Five Books Making News This Week: Critics, Gods, and Single Ladies

Matt Gallagher, Rebecca Traister, Nayomi Munaweera, and More

Oscar night is literary this year, shining a spotlight on thirteen films based on books–Academy Award nominees The Revenant (Michael Punke), Brooklyn (Colm Tóibín), The Big Short (Michael Lewis), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Room(Emma Donoghue), The Martian (Andy Weir), The Danish Girl (Michael Ebersoff), Steve Jobs (Walter Isaacson), Embrace of the Serpent, Colombia’s foreign film entry (Richard Evans Schulte), the story “45 Years” from In Another Country (David Constantine), Bridge of Spies (Giles Whittelland), Trumbo (Bruce Cook), and, yes, for best song, The Weeknd’s “Earned It,” from Fifty Shades of Gray (E.L. James). The week also brings cheers for Iraqi War veteran Matt Gallagher’s first novel, Nayomi Munaweera’s second, Rebecca Traister’s analysis of a new category of American citizen, and Susan Jacoby’s secular history of conversion. And more critics take on A.O. Scott’s treatise on criticism.

Matt Gallagher, Youngblood

Vanity Fair included Gallagher among the contemporary writers who echo the modernist poets who arose out of World War I—“an elegant echo: a new literature emerging from a new fight. Like their predecessors, these men are veterans, some having served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan over multiple years.” Gallagher launched a popular blog from inside the Iraqi war in 2007, expanded it into his nonfiction book Kaboom. His first novel transforms his experience at war into fiction, with complex results that draw critical praise. He talked about Youngbood with author Phil Klay (Electric Literature).

“Everyone who reads war lit knows Matt Gallagher,” notes Roxana Robinson (Washington Post). “Gallagher began writing about the war in Iraq from inside it….While his nonfiction was visceral, immediate and reportorial, his fiction transforms direct experience into something more layered and complex…In Youngblood, Matt Gallagher shows again how war works in the human heart—something we’ll need to know, as long as there is war.”

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) calls Youngblood “urgent and deeply moving.” On one level, she writes, “the novel is a parable—with overtones of Graham Greene’sThe Quiet American—about the United States and Iraq and the still unfurling consequences of the war. On another, it’s a story about how we tell stories to friends and strangers, trying to convey experiences they will never know firsthand, and how we tell ourselves stories to reckon with the past—or, perhaps, to live with painful memories that are difficult, if not impossible, to assuage.”

Nayomi Munaweera, What Lies Between Us

Munaweera, who was born in Sri Lanka, raised in Nigeria and now lives in Northern California, won the Commonwealth Book Prize for the Asian Region in 2013 for Island of a Thousand Mirrors. Her powerful new novel draws applause from critics. (She reports from Sri Lanka’ Galle Literary Festival here.)

“Trauma is rarely captured in literary form with as much fiery intensity as it is in Nayomi Munaweera’s devastating second novel,” writes Anita Felicelli (San Francisco Chronicle). “The opening pages foreshadow the brutality to come by evoking the dark tale of a monstrous mother moon bear and explaining that this is the story of an incarcerated mother, not named until the final page. It’s a testament to the power of Munaweera’s dazzling, no-holds-barred storytelling that the novel’s climax still feels shocking.”

“The novel is rich with artfully intricate language and descriptions,” notes Bianca Torres (Seattle Times). “Munaweera has managed to craft an alluring, complex and beautiful tale centered on a heinous act. While it’s clear a tragic ending is inevitable, the novel carries an urgency and hypnotism that makes it impossible to look away.”

Susan Jacoby, Strange Gods: A Secular History of Conversion

More than half of Americans will change religions in the course of a lifetime, journalist Susan Jacoby tells NPR’s Fresh Air. Jacoby, who is an atheist raised by a father who converted from Judaism to Catholicism, explores explores a history of conversions, through force and persuasion, in her new book.

“Strange Gods, with its scope (Augustine of Hippo to Muhammad Ali), insight, and carefully assessed judgments, emerges as an engaging rumination on—if not quite a history of—[the] tricky and multifarious subject” of religious conversion, notes Rayyan al-Shawaf (Christian Science Monitor). The terrible reality, he concludes, “is that freedom of thought, conscience, and religion remains elusive for millions of believers and non-believers around the world, including but not limited to ex or heterodox or non-Muslims in many countries where Islam holds sway, and non-state-sanctioned adherents of virtually any religion in China.”

“One of the strongest observations of Jacoby’s book is that persuasion and force as factors for changing somebody’s faith began to become sidelined as a result of the Enlightenment, after which, even among the faithful, organized religions inched away from revealed codas and closer to sets of ideas—although Jacoby, very appealingly, is always sympathetic to the very real personal allure those sets of ideas could have,” writes Steve Donoghue (Open Letters Monthly).

Gary Wills (New York Times Book Review) is not convinced. “Jacoby cannot admit there ever is such a thing as genuine spiritual conversion,” he writes. “She justifiably spends a lot of time on the crueler forms of compulsion, which recur distressingly often in history. But she thinks that all conversions are coerced, however softly or subtly…Looking back over Jacoby’s cast of characters, I hear Peggy Lee: ‘Is that all there is?’”

Rebecca Traister, All the Single Ladies

An award-winning New York magazine journalist turns her focus on the influence of unmarried women on American culture through the decades. In this adapted excerpt, she argues that single women are this year’s most powerful voters.

“Though Traister is no longer one of us, she retains her memories and her empathy, as well as her feminist commitments,” writes Julia M. Klein (Chicago Tribune). “Drawing on, historical and contemporary sources, as well as her own reporting, she has produced a wide-ranging, insistently optimistic analysis of the role of single women in American society. Among the topics she covers are the power of female friendship, the diversity of attitudes towards sex, alternate paths to parenthood and the special challenges encountered by poor women and women of color.”

Rebecca Carroll (Los Angeles Times) points out the origins of Traister’s title: “Beyoncé herself, although no longer a single lady, has never more than now marched into the extant fray of sexuality and gender politics with guns blazing. And as a black woman who lived well into her adult life as a single lady (I married at 34), I was surprised to find that this book was talking directly to me — a rare thing in mainstream works by white authors examining the lives of women in America.” Carroll concludes, “…the exemplary framework of cultural inclusion, the personal candor and palpable desire to lift up each and every one of us, is what makes All the Single Ladies a singularly triumphant work of women presented in beautiful formation.”

Rebecca Steinitz (Boston Globe) calls Traister’s book “an invigorating defense of a demographic too often criticized and caricatured, rather than recognized for its profound effect on American society.” The first two chapters, Steinitz writes, “make a powerful and convincing argument that women and especially single women—independent, ambitious, free from the constraints of marriage and children — have ‘helped to drive social progress of this country since its founding.’”

A.O. Scott, Better Living through Criticism

Why be a critic? And what is criticism anyway? Critics take on a critic’s book on criticism, Part II. (Part I.)

Dan Fox (Los Angeles Times) goes all playful: “Behold the ouroboros! A book about criticism written by a movie critic and criticized here by an art critic. It’s a setup so potentially repellent that this review could almost be subtitled “The Human Centipede.” After all, we critics are reputedly the bottom-feeders of the arts. Scavengers picking over the earnest toils of goodly creative people.” Seriously, he concludes:

If Better Living Through Criticism occasionally comes off as defensive, a little trigger happy in anticipating the counter-arguments to his ideas, for the most part reading Scott’s book is like watching the stiff-upper-lipped hero of a British 1940s thriller facing down his or her adversaries—modest, brave and utterly unflappable. I’d say that’s a pretty good model for a critic.

Daniel Mendelsohn (New York Times Book Review) is skeptical of Scott’s “faux-populist diction,” which, he writes, “doesn’t reflect this author’s real allegiances, which are evident in the works he selects for his loving and expert analyses: Rilke and Philip Larkin, Picasso and Henry James.” But he’s generally favorable:

Whatever its occasional pandering, Better Living Through Criticism mostly exemplifies the rhetorical virtues it so enthusiastically celebrates as being peculiar to the critic: attentiveness to detail, alertness to context, a hunger for larger meanings. The critic, Scott declares in the book’s final dialogue, is “a person whose interest can help activate the interest of others.” In an era of reflexive contempt for erudition, taste and authority, qualities that Scott is perhaps too hesitant to name as the sine qua non of great critics, it is no mean feat to help activate, as this book will surely do, an interest in the genre of which he and others of his generation may be the last professional practitioners.

Beth Kephart (Chicago Tribune) puts Scott on the spot:

Scott is smart, affable, self-effacing; he rarely puts his own gorgeous film reviewing on display. He suggests but doesn’t insist. He runs his well-traveled mind around the questions—what is criticism? what role does it serve?—and finds the whole thing harder than, he professes, he’d predicted it would be when he set out to write the book. With so many others weighing in (via Scott) on the role and responsibilities of the critic, with Sontag suggesting, in Scott’s words, that “the right way to do criticism…is not to do it,” with the critic being lambasted and ridiculed at a somewhat dizzying pace, then rescued, then harried again, readers might find themselves awash in—well it’s not always clear precisely what—or if all of this is leading toward the promised better living.

“The book might best be seen as an inspirational cultural-studies primer,” notes Lawrence Levi (Newsday). “Its intended audience seems to be the generation weaned on Amazon reviews, Rotten Tomatoes and Yelp, young people who may be puzzled by the notion of professional criticism in an era when everyone truly is a critic.”

Nathan Heller (The New Yorker) asks, “What’s the point of a reviewer in an age when everyone reviews? A common defense of the endeavor centers on three qualities: expertise, eloquence, and attention. Critics have essential skills that Blogging Bob does not. They know more. They are decent writers, who can give a fair encapsulation of a work and detail their responses. And they’re focussed: since their job is studying and explaining the object at hand, they are especially alert to its nuances.”

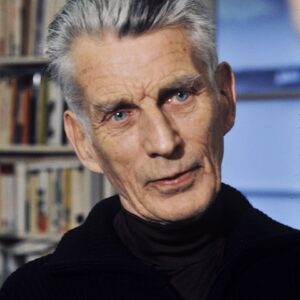

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.