There are certain things that happen in the world, certain big events that make everyone ask afterwards: Where were you when . . . ? What were you doing when . . . ? What were you doing when Kennedy was shot? Where were you when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor?

Well, to that second question I can answer: Easy, I wasn’t around, not by a long way. But I know where my grandparents, Carlos and Teresa, were. They were in Manila. What were they doing? I can’t say. Perhaps they were doing what my Grandpa Carlos called ‘jiggy-jiggy’. That’s what he called it when I asked him once, when I was small, how babies got made. I don’t know why I thought my Grandpa Carlos might best be able to tell me. But he said, without thinking about it for very long, ‘Well, little Lucy, grown-up people—a man and a woman—they have to do jiggy-jiggy.’ The next question was obvious: ‘What’s jiggy-jiggy?’ Grandpa Carlos said, ‘Perhaps you should ask your mother.’ Then he gave me a wink. He made me feel that jiggy-jiggy must be a nice thing. Or perhaps he was winking at the awkward spot he’d now got his daughter, my mother, into.

But Grandpa Carlos liked to give me a wink about lots of things, sometimes for no reason at all. He had a face that would now and then twitch. It would just twitch. So perhaps his winks were sometimes just twitches. He had a face that could make people think that he was Chinese. He once pretended that he ran a restaurant in Gerrard Street. I can’t remember now if I ever did ask my mother.

Perhaps not. But after Grandpa Carlos’s funeral, not so long ago, in Swiss Cottage, I told my Grandma Teresa about how he’d told me about ‘jiggy-jiggy’—that he’d used that word when I couldn’t have been more than six. And this made my grandma laugh—after her husband’s funeral. We’d all gone to her place, though it still felt like ‘their place’, for tea and cakes. My grandparents loved their cakes. My grandma, who’s gone now too, said, ‘Well, Lucy,’ (I was no longer ‘little Lucy’), ‘I think he might have learned that expression from all the whores in Manila. They used to call out to the GIs, “You want jiggy-jiggy?”’ Then she said, ‘That was before Pearl Harbor. Now don’t ask me anything more.’ As if I’d suddenly become ‘little Lucy’ again.

It was the only time I ever heard my Grandma Teresa mention specifically any of the big events of history, or that I saw, quite clearly in her eyes, almost breaking their surface, the knowledge of terrible things that I must, still, never ask about. All my life, I’d never asked. Though by then I was a grown-up woman in my thirties and, once when I was small, I’d asked my Grandpa Carlos how babies got made.

But I’d made her laugh.

‘Have some more walnut cake, darling.’

And I like to think that when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor my Grandpa Carlos and my Grandma Teresa were doing jiggy-jiggy—while they still, as it were, had the chance. It would have meant that they were at least getting in practice for making my mother, Carmen. Though that would prove to take a long time, since when the news got through, about Pearl Harbor, they must have thought: Well, now life is really going to change for us. It might be going to change very badly, so badly that it might not be a good idea to be even thinking of making any babies. The world’s not going to be a good place to bring them into.

And they would have been right. Very right. There was a great deal that my Grandpa Carlos and my Grandma Teresa never told me. Or told my mother. Or, if they told my mother, that she never passed on to me. There was a great deal that would have made it very sensible indeed not to be even thinking of making babies. Though when my Grandpa Carlos told me about jiggy-jiggy, he didn’t say that when you did it, you had to be thinking, necessarily, of making any babies at all.

My mother, Carmen, wasn’t born till 1944, when it still wasn’t a good idea, even less of a good idea, to be having babies. So I think she was an error. Another mouth to feed when, so I’ve come to understand, thousands of people were starving to death. Error or not, she survived, as did my grandparents. I think that may be the best and rather miraculous description: they survived.

And my mother didn’t waste any time in having a first baby of her own. I don’t think she was very interested in the lessons of history. And by then—how the world can change—she was living in London, the Beatles were singing ‘Please Please Me’ and, so I understand too, there was quite a lot of jiggy-jiggy. I think I was another ‘error’.

So, as for the other question—where was I, what was I doing when Kennedy was shot?—that’s easy too. It was 22nd November 1963. It was my birthday, my actual birthday. I didn’t know about Kennedy being shot in Dallas, because I was busy being born in London. My mother was busy too. I was brought into the world on the day that JFK was killed. Does that mean anything? Has it in any way influenced my life? Who knows? But for my two examples of big events that have happened in ‘the world’, I seem to have picked out two catastrophes that were particularly American.

Not to mention the surrender of the Philippines.

And now I’m getting on for forty. A tricky time, possibly even a too-late time, for a woman, in the baby-making department. But I’ve had my babies. Two. Andy and Jane. Neither of them errors. So, yes, I know all about jiggy-jiggy. And my babies are old enough now to be doing jiggy-jiggy themselves, even to be having babies. They’ve never asked me any awkward questions about how they get made. Times have changed again.

But though my babies are grown-up, I can still think of them as just babies. They wouldn’t like to know this. I can still think of wrapping them in blankets. Because the world doesn’t get any safer. Clearly. And though I’ve been, myself, through the process of motherhood and I’m getting on for forty, the maternal instinct remains strong in me, just as strong, perhaps, as when I was actually having babies.

That’s why when Mrs Olson asked me suddenly if I wouldn’t mind looking after Danny for a while, if I wouldn’t mind taking him out somewhere, it was such a nice day, I said, ‘Of course, Mrs Olson. No problem.’

But now I won’t be seeing Danny again. I’ve seen the last of all three of them. It was the end of Mr Olson’s posting, and they’ve gone. What timing! Though who could have known? And how did Mr Olson get his posting in the first place? London, for a year. So early in his career. If you ask me, there were ‘connections’ at work, strings pulled. In Washington.

And where’s he going to get sent now?

In any case, that poor kid, Danny, was never going to know where he belonged in the world, except to be carted round it, like a piece of (very expensive) luggage, with them. I think that, after a whole year, he’d just been starting to realise it. A year’s a long time if you’re only six. They were getting ready to go back home. Meanwhile, he’d been turning into quite a little English boy.

*

‘Of course, Mrs Olson. No problem.’

Though I’m not his mother, I’m not a nanny. That’s a whole other arrangement.

‘You’re an angel, Lucy.’

I’m just the maid. At Number 8.

She’s already getting ready to go out. She’s been on the phone for most of the morning. As she talks to me, she looks at herself in the big gilt-framed mirror, running a fingertip over an eyebrow, patting her hair. She’s decided to get her hair done, though her hair looks fine. Then to meet a friend—Kitty Boyd—at the Grosvenor, for a drink and a bite. A ‘farewell drink’. The day’s already turning into a whirl.

Danny stands beside me as if his mother might be talking to him through me.

Mrs Olson, Nancy Olson, I’ve learned by now, is an impetuous woman. Not the best woman (in my opinion) to be a junior diplomat’s wife. She’s apt to tell me, and her son, what she intends to do only moments before she does it. But today is a special day, I grant her. It’s not like any day (and neither of us yet knew the half). They have only three days to go, and this evening her husband is getting a leaving party. She doesn’t need to get her hair done, or to meet a friend for lunch and so leave her boy in the lurch, in my hands. But why not? She’s free to do all these things.

And, looking back now, I can say that, yes, she should have made the most of it, made a whirl of it, while she could.

Kitty Boyd? I know her. I don’t mean I know her, of course not. I mean I know who she is. One of the Embassy wives, one of the longer-term ones, the taking-under-the-wing ones. They’ll be seeing each other at the party anyway, but they’ve fixed up a separate one-to-one. Why not? And why not get your hair done, into the bargain? A last hairdo in London.

‘No problem, Mrs Olson.’

Mrs Olson is in a whirly mood and while she looks at herself in the mirror, I look at Danny, and he gives me a wink. It’s a very quick wink, just a flicker of the eyelid, only meant for me. But the wink means something like: My parents are complete airheads, aren’t they? The wink is anyway quite a happy wink. And I wink quickly back.

I’m not always sure what my winks at Danny mean, but in this case my wink means: Well, come on then, Danny, let’s go and make the most of it. Before you’re gone and we won’t see each other again. Before I start to miss you.

Which I already do.

Some while ago, he started to call me—never when his parents could hear—‘Auntie Lucy’. And he’d say it with an English voice, in a crafty English way. Yes, he’s always going to have inside him, even when he’s getting on for forty like me, a little English boy. His first posting too. It will stick. Not just a little English boy, a little Londoner, with some of the lingo. ‘Gissus a kiss.’

And he started to give me those secret winks, and so to remind me, just a bit (though I never told him), of my Grandpa Carlos. Though he was Filipino, but spoke English. I am English. The world! What a mix-up. And Danny wasn’t a grandpa, he was only six. It was the other way round. It was for Danny to ask me, his Auntie Lucy—if he felt like it—how babies got made. But perhaps, though he’s only six, he doesn’t need to.

In fact, I’m pretty sure, now, he doesn’t need to.

I’m just the maid—the ‘Filipina maid’. But I’m English, like my parents. I can’t help it if I have some of my grandparents’ looks. And I’m not any ordinary sort of maid. I’ve been the maid at Number 8 for most of ten years. They call it sometimes ‘Number 8’, sometimes ‘The Crescent’. It’s just one of their places for staff above a certain level. I wouldn’t have said that Mr Olson—Todd Olson—was above that level. Just a new kid on the block. But there we are: connections, strings. He must have swung it. Someone, in Washington, must have swung it for him.

And he must have said one day, over a year ago now, to his all-ears wife, ‘And we’ll get a house overlooking Regent’s Park.’ And might have added, ‘With a maid.’

And maybe, after that bit of news, the two of them did some quick jiggy-jiggy—if little Danny wasn’t in the way. London! At his level. So: a blue-eyed boy. And Number 8. With the cream stucco and the portico and the railings. Not a palace, but a fine house. And ‘overlooking’ would be a stretch. Of the neck. They were lucky to get it.

And I was lucky, too, to ‘get’ it. I know it inside-out by now. Sometimes, though I never say this to anyone, I think that it belongs to me. I belong in it, and it belongs to me.

But it actually belongs to the American Embassy. (And where I actually live, with just Rick now and no longer the kids, is Camden.) I’m not an ordinary maid. I get paid much more than an ordinary maid, and I get paid by the US Embassy, in English pounds. And though I do a maid’s work, I have to do it with an extra degree of responsibility, discretion. And I have to do certain, not always specified, things that are beyond a normal maid’s work.

Though they shouldn’t include being a child-minder.

That’s a separate set-up.

Usually, though I’ve never said this to the Olsons, the ones I ‘look after’, the ones who qualify for Number 8, are of the senior, silver-haired kind. No small kids in tow. And what are wives for? What are Embassy wives for? To be shopping at Harrods and getting their hair done all the time? No, Mrs Olson—you go and take little Danny to see the changing of the guard.

Nonetheless: more than just a maid. Part maid, part caretaker. Part everything. You have to show them the ropes. And, of course, you have to speak perfect, fluent, educated English. Which I do. Of course I bloody do. I’m not a ‘Filipina maid’.

Though when I got the job, all those years ago, things were different. I already had plenty of general maid’s experience and good references, but I had to be vetted. Not just interviewed, vetted. And I played the ‘Filipino’ card then. You bet. I said that my grandparents were Filipino. Real Filipino. But that they’d always worshipped America. I think I might actually have said ‘worshipped’. Because America had saved them. They were there, you see, when the Japs arrived. And they were still there—or just about still there—when the Americans came back to kick the Japs out. Oh yes, they could remember General MacArthur. With his corn-cob pipe. Keeping his promise. My grandparents had always loved and been for ever grateful to America. They’d wanted to go to America. But they only got as far as England.

So here I am—English myself—wishing to be of service to the American Embassy.

I played the Filipino card. And most of it true. Though you could say that in order to ‘save’ my grandparents, the Americans had abandoned them in the first place, for three years. And I never said—but my Grandma Teresa hadn’t told me yet—that my grandpa could remember all the prostitutes calling out to the GIs.

And maybe it swung it. It got me the job and the money. And maybe little Danny swung it for Mr and Mrs Olson, without ever knowing it. Maybe Mrs Olson had said to her husband, ‘Well, Danny’s going to need a proper bedroom of his own, isn’t he? They can’t just give us some apartment.’ So—with whatever other string-pulling—they got the house. They got Number 8. And they got me.

But the world? That’s not my job. I look after the house, so they can look after the world.

*

‘No trouble, Mrs Olson.’

It was September. The sun was shining brightly over Regent’s Park. In three days’ time they were going back to Washington. But, first, Mr Olson was getting a leaving party, a send-off. If he was getting a leaving party, then he couldn’t have messed it up, he must have earned his spurs. A leaving party and a sort of launch party—for his future career. And Mrs Olson was making a day of it.

‘That’s fine, Mrs Olson. I have a feeling Danny might like one last visit to the zoo.’

I was looking at Mrs Olson now, so I couldn’t give Danny any more winks.

‘The zoo! Well, yes of course. What a great idea. Why didn’t I think of it?’

A good question. Why didn’t she? Danny’s attachment to the zoo, just minutes away, was by now very established. He was going to miss it. He was too young to go there by himself, close as it was. So guess who mainly took him.

But I didn’t say anything. I could sense Danny’s unspoken ‘Thank you, Auntie Lucy’. He didn’t quite—in front of his mother—squeeze my hand. I gave a little cough. A practised, patient maid’s cough.

Mrs Olson said, ‘Oh—yes, of course, Lucy.’

She fetched her handbag and fished out some notes. She was well used to English money by now, but not to the price of everything. Her eyes showed it. Two tickets to the zoo, one adult, one child.

‘Oh, and you must get him something for lunch. And an ice cream or something.’

Plus one, two sandwiches. Plus one, two ice creams. ‘That’s plenty, Mrs Olson. I’ll bring back any change.’ She waved her hand. She looked at her watch.

‘So—I’ll be off. I’ll grab a cab. I should be back by three.’ Then, as if she’d almost forgotten her son, or his total compliance was assumed, she said, ‘Be good, won’t you, Danny? Have fun.’

No little kiss.

She dallied in the hallway for a moment, to put on the black jacket that hung on the stair post. In the hallway were several small English landscapes and, opposite another gilt-framed mirror, a quite large painting of a vast herd of buffalo crossing some western plain. Every item of furniture in the house was on my mental list. I wondered how much the Olsons would remember any of them.

But Danny would remember the zoo. I knew that he would be only too glad of his mother’s suddenly busy schedule that made this last visit possible. And only too glad of having his Auntie Lucy to swing it. Otherwise, he might have been forced into the position of pleading at some point directly with his mother: ‘Mom—can you take me, one last time, to the zoo?’ And got no joy.

It might not have meant much to Mr and Mrs Olson, but it had begun to mean a great deal to Danny. They’d come to London and hadn’t known that, just across the road (so to speak), they were going to get lions, tigers, elephants—you name it. And he was going to get his Auntie Lucy to take him, several times, to see them. Lions, tigers, all kinds of animals, including, as it happened, in a drab enclosure and always seeming very displeased with his situation, an American bison.

‘He doesn’t look very happy, does he, Danny? Do you think he has a name? What shall we call him?’

‘Bill.’

What a smart little boy. It became, on every visit, a sort of ritual, to go and see Buffalo Bill and try to cheer him up. And now Danny could say his goodbye to him, since Buffalo Bill wasn’t going to be doing any going back.

We’re going to live in London, Danny! So they must have announced once. We’ll show you all the sights of London! They would show him? They hadn’t even known that the London Zoo was in Regent’s Park, and certainly hadn’t known that, of all the sights of London, the zoo would be the one their son would most want to see. And keep on seeing.

Though can you call the London Zoo one of the sights of London? Since it’s really the sight of all the animals that come from everywhere else in the world, anywhere but London. And this would be the same for any zoo. Wasn’t there a zoo in Washington? A zoo is a sort of prison for the rest of the world. Which is not a very nice idea at all.

But a zoo is also—just a zoo. Where you can buy a ticket and go through the turnstiles and see all the amazing animals and even lick an ice cream while you do so.

‘Come on, Danny! Get yourself ready.’

How many times, in the course of a year? Once or twice with his parents, perhaps seven or eight (if only to get him off their hands) with—his auntie. And, now, one last time. His own ‘leaving’ party.

I still had maid’s work to do around the house. Well, too bad. Mrs Olson seemed not to have considered this. I’d have to catch up later.

It was a little after eleven-thirty. Barely dawn in America. Eastern time. Part of the job: always have in mind what time it is in Washington.

Mrs Olson would soon be sitting, wrapped in some gauzy pink covering, at the hairdresser’s while her son and his Auntie Lucy (she had no idea that her son called her that) would be wandering among the cages.

Come on! Let’s go and see some animals!

As we left Number 8, he reached out his hand for me to take. When had he first done that? When had it become that way round? One last visit. But let’s not get all sad about it, Danny, it’s a lovely morning and here we are again. What shall it be? Buffalo Bill, of course, but then what? The lions and tigers? The penguins? The monkeys? The fish? The creepy-crawlies? We can’t see it all.

Of course not. Not in one go. Though, in a year, we must have done it all, more or less. So I, his Auntie Lucy, had become quite an expert on what there was to see. And, of course, zoos are supposed to be ‘educational’. They—the Embassy—had fixed up for him, since he came, necessarily, with his parents, some elementary (but quite superior) schooling. Though wasn’t the principal lesson to be had in the London Zoo?

Well, I hope, Danny, it wasn’t too much of a cage for you, your London cage. The first of many. All of them very comfortable, expensive and safe. Safe? I hope I made Number 8 quite a nice cage. Your first one, so the one, perhaps, you’ll most remember. And I hope you’ll always remember anyway—but I think you will—our ‘escapes’ to the London Zoo.

We made no particular plan, we followed our feet. Of course, we said hello—and goodbye—to Buffalo Bill. There he was, in his mangy coat, slumped on his folded legs, his huge grumpy horned head looking back at us for a while. Did he recognise us? You couldn’t help feel it. Was he thinking: There are those two again? You couldn’t help wondering what all the animals were thinking, looking back at the people looking at them. Though a lot of them didn’t do any looking back at all.

Have you noticed, Danny, that when the animals look back at us, they all look back with the same look in their eye?

And, perhaps inevitably, we finished up with the monkeys. The monkeys were nearly always active and could be relied on to give good value—to swing and jump about and screech and chatter and generally look as if they were happy to put on a show. The monkeys, on this last visit that must have its touch of sadness, would be most likely to make us laugh.

And then I bought sandwiches—seeing all the animals getting fed made you hungry too—and, yes, we had ice creams. We sat at a wooden table, licking ice creams, a woman of nearly forty and a boy of six, both of us, perhaps, having the same thought: We might be animals, ourselves, in some enclosure, doing this, being looked at. This is typical behaviour of the human species.

What were you doing when? Where were you when?

Had there been some strange ripple running round the outdoor café, round all the people who’d decided on this day to come to the zoo? Had we noticed something, apart from the antics and sounds of countless animals, starting to create a stir around the zoo?

I must have looked at my watch, and said, ‘Well, we best be getting along, Danny.’

He said, ‘Gissus a kiss.’

And when we got back, all hell had broken loose. Mrs Olson had returned, her hair immaculate, but her general appearance very much not. The television was on. It was about half past two. And there were pictures, terrible, unbelievable pictures, coming from New York, that were going to be repeated over and over again, as if repeating them would make them less unbelievable. They were being seen, already, all over the world.

In New York, in Washington it would still be half past nine.

Mrs Olson said, ‘They’ve cancelled his party. Just cancelled it! Well—what can they do?’ Then she said, ‘They had the TV on at the Grosvenor. In the lobby. In the bar. They had the fucking TV on!’ And then she said, her eyes not turning from the TV at Number 8, ‘What now?’ And she kept on saying it. ‘What now? . . . What now? . . . What fucking now?’

And Danny said, ‘Do you want to know what we saw at the zoo?’

Mrs Olson said, ‘Todd said he can’t come back here. Not now. He has to stay at the Embassy. He said they’ve gone into some kind of mode. Some kind of mode!’

It was as if she’d wanted him to be there—for her. She seemed not to have noticed—not even heard—her son, her little boy, Danny, who might have wanted his mother to be there for him.

‘Mrs Olson, did you get any lunch? Can I get you anything?’

‘Lunch? Fucking lunch!’ Then she said again, ‘What now? . . . What now?’ And kept on repeating it, like the pictures being repeated on the TV.

Where were you when? I was in a hotel lobby in London, having just had my hair done. I was looking forward to the evening. I was having a good day, I was looking forward to lots of things. I was looking forward to going back home again to the States.

Yes, the monkeys were quite active. As if they appreciated—but it must always seem like it—all the people who’d come to see them, and they were glad to perform. Two of them were being particularly active. And this was making some of the people laugh and squeal at each other or clamp their hands over their mouths, and behave a bit like monkeys themselves.

In all our visits to the zoo, we’d never witnessed such a thing before, which, if you think about it, was quite surprising. But there it was, happening now, on this last visit. I wasn’t in the least embarrassed, standing beside Danny, holding his hand. Perhaps I was even smiling to myself and thinking of a time, long ago, when I’d been roughly his age.

The question was: Was he going to say something, ask something? Yes, he was.

‘What are they doing, Auntie Lucy?’

Was it an entirely innocent question, or did he just want to know how I’d manage? Was he having fun with me, as all the people were with the monkeys?

‘Well, Danny, they’re doing—jiggy-jiggy.’

Did I keep a straight face?

‘What’s jiggy-jiggy?’ I didn’t hang back. I didn’t say, ‘Ask your mother.’ Definitely not. I gave him something to think about, quite an education.

I said, ‘It’s something animals do, Danny. As you can see. In fact, it’s something people—grown-up people—do as well. Because, after all, people are animals too. We’re all animals too.’

He clutched my hand.

I suppose there would have been monkeys in Manila, and I suppose that, back in those dark days, Grandpa Carlos and Grandma Teresa, if they were lucky enough, might have eaten them.

‘Auntie Lucy—is jiggy-jiggy how babies get made? Is it how babies get brought into the world?’

He actually said that. He used the words ‘brought into the world’. With his nice English accent. In a few days’ time, he knew, he’d have to be American again.

What a smart little boy. How could he have come to ask such a remarkable—and highly relevant—question? And he even answered it himself.

‘It’s how babies get made, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, Danny, it is. How did you know?’

‘Oh, Auntie—I think I just knew it. I think I just knew.’ He might almost have said, ‘I wasn’t born yesterday.’

__________________________________

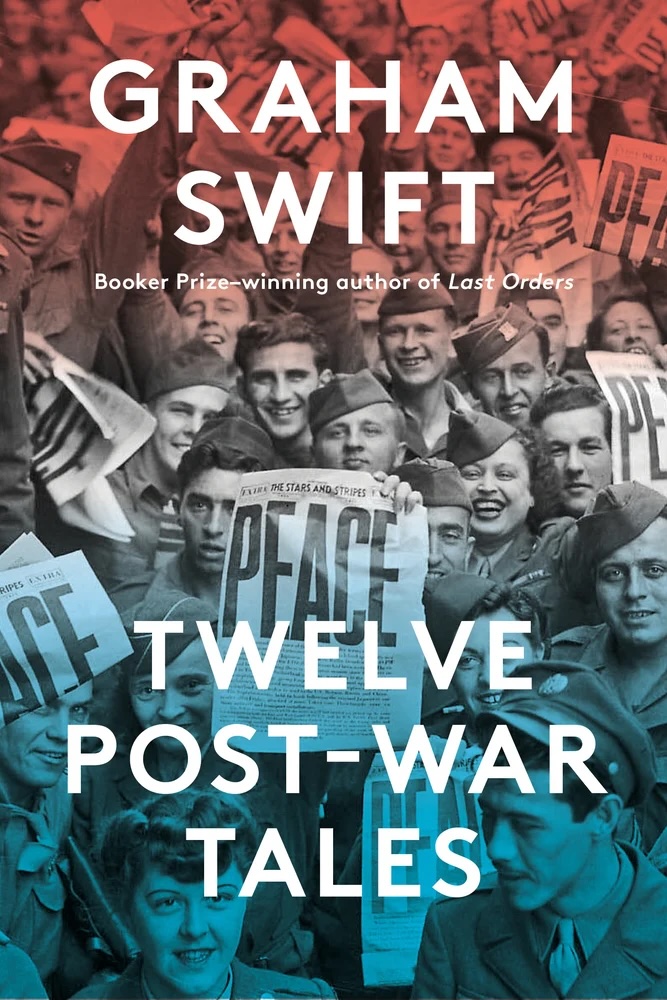

From Twelve Post-War Tales by Graham Swift. Used with permission of the publisher, Knopf. Copyright © 2025 by Graham Swift.