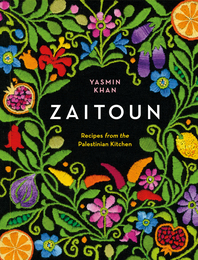

“You Can’t Discuss Palestinian Food Without Talking About the Occupation.”

Yasmin Khan on the Joys of Palestinian Cuisine

On my first morning in Jerusalem, I woke up early and headed straight to the rooftop of my hotel, nestled in the heart of the walled old city. The sun had just begun its slow ascent through the sky and, as I sipped my cardamom-spiked coffee, I gazed out upon the densely concentrated assortment of houses and apartments, interspersed with religious sites and historical buildings. My eyes paused, just for a moment, on the golden sphere of the Dome of the Rock, glistening in the middle distance.

As I waited for my breakfast—the Palestinian staple of hummus, flatbread, sliced tomatoes and olives—I was captivated by the glimpses of ordinary life revealed from where I was sitting. The mothers carrying baskets of wet clothes to their roofs to hang on the washing line; the stray cats running in and out of hidden corners; the clatter of market vendors setting up their stalls; the heady scent of za’atar beginning to rise through the air.

The old city of Jerusalem represents the beating heart of the Palestinian community and bursts with life and vibrancy. The city’s walls and gates in their current formation were built in the 16th century during Ottoman rule, and today it is split into four distinct quarters: Arab, Jewish, Christian and Armenian. The main entrance for the Arab quarter is Damascus Gate and, upon entering, I paused in the doorway under the watchful eyes of the teenage Israeli soldiers who police the area, and bought a large bunch of sage from the Palestinian women who crouch on the floor at makeshift stalls.

I wanted it to flavor small cups of black tea, a new, welcome discovery for me—an ardent tea drinker—but common in Palestine.

Entering the cobbled streets of the walled city, I headed straight for the glorious assortment of seasonal fruits on display and grabbed a few favorites—pomegranates, figs and peaches—to snack on later. Tourists were beginning to throng through the small passages of the souk, which sells everything from freshly baked bread and sweet flaky pastries to vegetables, meat and dairy and household goods such as ceramics, clothes and textiles. The old city is the kind of place a hungry traveler can relish getting lost in; simply follow your nose down winding streets to spice sellers, exquisite kebab makers and moreish halva confectioners.

Raya Manaa’ © 2018

Raya Manaa’ © 2018

After spending the morning walking through the narrow passageways, sampling as many crunchy sesame and fennel ka’ak biscuits as is decently permissible, I made my way out of the walled gates and walked deeper into East Jerusalem to meet Essa Grayeb, a Palestinian rheumatology nurse, for lunch. We met in the courtyard of the Zahra Hotel, a dark, crumbling building that has seen better days. But we came for the food, not the décor, and Essa ordered kefte bil tahini, a sumptuous dish of spiced lamb meatballs baked over thin slices of potatoes, then smothered in a garlicky warm tahini sauce.

“Jerusalem can seem very charming to tourists,” Essa said, as he cut through his kefte and delicately dipped it in the tahini. “But actually, it’s a really tough place to live. It feels like a pressure cooker. It is a divided city and you can’t take it out of that context. If you live in Haifa you might not see the Occupation, but here, we exist with it every day.”

In the original UN partition plan for Palestine in 1947, Jerusalem was given to international administration, but what followed was a bloody war that led to a divided city, with the Israeli population settling in the West and the Palestinian population in the East. In 1967, the Israeli army captured the Old City and, along with the rest of East Jerusalem, annexed it as Israeli territory. Today the Israeli government continues to control East Jerusalem, which it considers part of its national capital. Palestinians, the United Nations Security Council and the international community at large, however, see East Jerusalem as part of the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

“I think that, just dealing with the cuisine, you will see a romantic view of Jerusalem life,” Essa continued. “But that doesn’t reflect our reality.” Essa wasn’t the first Palestinian to challenge me on writing about food culture in a region fraught with conflict. Over the last 70 years, Palestine and its citizens have been over-researched and over-interviewed by journalists, NGO workers, UN officials and elected representatives alike, and there run deep feelings of frustration at so many people documenting their situation while so little changes. One frustrated woman angrily told me: “We are not clowns in a circus for you to come and watch and make research notes about and then make your name from writing down our suffering.” It was a comment that touched me deeply.

“I understand that you want to share our culture,” Essa continued, politely but pointedly. “But you can’t discuss Palestinian food without talking about the Occupation. About the water restrictions, about the inability to move freely, about the checkpoints, about the house demolitions. This isn’t me being political, this is me explaining that the Occupation affects how we eat. You can’t escape it.”

It was a conversation I continued the next day with singer Reem Talhami, who echoed Essa’s sentiments. “From the very beginning, Jerusalem is heavy,” she told me, inhaling deeply on her cigarette. “The moment you get into the city, you feel it in the air.”

Tall, striking and beautiful, Reem embodies Palestinian passion and has the remarkable gift of being able to translate it into song.

We met at her house to make fattoush, a Palestinian staple and one of my all-time favorite dishes of the region, a sharp and tangy salad of crisp lettuce, juicy tomatoes, crunchy cucumbers, chopped parsley and mint, flecked with toasted shards of bread. Fattoush is exactly the kind of food I want to eat on a hot summer’s day, refreshing and uplifting all at once. It is a dish that has the ability to instantly lift the mood, with its enlivening dressing made from extra virgin olive oil, lemon juice and sumac, an astringent, citrusy and vibrant seasoning made from the ground berries of the native sumac bush.

Raya Manaa’ © 2018

Raya Manaa’ © 2018

As we chopped and sliced the vegetables, Reem talked about her work as a singer.

“I wanted to use my voice to share the story of Palestinians,” Reem told me. “To tell our side through the song, to help uplift my people. This has been my mission.” She handed me a large bunch of parsley and I began to strip away its coarse stems and transfer the leaves to a chopping board for slicing.

“But it’s hard in Jerusalem,” she continued, scraping chunks of cucumber off the wooden board and into a large terracotta serving bowl. “It’s a city that you love and hate at the same time. I am raising three daughters here and there are lots of challenges for girls in a city that is becoming increasingly religious. My daughters are full of talents—they dance, sing and act—but the lack of freedom of movement with the checkpoints is very hard. If my daughter is accepted into Birzeit University (in the West Bank), then traveling from there to Jerusalem every day is too hard. She will have to endure so many hours on the road and go through all of that humiliation at the checkpoints.”

Reem grabbed a tall, dark bottle of extra virgin olive oil from the cupboard and started assembling ingredients for the dressing. “How does it feel for you?” I asked. “Going through these checkpoints?” Reem sighed and paused for a moment, putting the bottle down. “It depends on how the soldier feels. We have lived with the soldiers for many years now, I’ve been meeting them at checkpoints in my teens, my twenties, my thirties. I met them as a child, a young woman, a wife, a mother. I’ve grown up with them. Sometimes the soldier is human, sometimes he’s a monster, sometimes he’s a sort of god dictating your day. Sometimes he’s just a little boy who doesn’t want to be there, who just wants to be at the beach with his girlfriend, having a swim or sharing a kiss.” We went back to our chopping for a while, in silence.

“Sometimes the soldiers cry, sometimes they shoot their guns, sometimes they kill. Psychologically, the unpredictability of the Occupation is what makes you feel so insecure . . . your day is not in your hands.

“For millions of people around the world, Jerusalem is some mythological, magical place. But for me, it’s not that, it’s not something that is at all sentimental, it’s my daily life. And the people who live here are having a really hard time under all the pressure. That’s why they lose hope and do crazy things.”

Out of all the places I’d traveled in Israel and the West Bank, Jerusalem undoubtedly felt the most challenging. So it was heartening to spend an evening cooking with Jamal Juma’, a community activist who is decidedly upbeat. Jamal is the co-ordinator of Stop the Wall, an umbrella group of organizations who campaign against Israel’s Separation Wall, which is being constructed around the West Bank.

Raya Manaa’ © 2018

Raya Manaa’ © 2018

The Wall (which has been deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice) cuts through villages and farmland, separating families from each other and communities from essential educational and medical services. Despite the ICJ ruling, the Wall continues to be built and is now more than 60 percent complete. If finished, it is set to measure more than 430 miles/700km, the distance between London and Zurich and four times as long as the Berlin Wall. While the Israeli government claims its purpose is to provide security, the route of the Wall encircles 80 Israeli settlements, suggesting that its primary function is to incorporate these communities into Israel. Jamal, along with many of his colleagues at Stop the Wall, have been arrested, detained and imprisoned without charge by the Israeli authorities for their campaigning.

Despite working on such a challenging issue, Jamal is someone who makes you feel unshakeably positive about the world.

A native Jerusalemite, the recipe he showed me how to cook has its roots in the Negev and is a celebratory dish served at feasts or on special occasions. Called mansaf, it’s a rich and creamy stew of lamb slow-cooked in jameed (a type of fermented whey made from ewe’s or goat’s milk) and served on top of bread and rice. As we stirred the jameed into hot water to dissolve it, Jamal cracked jokes about the lack of inspiring leadership within the Palestinian Authority and teased me about the role of the British in creating the situation, when they gave up their mandate in Palestine in 1948.

“How can you stay so upbeat,” I asked, “given the situation you see here every day?”

Jamal smiled and reached for the lamb pieces that we had trimmed of fat, gently placing chunks of them in the hot broth, one at a time. “It’s easy,” he said. “I stay hopeful because I believe that apartheid will eventually be defeated. Because history tells us it is not the norm. I don’t believe, in the 21st century, we need to lock people inside walls in order to get some false sense of security and I know, in my heart, that building walls is not a sign of strength but a sign of weakness.”

He dropped the final piece of lamb into the pot, reduced the heat so the stew could cook on a gentle simmer, and firmly placed the lid on. “Remember Yasmin,” he said, turning to face me, “walls don’t last forever.”

__________________________________

From Zaitoun: Recipes from the Palestinian Kitchen. Used with the permission of W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2019 by Yasmin Khan.