A Brief Literary History of Birth Control

From George Orwell and John Updike to Grace Metalious and Alice Munro

The history of out-of-wedlock pregnancies in literature is a rich one. Without it, Nathaniel Hawthorne couldn’t have written The Scarlet Letter, nor could Theodore Dreiser have created An American Tragedy; in Howards End, E.M. Forster used it not to undo individuals but to indict an entire society. Then in the 1920s, along came Margaret Sanger and her crusade to make birth control legal and widely available. Suddenly, it was harder to get a girl in trouble. But therein lay a new inspiration. The choice to use contraception (or not) can reveal character, drive action, and hijack plot.

George Orwell, Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936)

Not everyone regarded birth control as a boon. In Keep the Aspidistra Flying, George Orwell puts a screed against contraception in his protagonist’s mouth. On the verge of having sex, Rosemary stops because her lover Gordon refuses to use a condom. “This birth control business!” he lectures her, “it’s just another way they [capitalists] have found out of bullying us.” He goes on to speak about the “estranging shield,” a phrase Orwell takes from his poem “St. Andrew’s Day, 1935,” which some critics suggest is the first reference to a condom in English poetry.

Flannery O’Connor, “A Stroke of Good Fortune” (1949)

In Flannery O’Connor’s short story “A Stroke of Good Fortune,” the pregnancy is not illegitimate, but it is undesired. The narrator Ruby, who watched her mother wither and die from too many children, never mentions the form of birth control she—or rather, her husband Bill Hill uses—but she clearly relies on it. Refusing to admit the possibility of (or even mention the word) pregnancy, she whistles desperately in the dark. “Not me! Oh, no, not me! Bill Hill takes care of that . . . Bill Hill’s been taking care of that for five years!”

Grace Metalious, Peyton Place (1957)

In Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place—which scandalized the nation, exasperated critics, and sat on the best-seller list for more than a year—sex (and a great deal of it) results in illegitimate birth, abortion, and other consequences considered socially unacceptable at the time. But Betty Anderson, the town bad girl who works in the local mill, is the only one concerned with contraception, undoubtedly a sign of her loose morals. After a steamy interlude on the beach, she turns on the mill owner’s son for being less experienced than he’d pretended. He hadn’t even known enough to “wear a safe.” Five weeks later, Betty is pregnant.

Philip Roth, Goodbye Columbus (1959)

Brenda Patimkim, the spoiled, conflicted rebel in Goodbye Columbus, gets a diaphragm at the urging of her lover, Neil Klugman. Brenda’s experience is, at first, a lark. When she comes out of the doctor’s office to the square across from Bergdorf Goodman where Neil is waiting and he asks where it is, she tells him she’s wearing it. But when Brenda returns to Radcliffe in the fall, she leaves the diaphragm in a drawer for her mother to find, thus sabotaging the affair.

John Updike, Rabbit, Run (1960)

Rabbit Angstrom of John Updike’s Rabbit, Run, has an aversion to contraception, but unlike Orwell’s character, he objects to it on physical and aesthetic rather than political grounds. When Ruth Leonard, the “hooer” to whom he’s giving fifteen dollars “toward [her] rent,” is about to slip into the bathroom to insert what he calls a “flying saucer,” he stops her with the argument that he’s “very sensitive.” “Do you have the answer then?” she asks. “No, I hate them even worse…If you’re going to put a lot of gadgets in this,” Rabbit, who has abandoned his pregnant wife and child, goes on, “give me the fifteen back.”

Mary McCarthy, The Group (1963)

Perhaps the most humiliating scene ever written about birth control occurs early in The Group by Mary McCarthy. Dottie Renfrew, a recent Vassar graduate who has just lost her virginity to a man she barely knows, takes his advice and gets a diaphragm from a doctor modeled on Hannah Stone (who became medical director of Sanger’s Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau of New York in 1923). Despite some initial embarrassment, the medical visit is a success; afterward, however, Dottie spends the day waiting for her lover in New York’s Washington Square Park. When night falls and he still hasn’t turned up, she leaves the package containing the new device, along with her romantic illusions, under a bench and goes home to Boston.

Edna O’Brien, Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964)

Kate and Baba, the protagonists of the third novel in the Country Girls trilogy by Edna O’Brien, know about contraception, but they can’t get their hands on it in fiercely Catholic Ireland, where the book was initially banned. In fact, birth control is so out of reach that it isn’t mentioned until this final novel set in London—and then only obliquely and in lament for its absence. Baba reports that the man she will end up marrying is, “Bad in bed. But . . . It made him a hell of a sight nicer than most of the sharks I’d been out with who . . . wanted some new, experimental kind of sex and no worries from you about might have a baby, because they liked it natural, without gear.” Later, a distinctly kinky lover pleads with her, after the fact, to promise him she won’t get pregnant. “He was an imbecile. On second thoughts I was the imbecile. I suppose he thought with the tights and the elaborate bathrooms I knew all there was to know.”

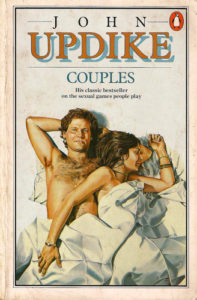

John Updike, Couples (1968)

Eight years after the publication of Rabbit, Run, Updike not only espoused birth control but also identified it by brand name. The first time Piet and Georgene, married to other people, have sex, he worries about “making a little baby,” and she’s surprised he doesn’t know about Enovid. “Welcome to the post-pill paradise,” she tells him, and the “light-hearted blasphemy . . . immensely relieved him.”

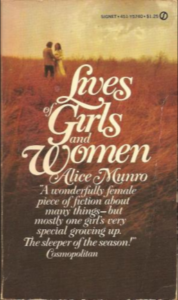

Alice Munro, Lives of Girls and Women (1971)

In Alice Munro’s novel about a young girl coming of age in in rural Ontario in the 1940s, the protagonist Del Jordan’s mother warns her that if she lets herself get distracted by a man, her life will never be her own. “You will get the burden, a woman always does.” Del replies glibly that “there is birth control nowadays” and rejects her mother’s message that “being female made you damageable.” She resolves to live like men who are “supposed to be able to go out and take on all kinds of experiences and shuck off what they didn’t want and come back proud.”

Ellen Feldman

Ellen Feldman, a 2009 Guggenheim fellow, is the author of Paris Never Leaves You, Terrible Virtue, The Unwitting, Next to Love, Scottsboro (shortlisted for the Orange Prize), The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank (translated into nine languages), and Lucy. Her novel, Terrible Virtue, was optioned by Black Bicycle for a feature film. The Living and the Lost is her latest novel.