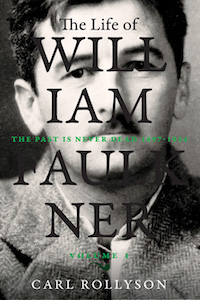

Young William Faulkner in the French Quarter

The Creolization of Faulkner's Writing

Spanish moss, rumbling streetcars, honking automobiles, street vendors, artists, prostitutes, nuns, tourists, speakeasies, restaurants, and bars—that was the New Orleans French Quarter in the 1920s, when Sherwood Anderson and his wife, Elizabeth Prall Anderson, arrived, settling into the Pontalba building, actually two four-story buildings on two sides of Jackson Square, built in the late 1840s by the Baroness Micaela Almonester Pontalba. Restaurants and shops on the ground floors and apartments above formed a kind of complex now commonplace in modern cities.

By the 1920s, the buildings, fallen into disrepair, began to be restored. This was not gentrification, exactly, but certainly part of a movement in New Orleans to honor its past and attract tourists and new residents to a city steeped in history. New Orleans was also a good place for a young writer to discover himself among other writers and artists, and for an older artist to renew himself.

From their high-ceilinged apartment in the Pontalba building, the delighted Andersons could see Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, and a sizeable sweep of the city. Faulkner, still a synesthetic poet and painter in Mosquitoes, described the conjunction of apartment building and cathedral as “cut from black paper and pasted flat on a green sky; above them taller palms were fixed in black and soundless explosions.” The images and metaphors, which perhaps owe something to Ezra Pound, a poet William Spratling said Faulkner revered, also testify to the powerful and lasting impact of New Orleans on a still-developing writer.

Climbing two flights of steep stairs to get a panoramic view, and to Sherwood Anderson, came all sorts, including William Faulkner. “Sherwood made friends with everyone, quickly and easily, and we soon knew all of New Orleans,” his wife wrote. “Anderson possessed an ineffable openness and sweetness that made him attractive to nearly everyone”—even the sour Theodore Dreiser. Anderson, with his penchant for dressing like a riverboat gambler, did not look like a literary man. He could connect you to the Double Dealer trio, Julius Friend, James Feibleman, and John McClure, who made the city a literary cynosure.

You could cast a play, or write a novel like Mosquitoes, with characters resembling artist William Spratling, a Tulane architecture professor with a defiant squint; another Tulane anthropologist, Frans Blom, staring at you in bright-eyed amazement; and the writers Roark Bradford, harassed with news items to edit in the Times-Picayune; Hamilton Basso flashing a handsome grin; and Lyle Saxon, journalist and bon vivant, somewhat aloof in his immaculate seersucker suit. In the background hovered lesser lights such as George Marion O’Donnell, who would write one of the first significant feature articles about Faulkner.

Hamilton Basso likened the French Quarter to “Paris in my own backyard.” Others congregated in the city after stays in Greenwich Village. But unlike bustling commercial Manhattan that encroached on Bohemia, New Orleans, surrounded by river, lake, and swamp, was an island of the mind, cosmopolitan but not industrial or conformist.

Anthropologist and novelist Oliver La Farge, a New England brahmin, “all head and thick glasses,” deserves honorable mention. He developed a camaraderie with Faulkner that foreshadowed the disruptive antics of Shreve McCannon in Absalom, Absalom! La Farge enjoyed getting drunk and indulging in racy talk with women nothing like Boston girls, who would not have dared to damage their prim personas: “I felt deliriously light, I seemed to be someone I had never been.” La Farge had first entered New Orleans during Mardi Gras time, which made the city the equivalent of sailing off on The White Rose of Memphis in costume, so to speak, masquerading as someone you were not but making what you were not a part of what you were.

Here, in New Orleans, a member of New England’s founding Puritan class consorted with a Creole, mixed-race culture.La Farge, handsome and outgoing, had many affairs with women, according to Harold Dempsey, another French Quarter regular. This was not the case with Faulkner, Dempsey said. He remembered La Farge showing up at party fully dressed in armor. A woman wanted to go upstairs and make love, but La Farge, even with Dempsey’s help, could not get off his equipment. But he went upstairs with the woman anyway.

Although reared in the abolitionist tradition, La Farge, like a good anthropologist, absorbed the ethos of southern life and decided not to protest racism but to probe the origins of his friends’ thinking. He estimated the arts colony as no more than 50 people, a small enough number that made him feel certain of his ground. “I don’t remember anyone cherishing the idea that he was an as yet unrecognized genius in our midst,” La Farge wrote, apparently unaware or having forgotten that Faulkner did sometimes present himself as such.

La Farge did, however, corroborate the commonly held view of the community’s solidarity: “When one of us achieved anything at all, however slight, the other workers were delighted, and I think everyone took new courage.” What La Farge said of himself could be applied to Faulkner: “I made more lasting friendships than I had made in the rest of my life.”

John McClure remembered watching Faulkner and La Farge saunter down a street boisterously singing a dirty ditty, “Christopher Columbo,” parts of which are worth quoting because they capture the flavor of Shreve’s slavering over the sexually charged Sutpen saga, and the homoerotic overtones of coupling Shreve and Quentin around a northern-southern axis:

Columbo went to the Queen of Spain

And asked for ships and cargo.

He said he’d kiss the royal ass

If he didn’t bring back Chicago.

Columbo had a first mate,

He loved him like a brother,

And every night they went to bed

And buggered one another.

Who is to say what impact this properly bred and yet randy Bostonian behaving with his pants down, so to speak, had on Faulkner? Here, in New Orleans, a member of New England’s founding Puritan class consorted with a Creole, mixed-race culture and would later campaign as a champion of American Indian rights, appearing on television opposing legislation that might deprive Native Americans of their ancestral land. His Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Laughing Boy (1929), reflected a literary sensibility that put him in league with William Faulkner.

La Farge’s anthropological sensibility became part of the ethos that suffuses Faulkner’s Indian stories. At parties La Farge, sporting an Indian headband, dramatized his research and entertained the company by doing an eagle dance on a table. That dance, almost universal among North American Indians, portrays, as one source puts it, the life cycle of the eagle from birth to death, showing how it learns to walk and eventually to hunt and feed itself and its family.

There is usually a chorus of male dancers, often wearing feathered war bonnets, who provide a singing and drumming accompaniment, and two central dancers who are dressed to resemble a male and a female eagle, with yellow paint on their lower legs, white on their upper legs, and dark blue bodies. Short white feathers are attached to their chests, which are also painted yellow, and they often wear wig-like caps with white feathers and a projecting yellow beak. Bands of eagle feathers run the length of their arms, and they imitate the movements of the eagle with turning, flapping, and swaying motions.

How much of the dance La Farge enacted, and what Faulkner made of it, cannot be recovered, but without question La Farge brought the immediate and palpable impact of indigenous America to the table.

Photographs of the bespectacled La Farge could easily be used as illustrations for the myopic Shreve. Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles includes a satiric quasi-anthropological caption for Spratling’s caricature: “Oliver LaFarge of Harvard, a kind of school near Boston.” Spratling thought Faulkner’s words showed his “lack of respect for Yankee culture.” Perhaps, but La Farge himself would not have been offended. He reveled in the glory of a fresh start and that, in New Orleans, “Harvard was nothing” to his friends.

At any rate, Faulkner seemed fond of Harvard graduates. He could hear plenty about Harvard from Harold Levy (1915), another Harvard alumnus, who collaborated with Faulkner on a sonnet, and from John Dos Passos, one of Levy’s friends, when they dined at Victor’s. Spratling also remembers Dos and Bill dining every night at Tuchi’s, “a grandiose Italian joint in the French Quarter, where Tuchi and his wife gave resounding interpretations of arias from Pagliacciand other Italian operas. . . . At that time, we all considered him [Dos Passos] one of the top guys, certainly better than Hemingway was at that particular date.”

Like Faulkner, Dos was “a little shy,” but with Faulkner and Spratling, he “talked endlessly and also drank.” Dos Passos, Harvard 1916, wore thick glasses and, like Faulkner, had a gift for the graphic arts. Three Soldiers (1921), like Soldiers’ Pay, Faulkner’s first published novel, is not about the war itself but its impact on the men who are trained to fight it. Like Faulkner, Dos Passos had an “artist’s eye,” as one of his biographers puts it. Dos and Bill rambled down “streets and streets of scaling crumbling houses with broad wrought iron verandas painted in Caribbean blues and greens.”

They reveled in this tropical city, redolent with the smells of vegetation and molasses produced in sugar refineries, and rife with the characters who populate Faulkner’s New Orleans sketches and whom Dos Passos also noticed: “old geezers in decrepit frock coats, . . . [t]all negresses with green and magenta bandanas on their heads, . . . [a]nd whores and racingmen and South Americans and Central Americans in all colors and shapes.” Both men found the city conducive to writing. Faulkner would have added, as he does in Mosquitoes: “About them, streets: narrow, shallow canyons of shadow rich with decay and laced with delicate ironwork, scarcely seen.”

Faulkner, in many ways a loner, nevertheless discovered in New Orleans, in the experience of rooming and crewing with several men, his Ishmael’s tale.Harold Levy, a Jew; Dos Passos, part-Portuguese; and La Farge, lapsed Puritan, contributed to the multicultural making of Absalom, Absalom!, parts of which center on New Orleans as the amalgamation of different cultures, which shaped one another into a kind of mutuality. Newcomers like Faulkner “did not color” the French Quarter. On the contrary, the Quarter “colored them.” The novel includes five mentions of Shreve’s moon-shaped spectacles, and one reference to his working on the figures of Judith Sutpen and Charles Bon, figures of the past he treats like an anthropologist and an artist: a “meddling guy with ten-power spectacles came and dug them up and strained, warped and kneaded them,” making them his creation.

Like La Farge, Shreve goes native and takes over Quentin’s story, fully immersing himself in the lives of the indigenous inhabitants of his research. What brings Quentin and Shreve together, in the greatest novel ever written about dorm-room bonding, is, in part, their displacement from their homelands, an uprooting that forces them back upon themselves in a form of brotherhood. Faulkner, in many ways a loner, nevertheless discovered in New Orleans, in the experience of rooming and crewing with several men, his Ishmael’s tale.

Raffish Sherwood Anderson also came to New Orleans looking for an unbordered America that crossed racial lines and ethnic boundaries. To an old-school New Orleans stalwart like Lillian Friend Marcus, one of the managers of the Double Dealer, and the sister of Julius Weis Friend, one of the magazine’s founders, Anderson seemed “sweet, simple, and overflowing with the joy of life. He was very nice then—I remember the first time he had ever danced—we all went to a night spot and as everyone else was dancing, Sherwood couldn’t resist—well he was exactly like a nice brown little bear—if you have ever seen a bear perform. His tweed suit, his too, too gaudy scarfs which he used instead of neckties and so on—his long hair that always looked as though it needed washing, but just a grand person to be with.”

Anderson presided at the head of what might be called the Algonquin Round Table South. Faulkner first met him in the fall of 1924, shortly after he resigned as Ole Miss postmaster. On a visit to Elizabeth Prall Anderson, Faulkner and Anderson “talked and we liked one another from the start.” These two short men, sensitive and brooding, also had a flamboyant side that expressed itself in various kinds of costumery. Faulkner remembered Anderson’s “bright blue racetrack shirt and vermilion-mottled Bohemian Windsor tie.”

Anderson, a veteran of the Spanish-American War, had 20 years on Faulkner and a fund of stories about knocking around raffish resorts, especially whorehouses. Anderson, a down-home sort of man, had grown up in his father’s livery stable. He was “solid, not ‘arty.’” But he was also sensitive, writing about those “grotesques” in Winesburg, Ohio, characters deserving of empathy and respect for their plight in a small town that did not value and sometimes scorned their failings and eccentricities in a sort of community intolerance familiar to Faulkner. What Faulkner said about Anderson might be applied to himself: “I think that he maybe would like to have been more imposing-looking.”

In his memoirs, Anderson presented Faulkner as a character out of a history book—like Abraham Lincoln meeting Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy, a small man in a “huge overcoat.” Lincoln said to a friend, “Did you ever see so much shuck for so little nubbin?” Faulkner showed up at Anderson’s Pontalba apartment in a bulky big overcoat. “I thought he must be in some queer way deformed,” Anderson recollected. Faulkner was looking for an apartment and asked if he could leave some things, which turned out to be “some six or eight half gallon jars of moon liquor” stuffed into the big coat.

Faulkner did not immediately take up residence in New Orleans. Elizabeth Prall Anderson recalled that he showed up again—this time in early January with Phil Stone, who spent a week in the city. With Anderson then on a lecture tour, the visitors spent an “uproarious week” with Elizabeth, taking their meals with her but living in a “funny little hotel [The Lafayette] with rickety rooms that opened into a ramshackle courtyard.” They liked to go to bistros and to movie theaters frequented by “colored people,” as they were called then.

__________________________________

Reprinted from The Life of William Faulkner, Vol. 1 by Carl Rollyson by permission of the University of Virginia Press. Copyright © 2020.