SCENES FROM THE LIBYAN CIVIL WAR

The chief government minder’s announcements would come without warning, interrupting the loud elevator music that played non-stop through the intercom system of the luxurious Tripoli al-Nasr Rixos Hotel. “To all journalists: NATO has bombed an apartment building. Martyrs are still under the rubble. A bus will be leaving in five minutes. To all journalists: gather in the lobby immediately.”

We were only allowed to move in herds, like children on a field trip, unsure of where we were going or why, but ecstatic at the opportunity to get out of the hotel. These outings were brief and led by a nervous cast of regime minders working from a rigorous script, guiding us through a parallel reality of fear and deception in which everyone we met referred to Qaddafi by the name he had grandly bestowed upon himself: “Our Dear Brother Leader.”

There was no limit to the range and peculiarity of the propaganda we were fed. One day, in the coastal town of Zlitan, we were taken on a tour of a hospital presumably hit by an errant NATO airstrike, causing mass casualties among the bed-ridden patients. We were asked to film the scene: a meticulously positioned bed, broken and half-covered in rubble; and synthetic blood-red streaks splashed over the bed sheets, all part of an unimaginative effort to convince us that a defenseless innocent civilian had perished there. A New York Times investigation later found credible accounts of dozens of civilians killed by errant NATO bombs in many distinct attacks in Libya, but never in this hospital in Zlitan.

Day after day, we longed for a genuine encounter, a wink, or a murmur from a brave stranger, any sign that would remind us that not everyone was an accomplice. After the initial wave of defections, only rumors dared to challenge the regime’s narrative. There were unconfirmed reports of anti-regime vandalism on the east side of the city; or gossip about Qaddafi’s daughter Aysha’s attempt to flee to Malta, only to be turned back. One morning in March, the wall of deception suddenly cracked, and the brutality of Qaddafi’s security forces was revealed for all of us to see. It was breakfast time at the Rixos when Iman al-Obeidi, a female Libyan graduate student, entered the hotel and walked straight into the restaurant where she knew the journalists were. Her face was dirty and her eyes puffy from crying. Her long, uncovered hair was messy, and her clothes were disheveled as if she had been sleeping in them for days. Iman scanned the dining room and walked straight to a table where a western female reporter was sitting, perhaps thinking that another woman would better grasp the gruesome nature of what she was about to say. Screaming for everyone to hear, she recounted how Qaddafi’s security forces had detained her for two days, during which she was tied up, urinated and defecated upon, and raped by 15 men, some of whom had videotaped the attack.

The disturbance in the restaurant caught the minders off guard. The hotel staff reacted first, including waitresses and a Moroccan female barista armed with kitchen knives, rushing in to restrain Iman and push back the journalists that had gathered around her to film the scene. When a group of minders arrived to take Iman, a huge scuffle ensued. Punches were thrown, cameras broken, and at least one gun was pointed at a journalist. Iman was eventually dragged from the hotel and driven out in an unmarked car. The episode was broadcast as breaking news around the world, and Iman became an instant cause célèbre, the personification of defiance against the Qaddafi regime. Meanwhile, the Libyan Revolution took its course, and the country succumbed to a particularly vicious kind of civil war. Qaddafi himself was eventually captured, tortured, and killed on the spot by a mob of rebels who had found him. The killing was captured on cell phone cameras and the videos went viral, filled with images so grisly that it was hard to believe they were true. To silence any doubters, Qaddafi’s mutilated corpse was displayed to the public for days in a meat locker in the rebel-held city of Misrata. About a year later, I read that Iman had managed to leave the country and was granted asylum in Boulder, Colorado. In 2014, a local newspaper reported on her turbulent adjustment to her new life in America, detailing her multiple run-ins with the law, including her second arrest in as many months for violating the terms of her probation from a previous 2013 assault conviction. A reporter for the Boulder Daily Camera covered her travails. “Rather than have a probation violation hearing, (Iman) Ali admitted to the violation in exchange for the work release sentence,” the reporter wrote. “Ali will remain in custody until a space opens up in the Boulder County Jail’s work release program.”

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. A rebel yells “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) during close-quarters fighting in Aleppo’s Old City.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. A rebel yells “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) during close-quarters fighting in Aleppo’s Old City.

Left: Cairo, Egypt. December, 2013. The Pyramids of Giza. Right: Cairo, Egypt. December, 2013. The edge of New Cairo where it meets the desert.

Left: Cairo, Egypt. December, 2013. The Pyramids of Giza. Right: Cairo, Egypt. December, 2013. The edge of New Cairo where it meets the desert.

Cairo, Egypt. December, 2013. Men collect scrap metal from burned vehicles damaged during the Rabaa massacre of supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Cairo, Egypt. December, 2013. Men collect scrap metal from burned vehicles damaged during the Rabaa massacre of supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Ismailia, Egypt. April, 2011. Photograph of Mohamad Mashour while in jail. He was released in 2011 after serving a 10-year sentence for being an Islamist.

Ismailia, Egypt. April, 2011. Photograph of Mohamad Mashour while in jail. He was released in 2011 after serving a 10-year sentence for being an Islamist.

Zlitan, Libya. March, 2011. Fake blood spilled in a hospital bed at the site of an alleged NATO airstrike in the city of Zlitan.

Zlitan, Libya. March, 2011. Fake blood spilled in a hospital bed at the site of an alleged NATO airstrike in the city of Zlitan.

Tripoli, Libya. February, 2011. Qaddafi supporter.

Tripoli, Libya. February, 2011. Qaddafi supporter.

Zawiyah, Libya. February, 2011. Anti-Qaddafi rebel fighter.

Zawiyah, Libya. February, 2011. Anti-Qaddafi rebel fighter.

AT THE EDGE OF ISIS

My friend Jamal and I had been waiting for hours at a peshmerga base for permission to accompany the mission, but at the last moment we were told that only one of us would be allowed to board the helicopter. Alissa and Adam, two old friends from the New York Times, were already strapped in the seats when I finally boarded, and I remember feeling bad for having to leave Jamal behind.

It was a risky 40-minute flight across Islamic State territory aboard a worn-out Iraqi Air Force helicopter. The goal was to reach Mount Sinjar and deliver bottled water, bread, bananas, and hygiene kits to the thousands of helpless Yezidis stranded there, and to pick up a small group of sick children and old people in need of immediate medical attention.

In August 2014, the rapid advance of Islamic State fighters from Syria into parts of northern Iraq had forced the mass exodus of the local Yezidi population, a religious minority that has lived in this border region for centuries. Threatened with genocide and surrounded on three sides, thousands of Yezidis sought refugee in Mount Sinjar, a mountain range with inter-connecting valleys that has offered them a natural sanctuary during past periods of conflict.

The mountain range came into view, a spectacular sight, surging skywards, abruptly, amid the vast desert badlands that separate Syria and Iraq. As we flew lower toward the landing zone, the scale of the tragedy became apparent. Hundreds of miniature figures dotted the bare mountain top, some of them motionless, others running in our general direction, their faces and desperate gestures calling for help and coming into focus as the helicopter set down, in a storm of noise and dust.

A crowd surged towards the helicopter, held back by a few armed Kurdish fighters. As soon as we touched the ground, I jumped off and started taking pictures. Desperate women holding on to their infants, an old man on crutches, several unaccompanied children, and more than a dozen others pushed their way past the crew and into the doomed chopper. The deafening noise of the rotors overpowered every other sound, creating the bizarre sensation that everything moved in slow motion. The two pilots, unable to keep the situation under control, ordered their men to cut the mission short, and prepare for a hasty lift-off.

I fought my way back inside the helicopter, and managed to stand on a bench holding on to the fuselage next to Adam, both of us struggling to keep our balance while photographing the drama around us. Seconds before being airborne, a frantic crew member forced two Yezidis off the chopper at gunpoint, but the helicopter was still dangerously overweight. I don’t remember the precise moment we took off, or how soon after the helicopter went down. All my senses were focused on taking pictures. In the moment of impact, I closed my eyes, and for a split second the world went silent, as if someone had suddenly pressed the mute button at the height of a thunderous drum solo. There was no flash of life before my eyes, not a chance to say goodbye, just the most solitary moment I have ever experienced.

Sinjar, Iraq. August, 2014. Injured survivors of a helicopter crash in Mount Sinjar are evacuated to safety in an Iraqi Air Force rescue helicopter.

Sinjar, Iraq. August, 2014. Injured survivors of a helicopter crash in Mount Sinjar are evacuated to safety in an Iraqi Air Force rescue helicopter.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. A rebel fighter takes cover inside a school during fighting between rebel forces and regime soldiers in Aleppo.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. A rebel fighter takes cover inside a school during fighting between rebel forces and regime soldiers in Aleppo.

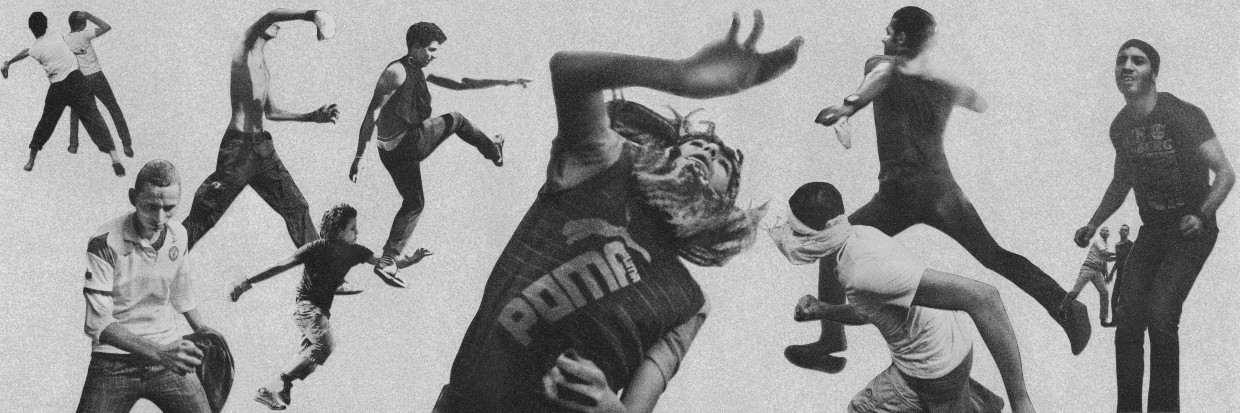

Cairo, Egypt. September, 2012. Clashes near the American Embassy.

Cairo, Egypt. September, 2012. Clashes near the American Embassy.

Al Nazla, Egypt. August, 2013. The Virgin Mary church in the village of Al Nazla, burned and looted by an Islamist mob during an episode of sectarian violence in Egypt.

Al Nazla, Egypt. August, 2013. The Virgin Mary church in the village of Al Nazla, burned and looted by an Islamist mob during an episode of sectarian violence in Egypt.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. Searching for survivors in the aftermath of bombardment by regime warplanes in a rebel-held residential district in Aleppo.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. Searching for survivors in the aftermath of bombardment by regime warplanes in a rebel-held residential district in Aleppo.

Cairo, Egypt. January, 2013. A woman involved in clashes near the Intercontinental Hotel.

Cairo, Egypt. January, 2013. A woman involved in clashes near the Intercontinental Hotel.

Cairo, Egypt. November, 2011. A young man with the head of a goat, slaughtered during an Eid celebration in the Shobra district of Cairo.

Cairo, Egypt. November, 2011. A young man with the head of a goat, slaughtered during an Eid celebration in the Shobra district of Cairo.

Marae, Syria. July, 2012. The torso and back of Zakariyya Gazmouz, a suspected Shabiha prisoner, his body covered in pro-Assad tattoos that he later defaced with a razor.

Marae, Syria. July, 2012. The torso and back of Zakariyya Gazmouz, a suspected Shabiha prisoner, his body covered in pro-Assad tattoos that he later defaced with a razor.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. A makeshift swing made with a plastic chair found inside a mosque that was occupied by Syrian Army soldiers on the Salahaddin front line in Aleppo.

Aleppo, Syria. March, 2013. A makeshift swing made with a plastic chair found inside a mosque that was occupied by Syrian Army soldiers on the Salahaddin front line in Aleppo.

ENCOUNTER WITH AN ASSAD LOYALIST

Zakariyya Gazmouz stood out. He was younger than the other prisoners, and his shaved head clashed with his bushy black beard, accentuating the fresh bruises around his big eyes and forehead. His gaze was passionate, his manner serene, and he conducted himself with the peculiar calm of a defeated man.

Zakariyya was being held inside a high school converted into a temporary prison in the rebel-held town of Marae, a safe distance north of the urban battlefield of Aleppo, where a few days earlier he had turned himself in at a rebel checkpoint. The reason for his surrender was unclear, but he confessed to being a police informer working for the regime, a job he said helped support his drug addiction. The rebels arrested him on the spot and accused him of being a shabiha, a member of the feared gang of Assad loyalists responsible for most of the killing and torture at the time.

The rebel in charge of the prison, who went by the name Jumbo, was thrilled to have Zakariyya among his captives, and was eager to show him off. We sat in the principal’s office that doubled as Jumbo’s headquarters one day, when a guard brought in Zakariyya, disoriented, barefoot and handcuffed. Jumbo greeted his prisoner with an exaggerated grin, casually putting an arm around him, as a friend would. Jumbo proceeded to lift Zakariyya’s shirt over his head, revealing his heavily tattooed upper body. Front and back, there were representations of women’s faces, swords, tigers, a pair of flowers. The faces of Bashar al-Assad and his brothers, Hafez and Basil, arranged in a holy trinity, had been disfigured by fresh grisly gashes. Blood trickled down Zakariyya’s tattooed belly, where more gashes defaced an inked Arabic poem praising Assad and Hassan Nasrallah.

Zakariyya explained that his wounds were self-inflicted, made in a desperate attempt to demonstrate that he no longer believed in the regime, and that he was prepared to donate blood as a fealty to the rebels. The rebels who arrested him had beat him for days, and he still bore large purple bruises all over his back. Before sending Zakariyya back to his cell, Jumbo tried to show us his softer side, and in a gesture of compassion, [he] allowed Zakariyya to make his first phone call since his arrest. Nearly in tears, Zakariyya called his mother to tell her he was alive.

I left Marae a few days later, wondering what more there was to Zakariyya’s story and reflecting on the fine line between victim and perpetrator. I never saw him again, but his scars continue to haunt me. I see them replicated in the disfigured facade of buildings in war-torn districts of Aleppo. I am reminded of them when I hear the victims’ accounts of massacres, executions, rape, and ethnic cleansing, multiple testimonies that merge into a single narrative, one that amounts to slightly different versions of the same horror.

Essay and photographs excerpted from Discordia which can be found at www.discordiathebook.com.

Moises Saman

Moises Saman is documentary photographer and a member of Magnum Photos. His most recent body of work, Discordia, is a visual account of the Arab Spring, made up of work compiled over four years spent living in the Middle East. The work featured in Discordia has received numerous awards, including the 2015 Guggenheim Grant for Photography, the Eugene Smith Memorial Fund (2014), the Henri Nannen Preis (2014), the World Press Photo (2014), and Pictures of the Year International (2012, 2014, 2015). Moises is currently a regular contributor to The New Yorker Magazine, TIME Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, among other international magazines.