I’ve moved to this city to wait for the end of the world. The conditions couldn’t be better. The apartment is on a quiet street. From the balcony you can see the river in the distance. You can also see it from the small kitchen patio, which overlooks the back gardens and balconies along the adjoining street, the enclosed balconies with iron railings where clothes are hanging, fluttering in the breeze. At the end of the street, beyond the river, the horizon of hills on the other bank and the Cristo Rei with his open arms, as if he were about to take flight. In Siberia there are, at this very moment, temperatures above one hundred degrees Fahrenheit. In Sweden, fi res fueled by unprecedented heat ravage the forests that extend above the Arctic Circle. In California, fi res spanning hundreds of thousands of acres have been raging for several months in a row, and they are given their own names, like hurricanes in the Carib bean. Here, days dawn fresh and serene. Every morning there’s a damp, bright-white mist the sun breaks through slowly as it carries the strong scent of the sea. Swallows skim across the sky and fly over the rooftops, like they did in the cool summer mornings of my childhood. As soon as Cecilia arrives I won’t need anything else. The end of the world has most likely already started, but it still seems far away from this place. Airplanes fly in all day, from before dawn until after midnight, coming across the sky from the south, just above the Cristo Rei, spreading his reinforced concrete arms out like a superhero about to launch himself into the air. Immense cruise ships glide up the river, looking like vertical housing developments for tourists, floating replicas of Benidorm or Miami Beach. There’s nothing better to take your mind off waiting than to look out over a balcony or a park railing and watch the ships pass by on a large, sea-wide river. Light sailboats and tankers with rusty, cliff-like hulls drift along. From a nearby street I can see the container wharf crane along the shoreline of the river. In the glare of the nocturnal floodlights, the crane moves back and forth like a robotic spider, one of those spiders grown monstrous from the effects of atomic radiation in some futuristic movie from the 1950s. From the kitchen patio, where Cecilia and I will soon start planting vegetables in raised beds filled with fertile soil, above the balconies and rooftops and the brick chimney of an old factory, I can see the top of one of the bridge towers, faded red against the soft-blue sky. The always-present background rumble comes from the traffic on the bridge: the cars and trucks and the trains on the lower deck; and there’s also the vibration of the pillars and metal plates under the weight and tremor of the traffic, and the cables quivering like harp strings in the wind. The bridge and the whole river and the hills on the other bank and the container wharfs and the Cristo Rei, I see all of it every morning from the little park where I take Luria for a walk. If I walk beside her, she sniffs through the bushes, runs behind the pigeons, digs and plunges her snout into the ground. If I sit on a bench and stare out at the river and the incoming planes, Luria sits at my side contemplating the same spectacle in a perfect wait-and-see attitude, her nose raised, her gaze fixed on a distance that her myopic eyes will only vaguely be able to make out. If I pull a book out of my bag and start reading, she seems to take over for me, and her attention intensifies.

*

Maybe I’ve settled into this new life so quickly because there are a certain number of things in common with the one we left behind. Maybe the similarities influenced us unconsciously when we chose this part of the city and this apartment. Every day I observe repetitions and echoes that I hadn’t noticed before. Most of our decisive mental operations take place in the brain without our consciousness being aware of them, Cecilia says. The Cristo Rei on the opposite riverbank was a disturbance at first, a mistake on the landscape: the first day in our Lisbon hotel, Cecilia opened the window and saw it in the distance and because she was still a little dazed from jet lag, she told me that for an absurd moment she had the mistaken impression that she was in Rio de Janeiro, where she had been a few weeks earlier for one of her conferences on the human brain. Then she had to come to Lisbon, and it was on that particular trip I was able to join her. She would attend her scientific seminars and I would wander around the city and wait for her at the hotel or in a café, relieved not to be in New York and that I wasn’t working. The hotel was quiet and tidy, like one of those friendly English hotels, not a real one but one from some movie, with clean rugs and no musty smell. We opened the curtains in the room when we arrived and we saw the river and the piers all at once. There was a library on the third floor with dark, wood-lined walls, old leather armchairs, a fireplace, a gilded copper telescope, a large picture window, a terrace facing the river. The bridge loomed in the background. The strands of lights came on early in the December dusk, in a drizzling fog. Huddled in bed as if inside a burrow, we listened to the bells, chiming in a church tower and announcing each hour. Sated afterward, appeased, hungry, we went out to search for a place to have dinner, along uninhabited, scarcely lit streets. The white-stone sidewalks were slippery with the condensation from the mist. It didn’t seem likely that we would find a restaurant in such an out-of-the-way neighborhood and at such an hour. As we climbed a flight of steps we saw a lighted corner at the end of the street; a quiet murmur of voices, cutlery, and dishes trickled out of it. It was a low structure, like an unexpected country house, painted pink, with a bougainvillea covering half the facade and the window. When we came in from the deserted street we were even more pleased to see the animated diners and waiters. It was an Italian restaurant. There were a lot of people, but they were still able to seat us. The waiters, cordial and efficient, looked Italian, but they were all Nepalese. To have stumbled across that restaurant and then savor a flavorful pasta dish and an inexpensive light-red wine, some tiramisu, an ice-cold grappa, nourished our inner joy, our gratitude toward randomness, an unforgettable trattoria in Lisbon run by people from Nepal. Then we got lost exploring the unfamiliar places that are now part of my everyday life, the normal life we are about to begin in our quiet and sheltered wait for the world to collapse. “A river like the Hudson,” Cecilia said, a little drunk, happy, unsteady in her high heels on those climbs and descents, “a bridge like the George Washington Bridge.” In a nearby church a bell tolled the hour. “The clock tower like the one on Riverside Church,” I said: and at that moment, that night I never want to forget, in every one of its secret nuances, neither of us imagined anything yet, though it is possible that we passed along this street, under this balcony I am now peering over.

__________________________________

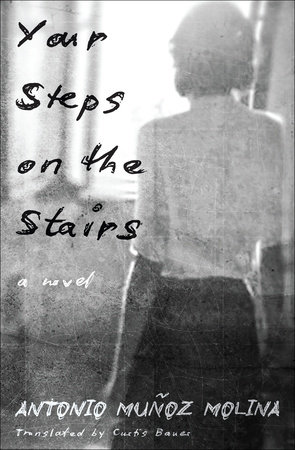

Excerpted from Your Steps on the Stairs by Antonio Muñoz Molina, translated by Curtis Bauer. Published by Other Press on April 8, 2025. Copyright © Antonio Muñoz Molina and translated by Curtis Bauer. Reprinted by permission of Other Press.