You Cannot Protect Your Children From Moana: How Not to Fight Fairy Tales

Julia Langbein Channeled Her Parental Anxiety into Better Girlhood Characters

I am not the best mom. I found an old shopping list recently that looked like this:

Oysters

Wine

Dinner for kids?

You can’t write books without being selfish, and I’m a little bit selfish. But I always imagined, when the time came to do battle on my daughters’ behalf with mass culture, with simplistic, gendered storytelling, that’s when I would shine.That’s when my special skills would suddenly be called upon.

I have a PhD from the University of Chicago! I’ve talked in bare rooms for hours with gamey geniuses about the colonialism and sexism naturalized by modern media. I’ve done Marx and Manet. Surely, I thought, I can protect my daughters from Moana.

Turns out I absolutely cannot protect them from Moana. Turns out Moana wins every time, because Moana is the least of my problems. The problem is me.

I used to imagine my household of little girls full of gender-neutral things, hammers and burlap and firefighter suits. Instead, I buy them nonstop princess dresses like I’m trying to betrothe them to a Hapsburg. They love it, they feel beautiful, and magical, and I remember feeling that way in my grandma’s dress-up box. It’s no distant memory, that feeling—I still long for it, and every retailer knows it.

Here’s a sad fairytale: One recent bleak winter’s day I bought a pair of comically expensive pants, even though the smart math says I should wear sweat-wicking leggings every day til I die. But I put these pants on in the fitting room and they made me look like my name was Vanessica and I kissed different people every night. I play dress-up at home in these pants that are made in Italy and are cut so beautifully that they change the whole way I move. Change: the pants promised a change, and even though they cost a stupid amount of money I was scared to walk away from them because everything would be the same, and known, and I want an unknown in my future.

On the day I wear them, something will happen. I’ve planted a plot point, I’ve put an exotic bulb in the vegetable garden. I’ve reached out from the predictability of my life and pulled in a piece of fabric from the capricious classes, the callous classes, the drunk, the fun, the mean, the libertine classes— the princesses. I believe. Cut to Jiminy Cricket singing: “When you wish on luxuryyyy, there’s no telling who you’ll beeeee.”

They are tiny-waisted and fashionable, and her parents are robotic but still porn-star hot, something a toaster might masturbate to.Desire, that’s where they get you. The intellect has no power in the world of big, glossy stories. I thought I could say to my kids, “Sleeping Beauty (1969) creates an active / passive, male/ female binary, you see?” and all the while I could keep secret how much I love the drawn lines in motion, her silhouette, the prince’s shoulders when he dips as they dance. But they love it, too. There’s a kind of desire built into the sheer sensory overload of animation. My daughters can spend hours watching Miraculous: The Adventures of Cat Noir and Lady Bug (2015-ongoing)—I’ll spare you the premise, the title is complicated enough.

But in every episode the main character, a teenage girl, undergoes a quasi-orgasmic transformation into a superhero. There is a close-up on her shiny elastic butt (“girl power” excuses a lot) as she explodes into a soaring, bone-thin bright-red warrior, her skin a tactile chain-mail in MAC Russian Red. Meanwhile I’m standing there with tangled hair holding piles of brown cardboard like a canapé-tray of dog food going, “Hey want to do a puzzle?” Desire is in the very surfaces, or not.

When I was little I loved the plastic world of 1980s unreconstructed materialistic Barbie, I ran my fingers over her pink car and her smooth boobs, chaste but still somehow full of an awesome milk. Thirty years later, Barbie’s Dreamhouse Adventures (2018-2020) is my older daughter’s favorite show, because the dialogue is zippy and computer-generated Malibu is a place you want to be (if you’re a Republican who likes bright colors, which most children are.)

Barbie and her friends solve problems! For example, they once found their way out of an escape room that they’d paid to enter, so that was impressive. They are tiny-waisted and fashionable, and her parents are robotic but still porn-star hot, something a toaster might masturbate to. This is all fine, sunny American world-building.

The dark twist is that every episode is narratively framed as Barbie’s own production for her YouTube show. She’s not just a person in the world, she’s self-aware about her social media capital. Are you incredibly sad yet? Don’t you miss the days when she was just a clothes horse, banging a hairless eunuch in a four-story house? Meanwhile, I pretend to “message Daddy about dinner” while I check the likes on my Instagram because like Barbie, there are things I want that I can’t name.

There was a time when my daughter had just begun to watch full-length Disney movies and she did not understand why we did not French kiss each other at bedtime.But Barbie is a chump next to Elsa. Disney’s Frozen is the fourth-highest-earning media franchise in US History, worth nearly $14 billion, and the Disney Princess franchise overall has earned nearly $50 billion— I think I’ve personally contributed about $27 billion. What can I do? They love Frozen, a story about rich white sisters who need a man to help them figure out how to get the heater working again.

Much has been made of the kiss at the end of the film, where Kristoff, an unemployed ice merchant, asks Anna, the princess, for her permission before he lays his lips on hers. Consent! The parents all cheered. This was truly a step up from Sleeping Beauty, which taught us that it’s cool for men to kiss women while they’re stone-cold passed out.

Now our little girls all know that they must consent to the inevitable heterosexual coupling that ends all significant journeys. There was a time when my daughter had just begun to watch full-length Disney movies and she did not understand why we did not French kiss each other at bedtime. When a day ends, like a story, don’t two people have to make out?

Look, there’s plenty of excellent storytelling out there—Bluey and Karma’s World, for starters, which are both deliberate insurrections of sheer thoughtfulness. And there are the valiant countermeasures. I think a lot about Gender Swapped Fairy Tales (Faber, 2020), a book my kids don’t find particularly special or different. They take at face value stories like “Handsome and the Beast,” and “Mistress Puss in Boots,” but can you intuit already in those titles how erotic it is?

We’ve become so inured to the beauty of girls in stories, to the anchoring presence of stable Kings, that when you switch the genders around—all the beautiful, beautiful men in this book, and the powerful Queens—it lays bare how oddly central desire is in fairy tales. In the illustration for “Handsome and the Beast,” the beast, an enormous tigress with horns, sits across a table from slender man dressed like a 1970s gigolo, who smiles, desperate to please her.

“Turn the page, Mommy.”

“You guys don’t want to stare at this a little longer?”

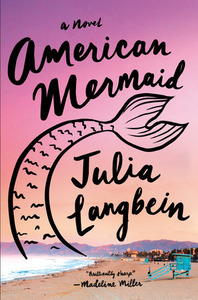

I didn’t write my first novel, American Mermaid, for my kids. Selfishly, I wrote the kind of deeply hilarious book I want to read more of. But I haven’t realized until now that there was an answer to my parental anxieties hidden in my own book—almost miraculously, intuited by an earlier me. American Mermaid is about a writer who creates a female character in a best-selling novel and is lured to LA to turn that novel into a screenplay.

As Hollywood tries to dumb down the mermaid and sex her up—to give her the same old desires—the mermaid exerts her own power in the world, coming to life in ways her author never expected. The things my daughters come up with, when they give me access to their minds, are so much richer and more surreal than any of the three-act conservative fantasies Disney conjures for them—a person named “Nenny” who lives in an airplane, a spider named Susan who wears a winter coat.

There’s a line in American Mermaid where a mermaid who was raised as a human finally gets released back to the sea, and her adopted human mother, who tried so hard to help her live life as a girl says to her, “Go, be more than we know.” Off she goes, bashing things, being selfish.

__________________________________

American Mermaid by Julia Langbein is available now from Doubleday.