A Night with Virginia Woolf at America's Strangest Literary Hotel

A Room of One's Own, In View of a Lighthouse

My friend Devika taught me that if you stop for a burger on your way home from a trip, you’ll significantly mitigate your post-vacation blues. It’s important to not go directly home. It’s important to delay the cruddy feeling of unpacking, of finding the dirty dishes you left in the sink.

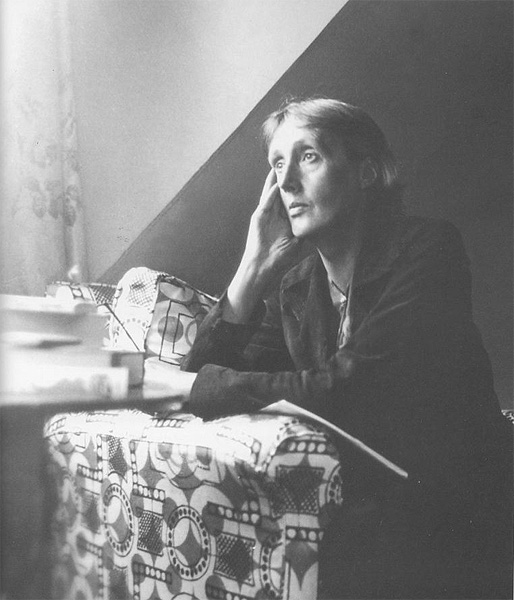

Virginia Woolf probably didn’t eat burgers, but she did like to leave London when she got the chance. In 1940, she went, as she did most summers, to Monk’s House, the cottage in East Sussex where she and husband Leonard like to hang out, write, and, I don’t know, take naps. But that year, the trip offered no respite. Woolf’s diary entries from the time are teeming with dread.

“L. says he has petrol in the garage for suicide shd. Hitler win,” she wrote in May. While the world seemed to be ending, Woolf was trying to finish what would become her final novel, Between the Acts. In August, she wrote the seminal essay “Thoughts of Peace in an Air Raid,” which delineates the terror she felt in bed at night, listening to German planes overhead.

Virginia Woolf at Monk’s House

Virginia Woolf at Monk’s House

But that summer wasn’t entirely wretched; she appreciated “lapses in anxiety” and moments of joy. In June she wrote in her diary that in such a time, “[o]ne taps any source of comfort” one can. I picture her finding comfort in short walks. Or lying on the floor. Maybe with a snack.

*

I brought really excellent snacks with me to the Sylvia Beach Hotel: almond butter and donuts and gummy candy. I also brought a toothbrush. I brought Rachel Khong’s excellent Goodbye, Vitamin. I brought Doc Martens and a jacket for beach walks.

The Sylvia Beach Hotel is not on some beach named Sylvia, but on a cliff overlooking Nye Beach in Newport, Oregon. And anyway, Sylvia Beach was not a beach but a woman. She is best remembered for founding and running Shakespeare and Company, the Paris bookstore where Gertrude Stein and her clique used to hang out in the 1920s and 30s. In 1921, Beach published the first edition of Joyce’s Ulysses when no one else would. This eventually bankrupted her—Joyce published the second edition with another publisher and left her in debt.

The Sylvia Beach Hotel as seen from Nye Beach. Photo by Claire Luchette.

The Sylvia Beach Hotel as seen from Nye Beach. Photo by Claire Luchette.

During World War II, Beach kept Shakespeare and Co. open, even after Paris fell in 1940; she was forced to close by the end of 1941. Ultimately, Beach was captured and interned for six months at Vittel. Upon her release, she did not reopen the store. George Whitman is credited with opening the modern-day Shakespeare and Co., which he renamed in tribute to Sylvia’s store on the 400-year anniversary of the Bard’s birth in 1964.

Oregon’s Sylvia Beach hotel opened in 1987 on what would have been Beach’s 100th birthday. Much of the décor hasn’t been changed since. In the 80s, the owners, Goody Cable and Sally Ford, asked family and friends to sponsor rooms—sponsors would pick their favorite authors, pay to decorate the room, and they’d get a free weeklong stay every year. Perhaps relatedly, the rooms inspired by male authors seemed to be more lavishly decorated. Jules Verne’s room is modeled like a submarine, the Oscar Wilde room has a single bed and is decorated in green florals. Some nerd chose Lincoln Steffens as his or her favorite author; that room’s got a typewriter.

Before I made the trip, I had a brief moment of horror when I learned on the website I would need to call in order to reserve a room. I hate talking on the phone; I’d rather vacuum my ceiling or swallow a sandal. But I took a deep breath and dialed. The staff was helpful, informative, upbeat. Not too unlike Sylvia Beach herself, as the New York Times described her in 1922: “ready to welcome visitors on almost any morning or afternoon.”

Photo by Claire Luchette.

Photo by Claire Luchette.

I asked for the Virginia Woolf room. I was told there’d be a cat and no Wi-Fi. I am allergic to cats and addicted to the internet, but I figured some time without a screen could do me good. The website promised I would have the chance to “[u]nplug, unwind, and sleep with [my] favorite author.” No, no, no. “I do not want to sleep with Virginia Woolf,” I thought on my drive to the hotel. I imagine she was a fitful sleeper. She probably had sleep apnea. Also, she’s dead. Dead people, by and large, make poor bedfellows.

The Woolf room is on the first floor of the hotel. When unoccupied, rooms are left open, so I had the chance to poke around.

Only two of the hotel’s 21 rooms are dedicated to writers of color: the Amy Tan room and the Alice Walker room. In the Alice Walker room, there’s a mural that seems to indicate that no one connected to the hotel has ever read The Color Purple or “Everyday Use” or taken the time to ask a bookseller about Alice Walker.

Photo via the Sylvia Beach Hotel.

Photo via the Sylvia Beach Hotel.

Note the zebra blanket.

When I asked a staff member about the mural, she said it had been painted back when the hotel first opened.

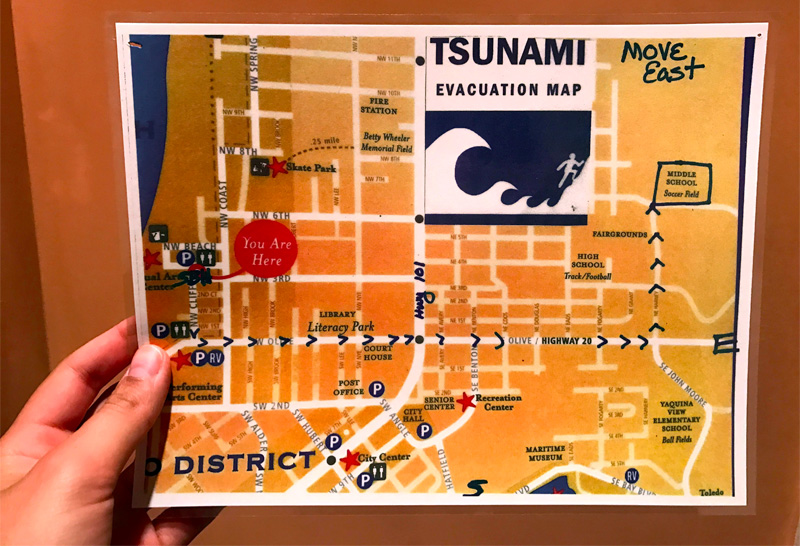

After, I took a walk along the beach to clear my head. I can’t say this exactly worked. The Pacific Ocean is a fickle friend. It’s gorgeous, yes, and I could happily subsist on oysters and fish sticks alone. But when I looked at those waves, I thought only of impending doom: The Really Big One. Those houses on the beach, I thought, are going to be toast.

It’s as if the hotel could read my mind: a Tsunami Evacuation map was posted on my bathroom door, with big arrows pointing east, away from the beach.

Photo by Claire Luchette.

Photo by Claire Luchette.

Woolf would have welcomed a tsunami, probably, had one hit London while she was there, preferring natural destruction to death by fascism.

*

Included with my stay at the hotel was self-serve spiced wine at 10 pm and communal breakfast anytime before 10 am. I am not very enthusiastic about breakfast, and less enthusiastic about eating breakfast with people I don’t know. But I tried it for the sake of journalistic integrity. Also for the free coffee.

I claimed half a grapefruit and sat down at an empty table with an ocean view. An old man named Joshua asked to join me. He wore bright green suspenders and was staying in the Oscar Wilde room. Here are some things Joshua told me, unsolicited: one of his dearest friends is a belly dancer; most books that are published are absolute crap; really he only reads science fiction; I should start saving for retirement; he had just bought a great house.

“Uh huh,” I said. I wanted to quote Woolf at him: “What was the use of talking, talking?”

Eventually Joshua bid me adieu—literally said “I bid you adieu”—and I took my coffee up to the hotel’s library, a beautiful space in the eaves. Cushy chairs; a treasure trove of ancient books, puzzles, and board games; a little deck that looks out on the waves. I read Goodbye, Vitamin and laughed audibly. I did not miss my Wi-Fi.

*

“Woolf would have hated the Woolf room,” a friend told me when I described the décor: rich purples and pinks, a garish dresser, every variety of floral print. A pillow decorated with puff paint. And Virginia’s face everywhere. Wouldn’t she have a framed photo of Leonard or Vita or Vanessa? My friend is right: the room would have given Woolf one of the mighty migraines for which she was known.

Photo by Claire Luchette.

Photo by Claire Luchette.

But a few miles down the beach from the hotel is the Yaquina Head Lighthouse. At night, I drank the free spiced wine from a mug and watched the light sweep across the ocean. Silent, dignified, steady. In these moments, I thought—duh—of Woolf, and the Ramsays’ long struggle, in To the Lighthouse, to get to the lighthouse. Of the novel’s final scene: Lily Briscoe at her canvas, all tuckered out. There, in the hotel’s attic, was the Woolf-y feeling I’d come looking for: isolation, but also the reminder that my solitude was in no way singular.

When it came time to check out of the Sylvia Beach Hotel, I followed Devika’s advice about trips: I did not go directly home. I drove to the lighthouse, paid to park. The lighthouse was being restored—there was a fat blue crane parked in front of it—so I couldn’t walk up to it. Instead, I walked through the parking lot and looked out at the rocky beach. I thought not about destruction, about earthquakes and tsunamis and war, but about creating. I thought of the last line Woolf wrote in her diary, three days before she died in March of 1941, from Monks House: “L. is doing the rhododendrons . . . ”

The Yaquina Head Lighthouse. Photo by Claire Luchette.

The Yaquina Head Lighthouse. Photo by Claire Luchette.

That’s the image that lasts, when I think of the Woolfs at wartime. Not dread, not fear. Leonard in the garden, working with the flowers, hoping what he had grown would look the best it could. And Virginia, having recently finished a draft of her last novel Between the Acts, thinking of him, safe for a moment inside the house.

Claire Luchette

Claire Luchette is a writer from Chicago. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Ploughshares, Indiana Review, Glimmer Train, and O, the Oprah Magazine.