Hemingway vs. Ken Russell: Or Why You Should Compare Apples to Oranges

Noah Berlatsky on the Critical Value of Broad Comparisons

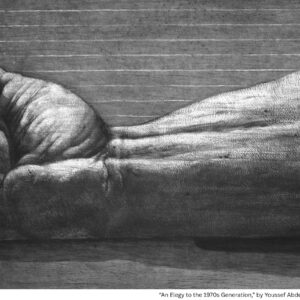

Ken Russell’s 1988 vampire goof Lair of the White Worm is better than Ernest Hemingway’s 1952 classic The Old Man and the Sea. It’s not even much of a contest. Hemingway’s tale is sodden with maudlin masculinity; arm-wrestling matches, outdoor exertion, and sparse repetitive prose testify to the protagonist’s solemn potency. It’s an aggressively simple-minded elegy for manly men doing manly things with fish. Lair of the White Worm takes that wounded but revered phallus, chops it off with a giggle, and gives it a cheerful, forked-tongue lick. Instead of the plodding pedantic self-pity of some man overcoming, Lair gives you Amanda Donohoe in blue body paint with a giant strap on, slithering across the screen as she murders youthful travelers, turns doughy policemen into dancing serpents, and generally demonstrates that camp mockery has more swagger than working-class testosterone. As a penis substitute, a big fish is no match for a giant white worm.

No doubt some misguided souls will disagree with this assessment. Others, perhaps, more willing to compromise, may ask, “Why compare these two things at all?” A book of serious literary fiction and a horror/comedy film created more than three decades apart: they have different audiences, different themes, different intended goals, different approaches. Why not appreciate each for its own peculiar virtues: The Old Man and the Sea for its stoic sentimentality; Lair of the White Worm for its arch entendres that aren’t even double? It’s like comparing apples and oranges.

Of course, comparing apples and oranges isn’t all that difficult to do for most people—I like apples better, myself. When people say that you shouldn’t compare, say, Fantastic Four comics to The Importance of Being Earnest, they don’t mean that such comparisons are impossible. Instead, they mean that such comparisons are unfair. Putting an apple next to an orange results in the invidious, possibly elitist devaluation of oranges, and an insufficiently refined appreciation of the essence of orangeness. Thus cartoonist Eddie Campbell, in an essay for The Comics Journal from a while back, takes to task critics who argue that the classic MAD comics are not as good as literature.

…the question is, would we want to be stuck in it with some guy who would ask: Since we already have Aristophanes, who needs Kurtzman? Since we have Erasmus of Rotterdam, why would we want Steve Martin? With Wagner still available, who cares about the Firehouse Five? Furthermore, would we let that guy organize the party music?

What appears at first to be taking a more stringent view is in fact applying irrelevant criteria. It dismantles the idea of a comic and leaves the parts hopelessly undone.

To compare comics to literature is, for Campbell, to cut comics apart, and leave out the bit that makes them comics. It does violence to the art, and leaves you knowing less about the orange than you did before.

The resistance to comparison is often a subset of the resistance to criticism in general, rooted in concern that analysis and evaluation will damage the analyzed and evaluated. As a quote often attributed to Elvis Costello has it, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” Juxtaposing different things results, not in insight, but in intellectual and even spiritual confusion. Critics who attempt to squish disparate things together into one snowball threaten to tarnish the uniqueness of each separate snowflake. “It is important to keep in mind that film and literature are two different art forms that offer different experiences,” as Siobhan Calafiore writes at The Artifice. “They both have their pros and cons. It is possible to enjoy both experiences if we keep an open mind and let each method of story telling speak for itself.”

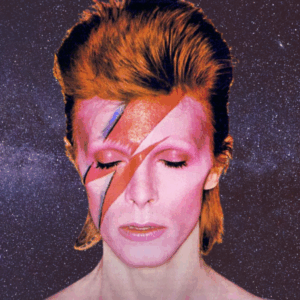

But does art itself keep to this model of purity, with each aesthetic experience carefully separated and kept in its place? The answer is, of course not. Artists are heterogenous magpies who mix and borrow with abandon. Almost every other film it seems is based on a novel or printed source—Calafiore’s article, in fact, is about film adaptations. Eddie Campbell’s beloved comic books mash together words and images. Bob Dylan lifted tricks from the Beat poets, Maya Angelou borrowed from the blues, Howling Wolf got his howl from country musician Jimmie Rodgers’ yodel. Hip hop chops up and reconstitutes samples of other music, Lichtenstein chopped up and rejiggered comics (much to the irritation of many comic artists). Art regularly crosses boundaries of medium and genre. I’m sure somewhere out there someone has created a dance about architecture—why not?

Art finds meaning, humor, excitement, and surprise in juxtapositions and comparisons—whether it’s Jane Austen deflating gothic horror with comedy of manners in Northanger Abbey or Robert Rodriguez inflating a heist film with vampire splatter in Planet Terror. And, similarly, criticism can find meaning, interest, humor, and insight in putting two seemingly disparate things next to each other and thinking about how they fit together, or how they don’t. Is The Wire like Greek tragedy? Are superheroes modern myths? Is your selfie comparable to Rembrandt’s self portraits? The answer in each case is in some ways yes, in some ways not so much—but the differences and similarities lead you to ideas, and aesthetic perspectives, you might not have had otherwise.

One’s experience of art is always linked to one’s experience of other art. Artwork relies on tropes, genres, and prior knowledge—Twilight‘s sparkly vampires that can run around outdoors in the daylight rely for part of their effect on a knowledge of all those screen vampires who burn up when exposed to sunlight. Twilight‘s denouement, in which the big battle with the evil villains is abandoned in favor of an uneasy truce, depends on a familiarity with all those action movies where the climax is an orgy of violence and explosion and death. So, if you wanted, you could compare Twilight to Nosferatu—or you could compare it to James Bond.

James Bond films of course are meant to provide you with the exhilaration of conflict and violent spectacle; to question that is to question the very basis of the film. And that’s exactly why comparisons, and especially apples to oranges comparisons, can be meaningful. When you compare two similar aesthetic things—say, the latest Captain America movie to the latest X-Men movie—you end up taking a lot for granted. Good guys wear masks and beat people up; without a broader comparison, this is the way the world always works. There’s no alternative.

When you’re willing to make broader comparisons, though, you can end up seeing options, and choices, and patterns that you might not otherwise see. Maybe good guys don’t have to wear masks and beat up people. Maybe you could have a world in which manliness and heroism involve someone without superpowers pitting themselves against the elements in a test of skill and strength, as in The Old Man and The Sea. Or, maybe, heroism and manliness are both elaborate, campy jokes, and it would be more fun to root for the snake goddess to eat them both, as in The Lair of the White Worm. Whether art is bad or good or better depends, not just on whether it succeeds within the boundaries it sets for itself, but on whether those boundaries are well chosen, or foolish, beautiful or ugly, virtuous or morally contemptible. Is Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a ‘Changin’ better than Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing? It depends on whether you think politics in art should be generalized or specific, utopian or apocalyptic. But putting the two together makes you choose—and so forces you to interrogate the art, and your own opinions, with more care than you would have if you hadn’t brought them together.

Part of the excitement, and joy, of art is the opportunity to see other possibilities and other potentials. And that’s the excitement, and joy, of criticism too—whether you’re preparing to eat apples, or oranges, or kiwi, or some strange, unknown, misshapen fruit, that combines all of them, and is better than each.

Noah Berlatsky

Noah Berlatsky edits the online comics-and-culture website The Hooded Utilitarian and is the author of the book Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-48.