye to entire species, since we could just run to the lab and bring them back.

AG: I was struck by how many points of view you embody in this book. In the first essay, “Yuka,” you inhabit the point of view of a hunter on the steppe, watching a lion attack a wooly mammoth. “Lancelot” is a personal essay and “Harriet” is told in the second person point of view of Charles Darwin’s lovesick pet tortoise.

EP: POV can zoom your reader toward some aspect of the essay or keep them at arm’s length if that’s more serviceable. I often evoke the distant third in the book—like my essay about the terrible history of American circus elephants—when the details of an animal’s history are so overwhelming that they might reroute the piece.

There’s only one essay in the book in which I speak as myself. I am such a flawed and unreliable author for this particular book. I’m no naturalist; I’ve never even been camping. I have a muddy relationship with animals, as perhaps do many Americans of my era. But animals are crucial to me, especially creatively, which is troubling and dangerous. So I wanted to show up for the book and display the problematic place where these essays began.

AG: You also experiment with form, structure, and style. “Jeoffry” is a reimagining of the missing parts of Christopher Smart’s 18th-century poem Jubilate Agno and is written in numbered poetic lines. “Koko” takes the form of a joke and you limit your language to the actual recorded vocabulary of the famous signing gorilla. “Jumbo II” is written as a timeline. How did you settle upon the structure for each essay?

EP: I love how essays can marry research and formal experimentation. The play of those elements is such an engine for thought and practice. I try to use what I call the inquiry of each essay—what it’s doing on top of recounting a famous animal story—to drive the experiments of the piece. The inquiry of “Jeoffry,” for example, considered fragmentation—what it meant to examine chunks of a life, a consciousness, a work of art—as well as the relationship people can have with a silent god. I was researching Kit Smart’s biography, his incomplete asylum epic Jubilate Agno, and the gaps cats fill in our motley lives. When I learned that an entire left side was missing from the “My Cat Jeoffry” poem that so many of us know and love. What’s more, I learned the missing side probably followed a specific antiphonal structure, and I was like, “Shit. I have to finish his poem.”

“Koko” came from the absurdity that my research uncovered. The real story of Koko is more contentious than my childhood idea of her, which was created by children’s books and TV. Learning the truth about Koko frustrated me to the point of an acrid hilarity. “Shit,” I thought. “Why not use the facts of Koko to tell an awful joke?”

AG: Throughout the collection nostalgia recurs for a time when the human animal relationship was less mediated. “Real animals had been extracted from my own here long before I arrived,” you write. “Here for me was but a synthetic wilderness.” In “Celia” you introduce readers to the word “endling,” a term invented to describe the last living survivor of a species. You also write about how zoos maintain sperm and egg banks—“frozen zoos”—in case future scientists decide to bring extinct species back. What other shifts have you noticed in human and animal relationships? What new changes do you anticipate?

EP: I wonder how, as the species dwindle, we’ll change our views of Earth’s heartiest creatures—the squirrels and rats and roaches and pigeons that breed easily and can live anywhere. They adapt as humans change their landscapes and might even outlast us. When we have fewer species, will these ubiquitous animals resonate differently or connote something else? In what new ways might we let them into our homes, our bellies, or our dreams?

AG: You’re currently writing a column for The Paris Review about famous animals in history. Is there another book about animals yet to come?

EP: The PR column has been so fun because it’s allowed me to resurrect a few stories that I’d researched but couldn’t include in the book. But the column and this book might be it for critters. For the next big project, I’m considering writing more about myself.

But now that I think of it, I’m as much a critter as I am anything else, right? So yes. I suppose there is another animal book in my future.

Anya Groner

Anya Groner's writing can be found in journals including The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Oxford American, and Ecotone. She teaches writing at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts and for the New Orleans Writers Workshop. Find out more at www.AnyaGroner.com