Captain Jazmín Caldera, native of Zarzales, Extremadura, couldn’t eat the turkey broth with flowers, though it looked exquisite and he was starving. He had been assigned a place at the table between the priests of Xipe and Tezcatlipoca. Draped like a cape around the shoulders of the former was the decaying, blackened skin of a warrior sacrificed who knows when, while the latter’s matted locks, neither cut nor washed since he’d taken orders at the temple, were crusted with many moons of sacrificial blood: quail daily, sometimes turtle or wolf, but on major festival days—of which there was one each month—warrior blood, preferably Tlaxcalteca. Jazmín Caldera reached out his hand for the fine lacquered cup, into which a woman had poured chocolate frothed in water with honey, chile, and vanilla, and breathed in the scent as deeply as he could, trying to ignore the wolfish aroma exuded by his dining companions. He looked up toward the head of the table. The captain general of the expedition was watching him fixedly, those icy eyes ordering Jazmín to be quiet and eat his soup once and for all. Caldera turned his gaze to the left. The priest of Xipe was painted from head to toe with black and blue stripes. Under the human skin he wore as a cape, he had on a white robe patterned with shoots of corn in a featherwork design. Two enormous jade disks hung from his ears, set around the edges with gold and silver snakes. They must have been hideously heavy, surely painful. Under his lip was a gold labret: a little dog’s head. It slipped in and out of sight each time he took a swallow of soup or chocolate, as if playing in a little skin house.

The priest of Tezcatlipoca was dressed less luxuriously, in a plain red robe. His body, or what could be seen of it, was painted black, except for the part of his face between nose and chin, which was also red. The ribbon that tied up the towering, malodorous thatch on top of his head could have graced the swanlike neck of the daughter of a Spanish grandee: freshwater pearls, little jade heads, and coral animals chasing each other along a trail of silver thread. His teeth were filed sharp as a cat’s.

Jazmín returned his attention to his plate, to his cup of chocolate, and then again to the captain with his unrelenting stare, seated at the head of the table elbow‑to‑elbow with Princess Atotoxtli. Now the captain raised his eyebrows to punctuate the urgency of his command: Eat! Caldera lifted the cup of chocolate and took a long swallow. Though the drink was possibly his favorite of all the many extraordinary new things he had tried since they had landed, it nearly came back up. It was impossible to dissociate it from his tablemates’ reek of coagulated blood.

Even so, the immediate thrill of the cacao, to which the new arrivals were as yet unaccustomed—a tickle at the base of the neck, a shudder of the spine, the tremendous urge to do something, anything—made him suspect that he could handle the soup despite the stench. He picked up the dish, and as he raised it to his mouth, he felt spasms again. He set it down. Now the princess was watching him curiously too.

Jazmín raised his eyes, looking everywhere but toward the priests and the captain general. He gazed directly across the table, past the heads of Aguilar and Malinalli, people he assumed were used to eating even human flesh. He looked at the wall and thought about the city of Selenites swelling on the other side. He returned in his imagination to its temples, canals, and floating neighborhoods ringed by giant rectangular rafts, each identical to the next in shape and size, where the Mexica grew their vegetables and flowers. He remembered his spiritual exercises at the Jesuit school in Trujillo, and in his mind’s eye he saw the lake that surrounded the city, preventing the Spaniards from escape if the emperor gave the order to loose his eagle warriors; he envisioned the volcanoes that had been such torture to cross, standing sentry over the Anahuac Valley, scattered with white cities and fortified with towers and temples. Again he saw Amecameca, the start of the Iztapalapa causeway across the lake, the flower arch, mythical Moctezuma and his retinue, and the moment when the idiot captain general almost sank everything by trying to hug him. They had entered the city; the mayor had lodged them in Axayacatl’s palace, so lovely and serene; and they’d been invited to eat right here, in the hall of emperors past, with the princess’s entourage. They had come to the very heart of the great, invincible city of Mehxicoh‑Tenoxtitlan, and their task was almost complete.

Everything was a little hazy, muddled. All of it an honor perhaps undeserved. They had made it here with staggering effort and lunatic determination, and they had proved themselves to be good soldiers, going on when no one else would have, always betting against the odds. It meant something. But that had been the road, the hustle, a game—played to the death, but a game in the end. Now that they were in the palace and in the presence of the princess, it seemed to Jazmín that the ship might start to take on water anywhere. The captain general—sitting amid such grandeur, such saturnalian figures—suddenly looked like what he’d been back in Cuba: an ill‑favored and artless son of Extremadura. They were provincials, nobodies, hicks. One blunder could reveal that they were really a bunch of loudmouth bastards who claimed to have come in the name of an emperor they never had a hope of meeting, when in truth they didn’t even represent the adelantado of Cuba, to whom they’d given the slip in order to do what they were doing. Jazmín sighed. He returned his gaze to the table, but couldn’t bring himself to take his plate in his hands. In the calmest of voices, friendly as if he were commenting on the pleasing warmth of the Anahuac sun, he said that they would have to forgive him, but nobody could eat like this.

The captain general smiled slightly, tilting his head. He moved his jaw back and forth a few times. Each time he jutted out his chin, his eyes narrowed a little: a ghastly sight. Jazmín nodded his own head discreetly as if pleading for his superior’s patience, but really he only wanted the man to stop making that nightmarish face. He picked up the soup plate again in both hands, breathing deeply to lock in its scent, and again the smell of dried blood and decaying skin got in the way. Lowering the plate, he set his palms on the linen tablecloth and closed his eyes. He kept his composure. Controlling his nausea and tone of voice, he glanced right and left at the priests. I mean, what is this? he asked. And he smiled at the captain general as if begging for pity.

Cortés took a generous swallow of soup and bellowed his delight. He smiled at Princess Atotoxtli, seated next to him. With a pleasant expression still on his face but with his fists clenched on the linen cloth—his knuckles white with rage at Caldera’s insubordination—he said quietly, almost in a singsong: Shut up and eat the soup, son of a bitch; we are the empress’s guests. Caldera smiled. I can’t, he replied; if only you knew what they smelled like, Hernán, this one here must have eaten mashed‑up babies for breakfast. The captain general returned his smile and, as if commenting on the sweetness of the chocolate, said: You think you smell of roses? Shut up and eat, then vomit later all you want. Malinalli, the Nahua translator, raised her eyes from her plate. In Maya, she asked Aguilar, the Spanish translator, whether they should translate what Caldera and Cortés were saying for the benefit of the princess and the nobles and priests crowded around the table. He whispered in her ear, also in Maya, that he didn’t think so, it was just conquistador chatter.

Malinalli spoke Nahuatl and Maya, but not Spanish. And Aguilar spoke Maya and Castilian, but not Nahuatl. The conversations between the Colhua and the people she and everybody else called the Caxtilteca still had to pass through a double filter. Now she felt the punch of Princess Atotoxtli’s gaze—the princess was the emperor’s sister but also his wife—waiting for her to translate what had been said. She lifted her face, smiled, and said in Nahuatl: They are saying how delicious everything is. The princess twitched her mouth as if to suggest she didn’t believe a word of it. The translator shrugged. In a bid for patience she said: They are savages, of course; they like the taste of the juice of rotting fruit they bring from their own lands, so they can’t believe there is such a thing as chocolate.

The priest of Xipe, who had just annihilated his soup, burped modestly and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand, smearing his makeup a little. He said in Nahuatl, as if talking to himself: They’re imbeciles and they smell like dogs and caca; I say we sacrifice them now before we get used to them. The princess gave him a reproving look. We’ll do what my brother tells us to do, she said firmly. Aguilar cleared his throat to get Malinalli’s attention. He asked her in Maya what they were saying. She replied: The priest is asking the princess whether she likes Hernando’s looks; she says she finds him handsome but such things are hardly fit conversation for a queen. Aguilar raised his cup of chocolate. With a glance at his comrades, he said: Looking good, Spain. He turned his gaze to Jazmín, over whom he had particular sway, and said: And you, eat the fucking soup, because they won’t serve the next course until you finish, and we’re all hungry. Caldera considered how hard they’d fought to get where they were, and he managed to put things in perspective. He finished the soup in a single gulp. Salud, said the captain general, raising his own glass.

__________________________________

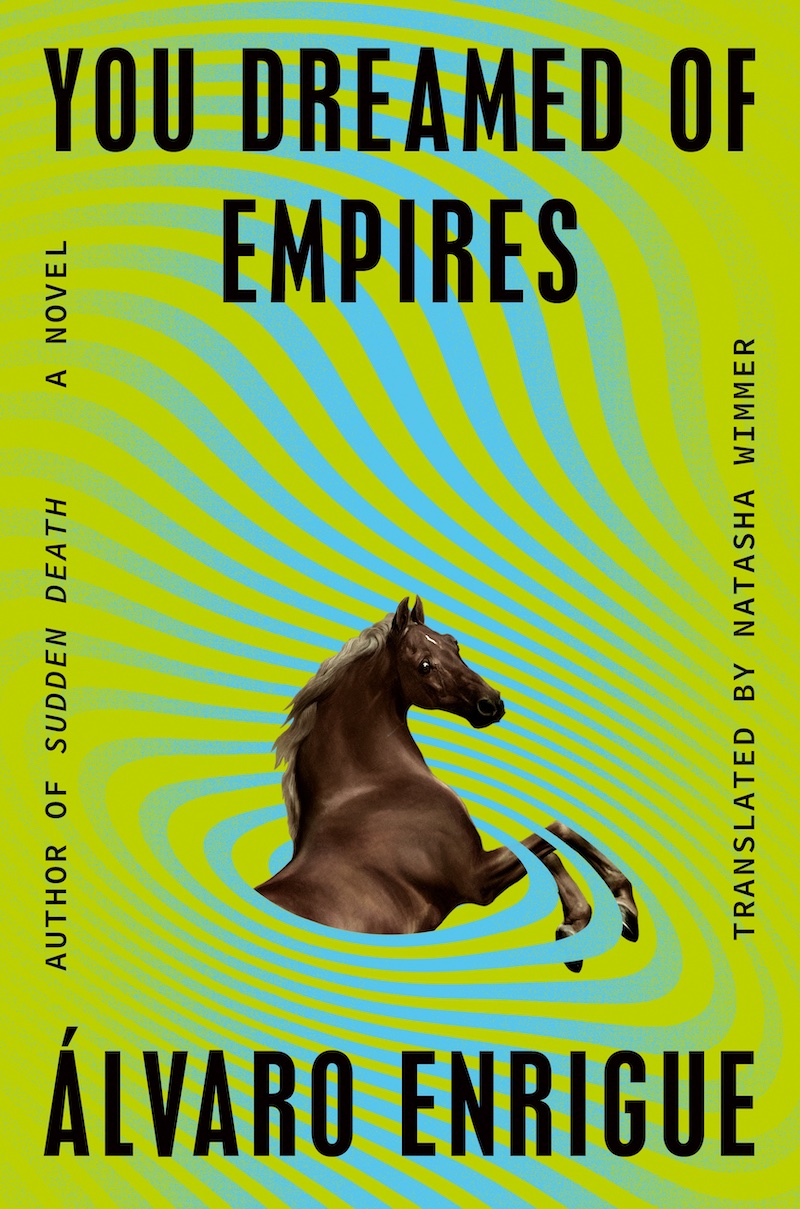

From You Dreamed of Empires by Álvaro Enrigue, translated by Natasha Wimmer. Used with permission of the publisher, Riverhead Books. Copyright © 2024 by Álvaro Enrigue/Natasha Wimmer.