Men with Plain Names

By October, there was a killer on the loose. Five dead the first day. Several more each day after that. And no one was surprised, either. This was the new normal in late capitalist, pre-revolutionary America.

I was working for a man named Mike, helping him paint a one-story apartment building orange. Working outside on ladders, standing in the open, we were easy targets for a man with a gun. I could’ve been back in school, but Mike really had to be here. It was his truck, and his paint, and his job. Mike had a girlfriend at home who was pregnant with a baby boy they were thinking of calling Michael. Just like his name. Just like my name. I tried to talk him out of this, of course, but it was no use.

As we worked we listened to the classic rock station where they almost never talked about anything real, and certainly not the Beltway Sniper. These were the radio voices in your nightmares. Upbeat. Impersonal. Commercialized. They were not being maudlin or ironic when they played “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” for the third time in a day. This was just part of another all-new, nonstop, workday rock-block.

We knew that our faithful disc jockeys would not condescend to listing off the totals of the dead or mentioning the manhunt. They didn’t pander by offering us any updates or breaking news. They didn’t tell us when the Terror Alert level was raised from yellow to orange to red. They just kept their heads down and played the hits: schlocky, feel-good rock and roll.

* * * *

Things were looking up for me, though. I’d actually inherited my father’s car that morning. A blue Toyota Camry. It was just sitting there in front of my house when I came down the steps with my bicycle. I knew the car was my father’s because I could see my brother sitting in the front seat.

“Hello, young man,” I said cheerfully, as he got out, wearing a necktie. “Are you here to tell me about the Bible?”

“Shut up,” he said. “Let me inside the house.”

But I was already out in the street, pacing around the Camry. This car was a beautiful thing to me. It never even occurred to me to ask my parents to bring it down.

“Have you had this here the whole time?”

I knew my brother was around, of course. Right there at the end of the Green Line. My parents had driven him down to the University of Maryland at the end of August. The three of them spent the weekend in a hotel, getting him settled. They drove into the city, where I met them for dinner, twice. And that was the last that I saw of my baby brother.

“I meant to come and visit you,” I said. “I’ve just been busy.”

He nodded cautiously.

“This is good, though. You’ve done the right thing bringing this to me.” I slapped my palm down on the top of the car. My brother didn’t say a word.

“What is all this shit anyway?” I was cupping my hands and peering through the back windows. The seats were filled with boxes and bags. I could see a matte-black stereo and a nineteen-inch television set.

“I got kicked out of the dorms. I need to stay with you.”

“You got kicked out of school?”

“No. Just the dorms.”

“In five weeks? That must be some kind of record.”

“I seriously doubt that,” he said blankly.

I straightened myself up again to stare at him in judgment. Glaring at his stupid necktie. “What did you do?”

“I didn’t do anything.”

“Why are you wearing that tie, then?”

“Because I want to. Jesus Christ. Are you gonna let me inside the house or not?” I could hear the strain in his voice now. “Three more people were killed last night. Did you even know that?”

“Yeah, sure . . . I know,” I said absently. I was still marveling at the car. “You’ve really had this here the whole time?”

My brother frowned. Crossing and uncrossing his arms. He was glancing out toward the intersection warily.

“I almost died in this car, you know? I was driving drunk on my birthday and I spun the fucking thing around backward like—”

“Can we please just get off the street,” he asked me for the third time. “Please!”

“Sure,” I said, passing him my bicycle. “Bring this into the house. I’m taking the car.”

“Taking it where?”

“To work,” I said. “Where do you think?”

“Don’t you have school?”

“Don’t you?”

My brother sighed and handed me the car keys.

* * * *

There was a killer on the loose. These are the plots of horror films. Or crime thrillers. Or just some bad buddy-cop movie. We didn’t know what was going on, which is different than being surprised by it. We had grown accustomed to a world of sudden, randomized death. Literally anything might happen next.

The news reported that the Sniper had been seen fleeing in a white van. Strangers would repeat this to you eagerly. We made a game of pointing them out to each other. White vans were everywhere now. Was this a thing that people already knew, or had the Sniper brought this fact to bear? His was a vehicle chosen for its indistinctiveness. Its ubiquity. Its absence of shape and color. It was astonishing to realize just how many people made their living driving white vans through the city.

As often as not, he was killing in broad daylight, too. People died outside strip malls and parking lots. Places they never wanted to go to in the first place. They were killed in front of gas stations and grocery stores. Running errands and waiting at bus stops. Understandably, the whole thing made people crazy. It became harder and harder not to fixate on the white van. It was the only thing we had to go on.

People wanted warnings. They wanted a fighting chance. They wanted signs that they could see and understand. If only a flock of birds would leap out of the treetops, in the seconds before he squeezed the trigger, we would know to hit the ground. Even just the glinting mirror of a rifle sight could count as something.

As a community, we had yet to produce even one credible police sketch of the killer. Who were we supposed to look for? A man? Someone with a story? A person with a past? We were still just looking for a man now, right? Somewhere among the ten thousand white vans was a person with a gun. Feeling the same heat that you felt, breathing in the same air. I imagined him driving with the windows down, his seat belt left dangling at his side. He was just a blank and smiling face. The only truly carefree man in three states.

The white van itself could never have come as much of a surprise, though. Ghosts have always worn white, traditionally. Flashing in the dark. Floating through walls. In gunfire and bloodshed he was there. In everything else, he might as well have never existed. The Sniper was a terror. A cipher. A blank.

* * * *

I came home from work to find my brother watching CNN. I could tell right away that he’d had it on all day. Staring back at me with this haunted look. Worse, he was still wearing the tie.

As soon as he saw me, he stood up and started following me through the downstairs of the house, telling me that two more people had been shot in the parking lot of a Michaels Craft Store.

“So what?” I asked.

“So isn’t that weird? He keeps shooting people in front of these Michaels Craft Stores. Why there?”

“Why anywhere?” I asked, exasperated.

I told him to stop counting deaths. I told him to turn off the TV and go outside. I told him to go back to school now. To go home. To stop hiding. There was no grand conclusion to draw from all of this. It just was.

“And take off that fucking tie.”

“No,” he said, stepping backward.

“What does it mean?”

“It doesn’t mean anything.”

“Do you work at a bank?”

“What?”

“Are you a Jehovah’s Witness?”

“Shut up.”

“Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the so-called Republican Party?” I asked, getting right up in his face.

“Fuck off.”

“Have you ever knowingly consorted with any so-called Republicans?”

“It’s just a tie!” he snapped as he walked away.

“That’s not an answer,” I said. “That’s evasion. I’m keeping my eye on you.”

* * * *

All in all, I had a car. More than a car, really, I had a birthright. The blue Camry had always been a thing that was rightfully mine, and I was hell-bent on keeping it now. I was the eldest son, of course. Mine was a condition beyond reproof.

Plus, it was fun just to drive. Ripping through the city with the windows down and the radio up. I laid on the horn as I rocketed past every white van I could find. Looking up and laughing at all these startled faces. A young man with a car can do whatever he wants. Go wherever he wants. Even with a killer on the loose. This is the stuff of a thousand classic rock songs. I was going too fast to be killed now.

Mike and I hadn’t always listened to this music while we worked, though. Back in August, after I’d quit my data-entry job and joined him painting apartments, we were devoted listeners of NPR. These marathon runs with the radio going eight hours a day, until we could practically recite the news breaks verbatim.

This was on the other side of town—at the yellow apartment—before we’d made the hard switch to classic rock. Mike already had the orange one lined up, too, taking us straight through the Terror Alert color wheel. The joke was not lost on me, but I was serious when I told him I would quit before he found a red one.

Unfortunately, it was this yellow apartment that introduced us to the specter of death. Long before the Sniper started circling the city, Mike fell into a period of distraction. A new and brooding silence that coincided perfectly with the midpoint of his girlfriend’s pregnancy. We wouldn’t even turn the radio on some days.

It was one of these mornings when Mike climbed the roof with a bucket of yellow paint, only to find the top sealed shut. Painted on and baked hard in the sun. Mike tried to pop it off with a knife, but his foot slipped, and the blade jerked, right through his wrist.

“Fuck!” he yelled.

I stepped back to see what was happening, as the yellow paint came rolling off the roof and nearly struck me. WHAM! The metal can hit the ground and exploded all over my legs. Mike was already coming down the ladder, holding his wrist and cursing.

“What? What happened?”

He took his hand away and the blood squirted four feet across the sidewalk. Mike had severed one of the small blue power lines running up his wrist. Clutching it again, as he stared at me. “I cut myself,” he said simply.

“Jesus Christ. No shit,” I said, feeling completely scrambled. “What do we do?”

I walked away, looking for something, anything. I took my shirt off and pressed it to his arm. “Hold this,” I said, as we watched the dirty white cotton bloom with blood.

“Fuck, fuck.” I panicked. “Do we make a tourniquet?”

Mike just smiled dimly and walked away from me, toward his truck. I ran out ahead and opened the passenger side, helping him into the seat. I found the keys in his front pocket and slammed the door closed.

I wanted to call an ambulance, of course, but Mike wouldn’t let me. He said that he was fine; he’d insisted on driving, even. He was laughing when he said this to me. That was the thing—the anger was gone, and Mike was nothing if not tickled by the whole situation.

The pickup made a tortured sound and fired right up. With my adrenaline pumping, I found the clutch and scraped it into gear. We lurched forward and I felt insane. I didn’t know the first thing about driving a stick shift. I just tried to keep it in a low gear. Straight lines, I told myself as I accelerated into traffic. I was terrified of stalling this thing out. I couldn’t stop thinking of death. Was I really going to have to tell Mike’s girlfriend he was dead because I’d never learned how to drive a stick? I mean, Jesus Christ.

Mike leaned forward and flipped on the radio, inexplicably. Van Morrison’s “Wild Night” came blaring out of the tiny speakers. Mike smiled and started to sing.

“The wiii-iiii-iiii-iiii-iiiiiild night is calling! The wiii-iiii-iiiiiiii-iiiiiild night is calling!” He turned to me then, sounding insistent. “Sing it!”

“No.”

“Sing it, goddammit!”

“Shut the fuck up, Mike. I’m trying to drive!”

“Hurry!”

“I’m going as fast as I can!”

“I’m dying!” Mike screamed theatrically. “Aggghhhh! I’m fucking dying!” He was cackling and going delirious on me. I floored it through a red light, with horns screaming out on both sides. I couldn’t even hear myself think.

* * * *

In the end, of course, we made it. Mike lived. Everything was different after that, though. Mike became suddenly and unremittingly resolved. Resolved in being a father. Resolved in being alive. Resolved, even, in painting this next apartment orange. Slitting his wrist had been some kind of come-to-Jesus moment for Mike. The brooding silences were replaced by stupid jokes. NPR was overtaken by classic rock. He even entreated me to play the name game with him. Baiting me into talking him out of calling his unborn child Michael. One more thing that he was fully resolved about now.

“What about Tony?” I would ask mildly.

“Too ethnic,” he would deadpan.

“How about something modern, like Todd or Chad?”

“What is this, a country club?”

“How about Dave?”

“Too many vees.”

“It’s one vee,” I protested.

“That’s too many.”

And on and on this way. I couldn’t help but laugh with him. I’d started to wonder what kind of painkillers he was actually on. But mostly I resisted the urge to psychoanalyze Mike. I didn’t want to think about how the pressure he was feeling had caused him to cut his wrist and almost die. If he said that he was happy now, then I was happy for him. He could play the radio as loud as he wanted, for all I cared. I couldn’t even hear it anymore. Classic rock was the sound of orange paint drying.

* * * *

Slowly, I began to realize that my brother wasn’t leaving the house. Not to go back to Maryland, and not even to go outside. He wasn’t eating; he wasn’t showering. He hadn’t even changed his clothes yet. He carried around with him this undertow of dread. You could feel it coming off of him in waves as he stalked from room to room.

“Did you know that the Queen of England is in town?”

“What?” I asked. “Why would I know that?”

He shrugged. “She’s here to meet with the president. A state dinner or something.”

“Good. That will solve everything.”

He leaned against the counter and watched me put my groceries into the fridge. Staring at me, in silence. He was waiting for me to speak. He wanted me to tell him something now, I knew. But I didn’t even know what he was doing here.

“Here. Drink this. You’re freaking me out.”

I pulled a tall can off a six-pack ring and handed it to him. We leaned back against the countertop and drank our beers in silence. I was grateful for the car, of course, but at what cost? Was I really responsible for all of this? And what the hell was this anyway? I mean, how long were we actually going to do this?

“Did you go to school today?” “

No.”

“Why not?”

“You had my car.”

“You could’ve taken the subway.”

He didn’t answer. Sipping from his beer.

“What did you do all day?”

“I didn’t do anything. I watched TV.”

“Did you eat?”

“Not really.”

“Why not?” I asked, feeling exasperated. “What do you

do when you’re at school? Who cooks for you there?”

“Nobody cooks for me. There’s a dining hall.”

“You have a meal plan?”

“Yeah. I mean, of course.”

“Well, shit.” I beamed at him. “Why didn’t you say that two days ago? C’mon. Put your shoes on. Let’s go eat.”

* * * *

We drove the twenty minutes out to College Park; my brother in the passenger seat, with his shoulders tight around his neck. He used his ID card to swipe us into the dining hall, and there we were: a meal out on Mom and Dad. They would be pleased to know that we were finally spending some real quality time together.

The cafeteria itself was a veritable Valhalla of salts and sugars and fats. Decadent buffet tables lined with gleaming processed foods. These extraordinary foods that you would never actually pay for in a restaurant. Corn dogs and popcorn shrimp. Soft pretzels and shish kebabs. Mexican pizzas and English muffins. We ate potato skins and pigs in a blanket. There were chimichangas and Denver omelets. And we even ate some vegetables, too.

We stayed for nearly three hours, eating this way, in fits and starts. Feeling sickened and exhilarated in turns. We sat in silence, feeling full, feeling soothed. I watched the girls as they crossed the room, back and forth. These lively, pretty state school girls. This dining hall was teeming with blond and buxom cheerleaders. Former field hockey captains and high school prom queens. It was almost enough to make me give up on the orange apartment and go back to my own school.

“Where is your girlfriend?” my brother asked me out of nowhere. I looked up at him, baffled by the question. “The girl I met when—”

“I don’t have a girlfriend,” I said.

He stared at me blankly, before nodding. I looked away again.

“What about your roommate?”

“What?” Where were all these questions coming from? The kid barely says one word for three days, and now he won’t shut up.

“Your roommate,” he said again. “I haven’t seen him once since I’ve been there, and I’ve been there the whole time.”

“Okay?”

“So why hasn’t he come home?”

“I don’t know why. Sometimes he just doesn’t.” This was met with an anxious pause. “Why?” I smiled. “You think he’s been killed by the Sniper?”

“I never said he was killed by the Sniper. I just asked—”

“Why did they kick you out of school?” I interrupted.

“They didn’t kick me out of school. I told you, they kicked me out of the dorms.”

“What did you do?”

“I didn’t do anything.”

“Yeah, sure, whatever you say.”

I turned and tried to keep watching the girls, but my brother had ruined it. “Are you finished? Let’s go,” I said, picking up my tray and walking away from the table.

* * * *

Overnight, it seemed, the city had suddenly become a patchwork of blue and green tarps. Hanging loosely off of awnings. Covering doorways and entrances. Gas stations draped them over their corridors to obscure the innocent pumpers below. This was not diversion. This was an effort made, in earnest, to restore the public safety.

I could hear the cheap plastic rippling overhead as I filled Mike’s truck with gas. Staring at the rusted side panels, I tried to imagine the thing riddled with bullets. Mike liked to joke that the pickup never really rode the same after I drove it. There was a rumble, or a cough, somewhere deep down in the guts of the machine, he said. Buried a level below whatever I was hearing.

I looked up and watched a white van go wheeling through the intersection. This was strange, actually. I realized it was the first one I’d seen all day. What had happened to the others? I wondered. Was it possible that white vans were being rounded up and taken off the streets now? Registered? Detained? Disassembled?

I watched the people as they got out of their cars and circled the pumps. I watched their heads snap up as the tarps caught in the wind and shot out like sails. I watched the way they flinched when the nozzle clicked off in their hands. P-pop!

I saw a woman in black tights go scurrying across the street in a zigzag pattern. No one could decide who had told people to do this, but you would see it happening everywhere. The Metro Police were adamant about dismissing their own liability. They called it wanton superstition, and asked that people try to remain calm. But no one cared. It made sense to behave erratically now. I mean, what could it hurt?

Unfortunately, people were cracking up left and right. Something bad had happened that morning. One of our faithful disc jockeys had broken character and mentioned real life. I could hear it happening, too: this quaver in his voice as he started to speak. He was dedicating David Bowie’s “Heroes” to all the brave men and women of law enforcement.

“Ugh,” I said, getting down off my ladder, dejected. This man had broken through the fourth wall now, and there was no going back. This was not his job, of course. It was like watching a flight attendant start to lose it at thirty thousand feet. This was the moment we were all supposed to panic.

“Did that just really happen?” I asked.

Mike smiled and kept on painting. “Don’t worry. I’m sure he’ll be taken off the air for a few days.”

* * * *

My brother was already putting his shoes on when I walked through the door. With that fucking necktie hanging down in front of him, like a dog’s tongue. We didn’t even talk about it anymore. This was just our routine. We got into the Camry and drove out to College Park, where we ate our free meal together in silence.

Afterward, walking back out to the car, I gave him the keys. I told him I wanted him to drive now. I pointed out a liquor store with a burning yellow sign, and I told him to stop. My brother pulled the Camry into the parking lot and left it idling, with the doors locked, as I went inside. A minute later, I was back in the car, with a bottle of whiskey in a brown paper bag.

“Okay,” I told him. “Drive.”

“Where are we going?”

“We’re going to Michael’s,” I said.

“Michael who? The guy you work with? I thought you said he has a kid. It’s like ten thirty at night.”

“Don’t worry about his kid. Just drive the car.”

My brother sighed and put the Camry into gear.

“Turn up here,” I told him.

“Where?”

“Right here. Get onto the Beltway.”

He looked at me like I was crazy.

“Just do it.”

My brother shook his head and accelerated up the on-ramp and into the sea of red taillights on the westbound lane. Nobody had actually been killed driving on the Capital Beltway, of course. The Sniper waited till you stopped, till you stood still, till you looked the other way. But it was in the man’s name now; it was part of the stigma. And I watched as my brother’s grip grew tighter on the wheel.

I knew we weren’t far. There was a Home Depot in the suburbs where Mike and I would pick up paint. I could see it in my mind’s eye perfectly. Standing in the parking lot and staring across the buzzing traffic at this simple cursive sign.

“Okay, here. This is our exit.”

My brother sighed and turned off the Beltway. We were spit out onto an arterial road that funneled us down through an enclave of box stores and strip malls. The night sky was a wash of neon signs and corporate logos. We could’ve been anywhere in America right then. It was my brother who saw it first, though: the big glowing lights of a Michaels Craft Store. This bloodless hobby chain; the infamous setting of a half-dozen shootings in the spree.

“What the fuck?” my brother said.

“Turn.”

“No,” he answered as we passed the first entrance.

“What are you doing? I told you to turn!” We were coming up on the second driveway and he was shaking his head. “Park the fucking car!”

“No.”

I reached out and grabbed the steering wheel recklessly.

“Stop, stop! All right!” he yelled, and something snapped. As I let go of the wheel my brother made the turn into the craft store parking lot. He eased his foot off the pedal, letting the Camry coast.

“Just stop,” I said, and he did then. Turning off the engine.

We sat there in silence, staring out at nothing. I uncapped the whiskey and brought it to my mouth with a wince. “Drink this,” I said, pushing the bottle on him. But he wouldn’t take it. Leaning his elbow against the window, he looked angry enough to start crying.

“Jesus Christ,” he finally whimpered. “Why would you do this to me?”

“Will you relax? I told you to drink this.” And, after a minute, he did. Flinching with the first sip. My brother eased back against the headrest and stared out over the blank and empty lot. This was good, I thought. This was what I wanted.

“What are we doing here?”

“We’re being brothers.”

We sat there in the dark, with no reason and no plan. And in this moment my brother finally stopped asking why. He stopped expecting to get an answer out of me that would make any sense, at all, out of everything that was happening. And in this way the quiet here became infinite.

“Why did you get kicked out of the dorms?” I asked, for the one-thousandth time. But he didn’t answer. Taking a sip off the whiskey, he seemed to smile into the bottle.

“Do you trust me?” I asked him.

“What?”

“Are you afraid?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Does this feel like your home?”

“In what way?”

“Do you believe in God?”

“What?” he said, losing patience.

“Have you ever been in love?”

“Fuck you,” he scowled.

“Have you ever even had sex?”

There was a long pause here as he opened his mouth to answer me. But he looked away instead. What did that mean?

“I’m going to keep this car, you know.”

He didn’t answer.

“Are you listening to me? It’s mine now. No sense in being mad about it.”

When he didn’t answer again, I took his necktie in my hand. Turning it over gently. “And take off this fucking tie!” I said, ripping down on it.

My brother came uncoiled in an instant. Shoving my head against the window, hard. I laughed and smiled at him with wet lips as he seethed at me. We sat there, the two of us, trapped in this car. In this parking lot. In this suburb. In a war zone. This had been my idea all along, I supposed.

“I love you,” I said, with a sickening smile. “Do you love me?”

He clenched his jaw, not answering.

“I’m your older brother,” I barked at him. “You’re supposed to worship me the way that Jeb worships George.”

“Jeb hates George!”

“Everybody fucking hates George, asshole! You’re my brother.”

“Fuck you.”

There was a long silence again before I took the bottle away from him.

“Why did you get kicked out of the dorms?” I asked.

“I didn’t,” he said.

“What?”

“I just left.” He stared out the windshield, toward the entrance of the Michaels Craft Store, and he started to smile.

I didn’t even know what to say to this. I could feel my face begin to burn. I was furious at him for this stupid lie. I was ready to start screaming in his face.

But before I could even get my head around, there was a rap against the glass. My brother and I jumped. This was followed, in short order, by the blinding beam of a flashlight, and a brawny command to roll down the window. My brother did this and we found ourselves squinting into the face of a young police officer. He banked his flashlight around the inside of the Camry, blinding us once again. We stared back at him, waiting. The young cop’s face was grim. Nervous. We seemed to catch him in a moment of indecision. He couldn’t have been more than twenty-five years old.

I moved the whiskey bottle against the door, knowing full well that the cop had already seen it. But he didn’t say a word. We stared straight ahead as he walked around the back of the car, peering through the windows. He studied my brother’s boxes in the backseat. I was sure it must’ve looked like we were living in this vehicle.

“You shouldn’t be out here,” he said, flicking off the flashlight. “This is a dangerous place.”

We nodded dumbly. We could hear the tension in his voice now. The frayed edges of a man who’s been drinking coffee to stay awake.

“You don’t wanna end up in the newspapers. Believe me,” he said. “You don’t wanna make yourselves a part of this thing.”

He raised his head to look behind him, into the street. Watching an eighteen-wheeler blow by in a flash. The Sniper had yet to pick off a police officer, we knew, but it was hardly out of the question. He turned back to us with a big moony face.

“Where are you boys from?”

“We’re from here.”

“Not me,” my brother spoke up stupidly.

“Uh-huh,” the young cop said. “That’s how come the New York plates?”

“Right, yes. This is my brother. He drove this car down from Buffalo. He’s leaving it for me. It’s mine.”

My brother didn’t say a word.

“Uh-huh,” the young cop said again. He didn’t seem to know what he was doing out here, I thought. Alone and in the dark. He didn’t even ask for our IDs. He just anchored himself there. Holding on to the side of the Camry, as though the whole thing might float away.

“This is some shit,” he said absently.

My brother and I nodded, letting him talk. But he stopped again. We waited for him to bust us now, to end all of this, but he didn’t. Was this really the guy meant to find and kill the world-famous Sniper? Or, worse, to apprehend him peaceably? How the hell was that going to work? You could practically read the question on his face.

In a blink, the darkness was punctured by a flash at the far end of the lot. The young cop jerked up and pulled away from the Camry. We saw a pair of headlights dip and bob, as they bounced over a speed bump a hundred feet away. The driver slowed down suddenly as he picked out the police cruiser in the shadows.

The young cop reared up, with a hand on his gun belt, as the vehicle began to veer off in a slow, sweeping turn. And, all at once, it was there: a white van!

“Stop!” the young cop shouted, following this vehicle into the distance. “Stop!” he yelled again, as he ventured out into no-man’s-land. My brother didn’t hesitate. He turned the key in the ignition, and the Camry fired back up.

“What are you doing?” I asked in a panic.

The cop turned, too, holding out his pistol in a disoriented way. He took his eyes off the van as we pulled away in a rush. The young officer was going to have to shoot out our tires if he wanted to stop us now. I gripped the armrest as my brother floored it through a yellow light and back up the on-ramp. I turned and looked over my shoulder and saw the young cop running into the darkness again. Still chasing the white van.

* * * *

In the morning, my brother was gone. He had taken the Camry with him, of course. I knew this even before I went outside to look. He was on his way back to my parents’ house. This had been his plan all along.

I shouldered my bicycle back down the stairs to the street. Exhaling before I swung my leg over the top bar. I could already feel the heat coming up off the blacktop. Mid-October, and the humidity still hadn’t broken. I was miserable; I was hungover; I was aggrieved. I didn’t want to do this anymore.

Mike just nodded and climbed up his ladder when I told him I was quitting. I couldn’t care less, honestly. Let him be pissed off all he wanted. Let my brother be pissed off, too, for all I cared. That motherfucker stole my car.

It was time for me to go back to school now anyway, to get on with it. This was supposed to be my senior year in college, for fuck’s sake. Mike and I both knew that he was perfectly capable of finishing the orange apartment by himself.

At lunchtime, we got into the truck and drove down Georgia Avenue in silence. We were headed downtown to a hardware store where Mike kept a standing account. We made our turn, and cut across the avenues, where we found ourselves suddenly, and unaccountably, stopped. Traffic had come to a dead halt at Fourteenth Street.

“Holy shit,” Mike said softly, and I felt my stomach drop.

I knew immediately that I did not want to see this. But when Mike opened his door, I followed him. Everyone was leaving their vehicles now, as the sidewalks filled with people. I walked behind them, feeling anxious. Feeling vulnerable.

There were two motorcycle cops holding traffic in the street as people lined up on the sidewalks, standing shoulderto-shoulder. Mike and I moved through the crowd, stepping down off the curb, where we were confronted, inexplicably, by nothing. We looked across to the other side, where people craned their necks the same way. Looking dumbfounded; looking disappointed. There had been no shooting after all. No white van. No bodies lying bloodied in the street. There wasn’t even a car crash to gawk at.

“What’s going on?” Mike asked one of the motorcycle cops.

“Queen of England is coming through,” the cop said flatly.

“The Queen of England?” Mike asked indignantly. The words didn’t seem to fit in his mouth. Mike turned away and looked at the gathered crowd.

“We have to get through here. You’re blocking us in.”

“Everybody has to wait,” the cop answered.

“The Queen of England,” Mike said again with disgust. “Look at all these people on the street! You’re putting all these people in danger! You realize that, don’t you?” But the cop wasn’t listening.

The crowd began to titter as the Queen’s cavalcade breached the hill. This opulent and imposing show of force; a motorcade running more than a dozen vehicles deep. Motorcycles and police cars and unmarked SUVs formed a pocket of protection around Her Royal Highness. Look at all of these resources on display, I thought. Imagine all of this Sturm und Drang for a doddering old woman. The Queen of England, no less!

But Mike began to boo. Pushing up to the front and booing lustily at the passing cars. “Boooooooooo!” Mike bellowed through his dirty hands. “Boooooooooo!” He was a single voice cutting through the din of our collective bewilderment.

I didn’t know what to make of this. The veins were bulging in his neck as he shook his arms and taunted. I was afraid I was going to have to pull him out of the street now. But, almost as suddenly, people started joining in; picking up Mike’s war cry as a chant. This big and brawling noise that started somewhere in their guts. A raucous and spontaneous protest that was suddenly irresistible. People were booing the Queen!

I pushed up to the front, next to Mike, where I could see her limo rocketing past. “Boooooooooo!” I screamed, feeling giddy and alive. To know for a fact that the Queen of England was hearing my voice was a strange thrill. I was smiling like crazy as I heckled with the crowd. Ours was a deep and guttural complaint. It was a thing beyond reason or reproof. I had chills running up my spine.

The whole thing was over before it started, though. The motorcade flashed in the sun and the roar died out. The crowd began to laugh. Where had all of this come from anyway? People felt the urge to look away, to disavow themselves from the noise that they had made. These were not the kinds of people who felt a frenzy in their anger. These were not the good folks who identified with a mob.

I watched as the motorcycle cops who had barred our passage fell into line behind the Queen, and the show was over. People scattered and cars were set in motion. The sidewalks cleared, and it was almost as though it had never happened. And, for all the good it might’ve done, it hadn’t, of course. But what did that have to do with us?

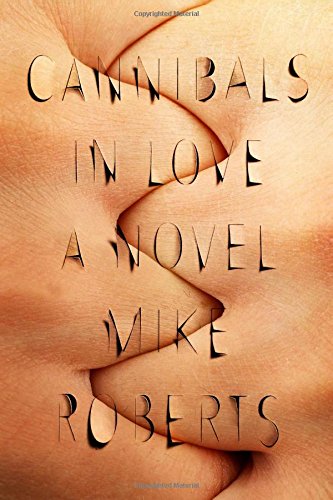

From CANNIBALS IN LOVE. Used with permission of FSG Originals. Copyright © 2016 by Mike Roberts.