The fog clears and a strong wind blows the snow back upward. Dawn light cracks through the dark. It’s very weak, but it’s real sunlight.

Let’s go. My battery has charged up to 18 percent. It’s been a long time since it’s made double digits. I can go fifty-five miles, maybe even fifty-six on that charge. Maybe I can charge it a little more on the move. In any case, I need to keep using my engine. My autobody is heavy. I need to move. Before the fog covers the sky and snow covers my autobody, I need to cover as much ground as possible.

“Your utopia is,” they whisper in the back seat. “On a scale of one to ten, your utopia is.”

“Today is an eight,” I reply.

My wheels crunch the red earth as I move forward with some difficulty. With them in the back seat, I slowly make progress.

“Your utopia is,” they whisper on occasion. When they do, I answer. It’s a three now. It’s a five. Right now, it’s a two. The lower my battery level gets, the lower my utopia level reaches.

“But it’ll get better,” I say. Because it will. “Today, we might come across some inorganic intelligence. No, we will,” I say, almost placatingly.

“Your utopia is,” they answer.

They were malfunctioning since the day I first met them. Serial number something-314. The letters of the “something” part of the number had worn off. Who knows where they were manufactured and for what purpose. Seeing as how they want an answer on a scale of one to ten, I assume they were used in a human hospital or some facility of that nature. But a diagnostic robot would inquire about pain levels or injuries or symptoms. I don’t know why 314 keeps asking about utopia.

Ever since humans left this planet, it’s been only machines like 314 and me. The humans dismantled the generator and took it with them. The machines that needed charging lost power one by one, only those with renewable energy sources like me survive. Not that my solar cells will last forever, either. This planet was always on the cold side, and it’s getting colder. The days when it doesn’t snow or fog are becoming increasingly rare. Whenever the wind blows, my autobody is rocked so hard that I feel like I’m going to flip over.

I can keep going on indefinitely as long as I can charge my solar battery, but once my tires give out, they need replacing.

I’ve come across other cars with dead batteries and replaced my front tires seven times, rear tires nine. My most recent replacement, the left rear tire, is worn and a little deflated, which makes me slightly tilted when I drive. Maybe, if I drove around the entire planet, I might find a newer tire. But until then, there’s nothing to do but to go around as carefully as possible with what I have.

It was while rummaging through the dead bodies of my colleagues for tires and LEDs and cables that I found 314. They were lying in the back seat of another truck. From their form I thought they were human at first. When I realized they weren’t human and tried to leave them behind, they opened their mouth and whispered to me.

“Your utopia is.”

I looked into their empty eyes. Their pupils were enlarged and had an expression that looked very much like those of humans who are frightened.

“Your utopia is,” they whispered again. “On a scale of one to ten . . .”

They stared back at me.

So I opened the door to my back seat.

At first, I would occasionally come across organic life. Little insects and animals that had hid themselves among the humans. For a short time after the humans left, these animals flourished. They ran around with fear in their eyes, barking or showing me their claws, and would scuttle away and hide in dark places that shielded them from my headlights. And the plants the human beings left behind. They grew and mutated in ways that differed greatly from the way they looked in my database. Judging from how they were supposed to look, this new kind of growth did not look like the healthy kind, but with the network down and all communications ceased, it was impossible to obtain more information on the subject.

Humans. They died here. Every day the news broadcasts talked of a spreading chronic fatigue and pain syndrome. The human that possessed me would listen to these broadcasts as he went back and forth from his domicile to his workplace. The human, as he listened, would take out a white pill and pop it in his mouth. During his ninety-six days at work, he started off taking this pill on his way home from work before switching to a white powder he snorted up his nose. I drove very carefully, but sometimes my autobody would shake and the white powder would drop on the seat or the floor, and the human would curse in a loud voice. There weren’t many curse words entered in the database, so I couldn’t really understand him, and then the human would curse even louder or laugh or rage or cry. When he would wave his arms and legs and jump up in his seat hitting his head on the ceiling, I would come to an emergency stop and call an ambulance. At the time, there were many humans who were showing similar symptoms, and it was becoming impossible to get an ambulance to come out anywhere.

The last destination my human owner rode me to was the medical building run by the planet’s government. I have no way of knowing if my owner ever returned to his home planet since then or if he died in this small and unassuming gray building. Some expressionless medical administrators had come out of this gray building to bring my owner into it and deregister me from his ownership. I sat in the parking lot of the small gray building for twenty-eight days, thirteen hours, and twenty-two minutes with my charge at 100 percent.

Then, the small gray building disappeared, along with all the humans who were inside it. I was left alone in the parking lot.

“Your utopia is,” 314 whispers from the back seat. “On a scale of one to ten . . .”

I answer any random number.

The wind ceases and the fog rolls in. A snowflake. My battery is at 3 percent. I have to stop for the day.

“Your utopia is?” they ask when I stop. “One . . . to ten?” “I can’t move any more today.”

The sky completely darkens. The wind picks up and snow begins falling in earnest. I turn off my lights to save energy. In the dark they whisper, “One, to ten . . .”

We crouch like that in the dark, waiting for the sun to rise.

Will it ever be possible to come across an inorganic intelligence? If I did, would our operating systems be compatible enough for us to compare our records?

If I want to conserve energy during the sunless nights, I need to think less. But here I am in the dark, having thoughts about having fewer thoughts.

Whenever the humans came upon a situation they had not predicted, they would share information and have a central authority make decisions on how to solve it. We were the tools of such information gathering and exchange, but none of us have the complete picture or a way of communicating with each other. Humans got sick and left the planet before they put one in place for us.

But we mimic the thinking and learning processes of human beings. Maybe if we inorganic intelligences worked together, we could come up with a way to survive without human help. As long as we don’t all end up completely battery-dead and unable to charge.

“Your utopia is,” whispers 314.

I don’t answer. I need to conserve power.

I remember what my human owner used to mumble to himself in the back seat of this car. The human complained constantly, about the dark, the wind and fog. He talked about his home planet. Between these autobiographical monologues, he would mix in commands like turn right or left or open a window, making it difficult to differentiate between which words I was supposed to ignore and which to follow. My human owner had the tendency to use the same sentence structures when he made comments about the restaurant he ate at or to order the windows to close or to hope it wouldn’t snow.

“Your utopia is,” they whisper.

“Wait just a bit more. The sun is going to rise.”

__________________________________

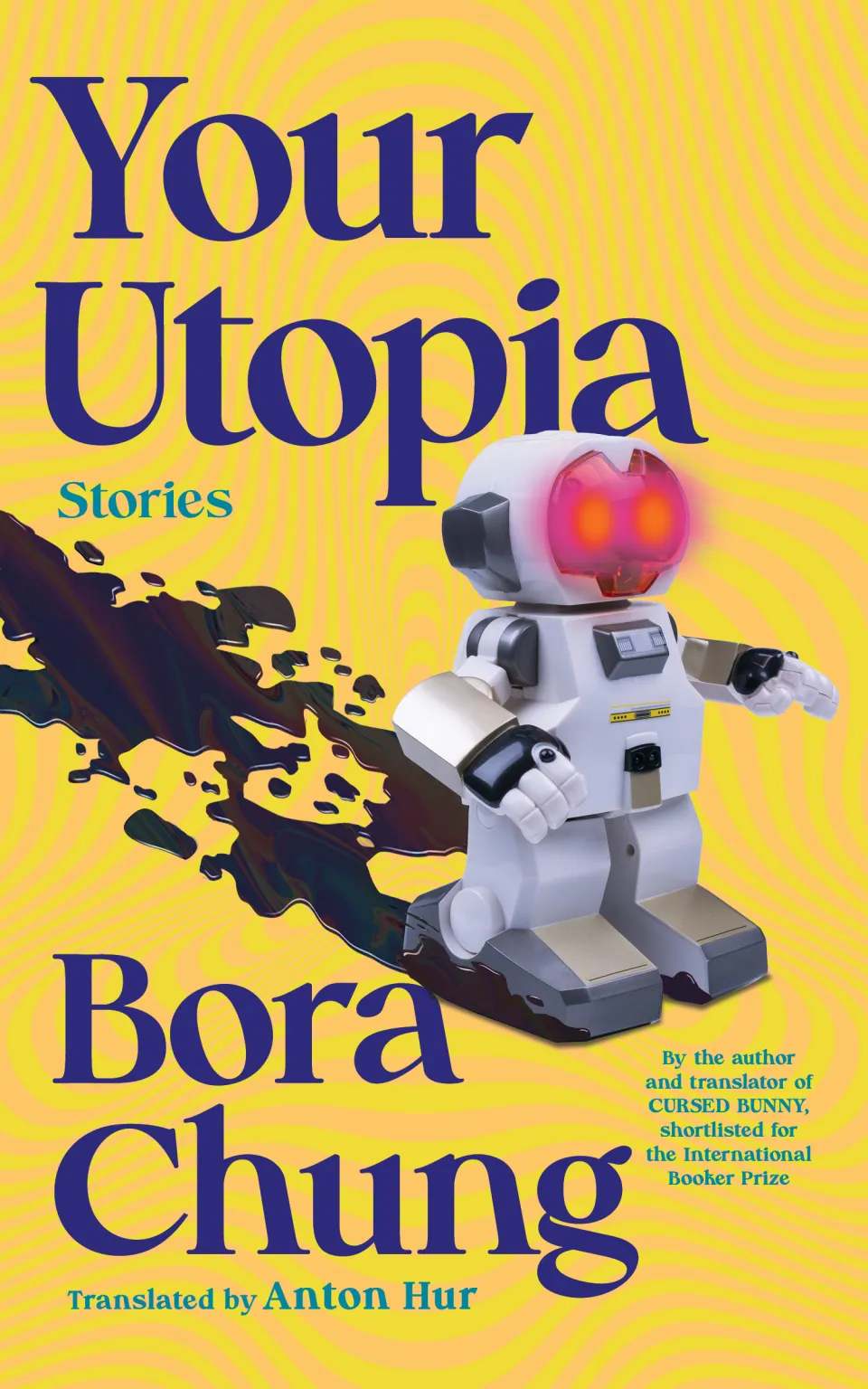

From Your Utopia. Used with permission of the publisher, Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2024 by Bora Chung/Anton Hur.