10 Works of Literary Horror You Should Read

(Even if You Don't Think You Like Horror)

This week, Victor LaValle’s new novel The Changeling hits shelves. This is only the most recent installment in a long series of great works of literary horror, and as a reader of primarily literary fiction, but with a major soft spot for, as they say, “genre,” its release has me thinking about horror and high-brow literary fiction and the ways in which they intersect.

Like all genres, literary fiction included, horror is a watery one. What makes something horror? What makes something literary? No one can say exactly. The term “horror,” in general, denotes a sense of fear and disgust, so I would argue that any work of literature written at least partly in order to elicit one or both of these feelings in the reader would qualify. As for “literary”? I’d venture to argue that for something to be literary it has to have a certain elevation of prose, a sense of the sentence level as opposed to simply subject matter or plot. (There are plenty of those who say that it’s characterization that makes something literary, but I’ve read too many experimental novels to believe it.) But what does that mean, exactly? I don’t know! Like porn, you know it when you see it. I see here that I’m comparing literary fiction to porn, and I feel good about it.

I suppose my idea of literary horror is similar to the “suggestive horror” that Brian Evenson discusses during an interview at The White Review: “The notion of a more suggestive horror, which raises the spectre of an insidiously elusive reality, is much more frightening than a lot of what gets called horror, and more realistic than what gets called realism.” That is, while blood and guts and the literary equivalent of jump-scares are not excluded here, the aim is for something that goes a little deeper than that. Below are ten such books—ten of many, of course, on a list that leans towards my own interests and taste, so feel free to add on—or continue the argument about Beloved—in the comments.

Victor LaValle, The Changeling

I heard LaValle read from The Changeling in 2014 at the University of Virginia, possibly the worst year in (recent) memory for the community. His reading took place after the disappearance and murder of a second-year student but before the infamous Rolling Stone article. It was for that reason that he gave us a trigger warning before he began, something he said he didn’t usually do. In this case, I was happy to have had the chance to steel myself—this book is scary. The section he read—in which the protagonist, Apollo, is U-locked to a steam pipe listening to the scream of a tea kettle, fearing for his son’s life—had the entire room riveted, sweating, and desperate to buy the novel. Now we all can.

Brian Evenson, Last Days

Or really anything by Brian Evenson, who is one of the first names that springs to mind whenever I think of literary horror. A writer who famously broke with the Mormon church over his writing, Evenson’s work pulls from many genres—he’s also a translator of French literature, and as B.K. Evenson, science fiction—but a better writer of gruesome philosophy there might not be. Last Days, which won the American Library Association’s award for Best Horror Novel of 2009, is a detective novel and a cult novel (in that it is about cults—though perhaps the other designation would work too) and a brutal horror novel and a fine work of minimalist literary fiction.

Toni Morrison, Beloved

Beloved is one of the most frightening books I’ve ever read. Not because anything jumps out at you (though there is a haunted house), but from the psychological horror that runs as an undercurrent throughout, from those first lines: “124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom.” The fact that the novel is based on the story of a real woman makes it rather worse.

This book is interesting genetically—it’s a ghost story, and a scary one, but it’s also unimpeachably literary. Obviously, I don’t think these two things are mutually exclusive. But in this case, as Grady Hendrix pointed out at Tor not too long ago, it’s the horror community that doesn’t seem to want to claim Beloved. On the one hand, of course it isn’t a conventional horror novel. On the other: hey, look at that vengeful ghost, and also, well, there’s that feeling of horror you get when you read it. After all, it’s about a woman dealing with the fallout from murdering her own child—Sethe is, as Hendrix put it, “that most feared and despised figure in Western Civilization, the murdering mother”—to save her from the greater nightmare of slavery. In the sense that “horror” as a genre is most essentially defined as “that which creates a sense of fear and disgust in the reader,” I think it counts.

Ryu Murakami, Piercing

No ghouls or monsters or stalking spirits in this one—unless you count the utterly horrifying Kawashima Masayuki, who is really all three of these, and worse. I like to call Ryu Murakami “the other Murakami”—where Haruki Murakami is absurd and cat-covered, with magical ears and mournful handjobs aplenty, Ryu Murakami is dark and cold-blooded, though sometimes equally antic and fantastical. In this novel, Kawashima is afraid that he’s going to stab his infant daughter—he just can’t help himself—and so he hires a prostitute and plots to stab her instead. Things go awry. I read the whole book with my shoulders pressing into my ears, if that tells you anything.

Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

As much as I want to talk about We Have Always Lived in the Castle, my favorite Jackson work, and probably (since you asked) in my top ten short novels of all time, The Haunting of Hill House is a more definitive work of horror for one of the queens of the genre (after all, her namesake annual award is given “for outstanding achievement in the literature of psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic”). The Haunting of Hill House is kind of the ur-haunted house story, in which four people in a creaky old mansion begin to experience strange things—and then stranger things. It’s a good introduction into horror because there isn’t much in the way of blood and guts, but more of a creeping, cursed, torturing feeling that seizes both characters and reader by book’s end.

Paul Tremblay, A Head Full of Ghosts

This gripping, somewhat postmodern horror novel asks the hard questions—the most urgent being “schizophrenia or possession?” Fourteen-year-old Marjorie seems to be suffering from the former, but when a priest and a reality television show come into the picture, things get rather more complicated. It’s a novel about memory, perception, and the terror of not-knowing. As Tremblay put it in an interview about the novel at io9, “Ambiguity is our permanent state, isn’t it? We don’t like it being so. Most of us crave order and routine, and yet yawning before us is our future, as frightening as it is thrilling. . . . [T]he idea that our reality or present is murky and malleable is unsettling, and it’s unsettling because it’s the truth. Horror lives in those liminal or in between spaces, the cracks of things. The closer a horror story gets to the truth of things, the more affective it is going to be.” Sounds just like what we say about literary fiction, doesn’t it?

Stephen Graham Jones, After the People Lights Have Gone Off

Jones is another prolific writer of literary horror, so many of his books could fit onto this list, but his most recent story collection wins its place from its title, which I find deeply scary without being able to put my finger on exactly why (maybe it’s just the very horrifying images from the story to which it refers—but I think even without that context it’s creepy). These stories inject the everyday with terror while playing with the conventions of both the literary and horror genres.

Sebastià Alzamora, Blood Crime (trans. Maruxa Relaño and Martha Tennent)

Seeing as this is a vampire novel set during the Spanish Civil War, there’s more than one kind of horror at hand—but the vampire, after an eloquent and exuberant entrance, soon takes a backseat to the more human horrors of war. Alzamora is a poet as well as a novelist, and has created a thoroughly modern horror novel here.

John Ajvide Lindqvist, Let the Right One In (trans. Ebba Segerberg)

A chilling novel—both literally and figuratively—about a bullied young boy who finds a strange friend. Very strange. Yes, a vampire, but more than that: a soulmate. The book is cerebral and melancholic, violent and oppressive, and well worth reading even if you have seen the film (or both films).

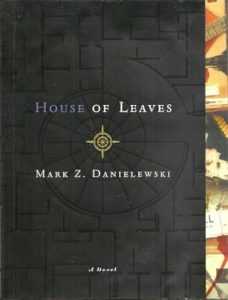

Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

For me, the jury’s still out on whether this is really a horror novel—but enough people think it is, and enough people who wouldn’t normally read horror love it, that I’m including it here. It is nominally about a kind of haunted house—one that’s bigger on the inside than it is on the outside, and also drives people insane—but of course the most interesting thing about it is the labyrinthine format, mirroring, and post-modern textual devices. To me, the most compelling argument for House of Leaves as a horror novel is the way it makes you, as the reader, feel claustrophobic and unmoored along with the characters. It certainly evokes something, anyway.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.