You Can’t Choose Your Influences: On the Unexpected Book That Made Me a Writer

Matt Rowland Hill on the Intersection of Spiritual and Literary Canons

I once believed influence was largely a matter of choice, as though your task as an author was to enlist a little family of writers to support you as you worked. While writing my first book I even put this idea into practice quite literally: I put a shelf above my writing desk, filling it with the 30 or 40 works from which I hoped to siphon the most influence as I worked. I know precisely which titles they were because I’m looking at them now.

If I wanted inspiration to write gorgeous prose, I’d reach for Hollinghurt or Cusk; my go-to for imagery was either Nabokov or Denis Johnson; for character, Adichie or Franzen; for dialogue, Rooney or Zadie Smith. Mary Karr’s The Liar’s Club possessed not so much a technique I coveted but a personality trait I intended, frankly, to plagiarize: a way of writing about a fucked up family with unflinching honesty and unfailing love at once. And some monoliths of the canon—Middlemarch, American Pastoral—were there for the many days when I couldn’t recall the point of writing a book, or why literature mattered at all.

The shelf was, it turned out, one of my better ideas. When I wrote at home, I tended to use it several times a day. So were those books my major influences? Only (I now see) in the most trivial of senses. Perhaps you’ve already noticed the confusion inherent in my earlier image for how influence was supposed to work: a “little family” of writers you “enlist”. But, of course, you don’t enlist your family—you inherit it, for good and ill. And just as I may wish to be influenced by my friend Jasleen’s preternatural kindness and my friend James’s voracious intellectual curiosity, the truth is my character was fundamentally shaped long ago by influences in my childhood I was too young to be conscious of. And I’m closer nowadays to a final edit than a first draft.

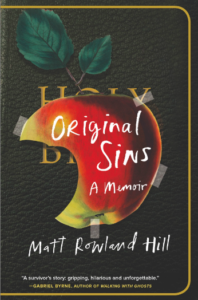

It’s the same with writing. With a quarter of my memoir Original Sins to go, I saw that the book that most influenced me—indisputably and by far—wasn’t on the shelf above my desk. In fact, I hadn’t really read it for some 20 years, and I often wished I never had. I couldn’t even say it was a book I particularly liked. And yet there it was, staring back at me from my own words:

It’s been well over a decade since I put away childish things and turned my back on my parents’ dogma. […] I had an overdose of the opiate of the masses and decided I preferred the real thing. I shook the dust off my feet at eighteen and tried to forget my childhood faith…

Even this description of walking away from my parents’ faith enacts a linguistic homecoming, by quoting the very scriptures my younger self rejected: 1 Corinthians 13:11 (“put away childish things”) and Matt 10:14 (“shake off the dust of your feet”). There were similar examples on virtually every page of my book. Sometimes I deliberately profaned or subverted a verse, like when I made Matthew 16:26 an argument for atheism: “what would it profit you if, in attempting to win your soul, you lost the whole world?”

But often I simply found biblical imagery coming to me uninvited, and I threaded it into my sentences, borrowing its resonance and poetry. Jesus’s dictum about the impossibility of one man serving two masters aptly summarized the monomania of the addict as drugs slowly took precedence over everything else. When I came to describe my younger self’s chronic deficit of insight and intuition, Matthew 13 came to mind: ‘I hadn’t had eyes to see or ears to hear.’ At a rough estimate, the book probably contains between 100 and 200 references to the Bible. I’d had no idea how much of it I recalled.

I had been raised with the belief that a passionate relationship with the written word could form a crucial part of an individual’s life.

When I first realized how deeply influenced by the Bible I’d been, I was dismayed. My scriptural recall seemed to prove the failure of all my efforts to remake myself. I had spent my entire adult life struggling bitterly to undo my deep religious wiring and to erase all memory of the devout believer I once was. When I was a junkie, often on the verge of death, I used to console myself without a trace of irony that it could be worse: at least I was no longer an evangelical Christian.

I’d long believed my years of immersion in literature—with its intrinsic principles of skepticism, tolerance and nuance—had inoculated me against the values that defined my parents’ Bible: dogma, prejudice, dualism. But what if I’d failed to purge my thinking of evangelicalism’s mad binaries and toxic reductions—heaven/hell, good/evil, salvation/damnation— any more than I’d failed to purge scripture from memory. What if, after all, evangelicalism lived on in me like some demonic possession?

I’d always believed I’d had a childhood virtually devoid of literature—another fact I of course counted against my parents. Almost uniquely among writers, I couldn’t recall a single book I’d loved as a child. If only I’d had a family where books were a birthright, like the kids from well-read, well-bred west London homes I’d met at university. Meanwhile, to become a reader I’d had to fight almost to the death—because to become a reader in any serious sense meant rejecting my parents’ whole system of reality, and ultimately rupturing our relationship irreparably. Perhaps that’s why books had meant nothing to me until, at 13, I found Kafka—and suddenly they meant everything.

But after my initial dismay, as I saw the evidence of the Bible’s influence staring back at me from almost every page of my book, I began to revise the story about my childhood I’d clung to for so long. Now it was obvious that, unorthodox though it undoubtedly had been, my upbringing had been intensely literary. It wasn’t just that the King James Bible and the English hymn tradition—including Watts, Wesley and Cowper—were my mother’s milk, which meant I was intimately familiar with the vocabulary and syntax of 17th and 18th century English prose and verse.

Far more importantly, I had been raised with the belief that a passionate relationship with the written word could form a crucial part of an individual’s life. I’d spent so long envying those book-lined west London townhouses of my university colleagues, I’d failed to recall that—in contrast to a number of them—I’d never been taught to see books as markers of cultural sophistication, or mere signs of erudition and taste, or simple accoutrements of a bourgeois lifestyle.

To this day I have an almost worshipful attitude towards great literature. What other people call spiritual experiences are, I’m certain, the kind of strangely transporting moments literature occasionally helps me access.

Rather, I’d been raised with the notion that books—or, rather, the Book—contained the answers to life’s most urgent questions, and were repositories of everything meaningful and good. Reading could be as thrilling as anything else in life—one way of encountering the Holy Spirit—but it was never merely a means of entertainment or escapism. Even to call reading a matter of life and death would be a gross understatement, because its role in determining our eternal destiny made it much more serious than that.

Up until the age of 18, I read or heard the Bible read aloud almost every day. When after a long struggle I realized my faith had vanished into thin air, I quickly transferred my reverence for the scriptural canon to the literary canon. And even as I’ve come to take the opposite view to my parents on virtually every important question, in this respect their influence on me went far deeper and was more consequential than it had ever been when it was confined to dictating my beliefs. To this day I have an almost worshipful attitude towards great literature. What other people call spiritual experiences are, I’m certain, the kind of strangely transporting moments literature occasionally helps me access. I still view reading as central to my concept of a good life, and a life without books would not, to me, be one worth living.

I now write with two shelves above my desk. There’s the original one, which comprises all the books from which I aspire to extract influence. And I like to imagine there’s an invisible one too, where I store all the writing that shaped me as a person and as a writer before I even knew what was happening.

And these days I keep a Bible on both shelves.

__________________________________

Original Sins: A Memoir by Matt Rowland Hill is available now via Hanover Square Press.

Matt Rowland Hill

Matt Rowland Hill was born in 1984 in Pontypridd, South Wales, and grew up in Wales and England. His writing has appeared in the Guardian, the Independent, New Statesman, the Telegraph and other outlets. He now lives in London. Original Sins is his first book.