10 Transgressive Fairy Tales for Grown-Ups

If Only Disney Would Remake These

They may be ancient forms of storytelling, but fairy tales are still big business. Case in point: the new Disney live-action version of Beauty and the Beast—which was not the least bit artistically necessary, by the way, considering that the original is Disney’s best film of all time—just opened to the catchy tune of $170 million in ticket sales, setting a new record for March opening weekend sales. (So I suppose “artistically necessary” isn’t exactly what’s driving decisions here.) At any rate, the revival of Beauty and the Beast, and all the attendant hand-wringing over Emma Watson’s feminism, has gotten me thinking about actually transgressive, interesting, and yes, maybe even feminist retellings of fairy tales. There have been hundreds of these over the years, but here are a few of the most interesting—in this writer’s opinion, of course—from reinterpretations to new myths, from classic to current. Sure, go see Beauty and the Beast, but for my money, I think Angela Carter will show you a better, bloodier time.

Virginia Woolf, Orlando

Woolf’s love letter to Vita Sackville-West is also a fairy tale—what else to call a novel in which Orlando wakes at the stroke of midnight, after a long magical sleep, having been transformed from man to woman? Allusions to Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella abound in this novel, but even more convincing is the playfulness of Woolf’s prose, the plainly put plot points (“It is enough for us to state the simple fact; Orlando was a man till the age of thirty; when he became a woman and has remained so ever since.”). No doubt it is one of the greatest novels to make use of the four formal elements of the fairy tale as explained by Kate Bernheimer: flatness, abstraction, intuitive logic, and normalized magic.

Helen Oyeyemi, Boy, Snow, Bird

Oyeyemi is a fairy-teller of many forms, and her meta, magical Mr. Fox would also suit this list well. But Boy, Snow, Bird is even more interesting in some ways, a total transfiguration of the Snow White story set in the 1950s, in which a woman, Boy, runs away from a horrible father, marries a handsome widower, is envious of his beautiful daughter—and then has her own, whose dark skin reveals a secret about her husband. But it’s not only the strange alchemy of “passing” that Oyeyemi is examining here. “I wanted to rescue the wicked stepmother,” she has said. “I felt that, especially in Snow White, I think that the evil queen finds it sort of a hassle to be such a villain. It seems a bit much for her, and so I kind of wanted to lift that load a little bit.” Rescuing the wicked stepmother is a transgressive act indeed.

Jeanette Winterson, The Passion

As in Orlando, there is much challenging of traditional forms (this is apparently a historical novel), as well as gender norms and possibilities here, not the least of which have to do with the gender-fluid, bisexual, web-footed Villanelle, and who falls in love with a woman she calls the Queen of Spades—a woman who captures her literal heart. Add to all this Henri, who is driven mad by his love for Villanelle, who cannot love him back—even after he steals back her heart. Everything a fairy tale should be, in my opinion.

Donald Barthelme, Snow White

Another take on the Snow White story, this one much weirder and raunchier than Oyeyemi’s. In this formally bizarre and disjointed narrative—I mean, there is a quiz on page 88 with questions like “Does Snow White resemble the Snow White you remember? Yes ( ) No ( )” and “Have you understood, in reading to this point, that Paul is the prince-figure? Yes ( ) No ( )” “Do you feel that the creation of new modes of hysteria is a viable undertaking for the artist of today? Yes ( ) No ( )”, which is its own kind of magic, really—Snow White lives with Kevin, Edward, Hubert, Henry, Bill, Clem, and Dan, who make Chinese baby food and wash buildings and gawk at women. And…I really can’t tell you anything else that happens, except that it’s all bonkers-thrilling, an ecstasy of the disturbing and absurd.

Anne Rice, The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty

Erotica, particularly sadomasochistic erotica, is often transgressive, and this novel—which makes 50 Shades of Grey seem like a kids’ book—is a fine, horrifying example. To be fair, the beginning of this book, in which the Prince comes upon Sleeping Beauty and wakes her up by having sex with her, is much closer to the original—in which he rapes her in her sleep, but she doesn’t wake up until later—than the version we’ve all been fed (chaste, closed-mouth kiss, voila, Happily Ever After). But this retelling is more than a simple sexual exaggeration of the powerful man/submissive woman narrative of the original tale—all genders have the opportunity to be submissive in Rice’s world…

Franz Kafka, The Complete Stories of Franz Kafka

Kafka didn’t write fairy tales, you say? Well, of course not. In fact, he has been described by fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes as the creator of the “anti-fairy-tale,” which is a different kind of transgression that some of the others we’ve seen here. As Patrick Bridgwater put it in Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale, “The folk fairytale depicts an ordered world, Kafka a disordered one. He uses the style, structure and motifs of the folk fairytale to deny the positive aspect or ultimate meaning of the genre. Its negative aspect, on the other hand, is present in his work, in which arrogance and greed are punished.” When you become a speechless creature and your family goes on to live happily without you, that’s some strangeness indeed.

Yumiko Kurahashi, trans. Atsuko Sakaki, The Woman with the Flying Head and Other Stories

An amazing, surreal collection of sexually-charged fairy tales influenced by classical Noh theater. In the title story, which you can read here, a girl’s head flies off into the night to visit her beloved while her adoptive father molests her headless body. “As always,” he says, “the surface of her neck felt like a wet lip. I discovered that the headless body would surge with pleasure if I licked the wet part. Li’s head never seemed to know anything about this. Her body was unable to inform her head of its nightly experiences.”

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, trans. Keith Gessen & Anna Summers, There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby

Petrushevskaya’s “scary fairy tales” are like dark spells themselves. As Gessen and Summers put it in the book’s introduction, Petrushevskaya uses the classic nekyia, Homer’s night journey, as a unifying concept:

“In this collection, nearly every story is a form of nekyia. Characters depart from physical reality under exceptional circumstances: during a heart attack, childbirth, a major psychological shock, a suicide attempt, a car accident. Under tremendous duress, they become propelled into a parallel universe, where they undergo experiences that can only be described allegorically, in the form of a parable or fairy tale. … What happens to these characters on their journey in a strange land may be read as a dream, a nightmare caused by shock, or else a momentous mystical transgression—Petrushevskaya makes a point of leaving room for both interpretations.”

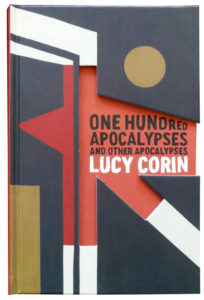

Lucy Corin, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

I could make an argument that every fairy tale is an apocalypse—an apocalypse of childhood, often, or an apocalypse of a certain way of life, a certain understanding of the world—but does it follow that every apocalypse is a fairy tale? Perhaps not (ask Buffy), but many of the vignette-sized apocalypses in Corin’s collection are—they are fairy tales of the every day, of the every moment, grand or quiet, destroying worlds or silences.

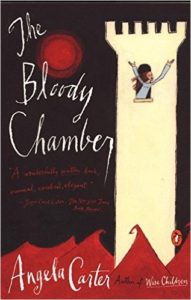

Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber

Well, you weren’t getting out of this list without Gothic feminist queen of your soul Angela Carter. You knew that, didn’t you, children? Famously, Carter didn’t consider these stories “versions” of the original tales, but rather, she sought to “extract the latent content from the traditional stories.” Latent, indeed: this book contains sadism, rape, murder, necrophilia, mother-as-handsome prince, a girl who becomes a tiger, a girl who uses her hair as a garrote wire, a girl who feeds her grandmother to the wolf, and so on and so on.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.