You Cannot Go to Your Country: Victoria Amelina on the Start of War in Ukraine

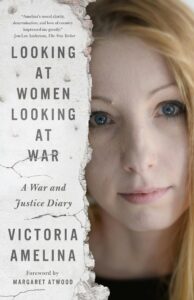

From Her Unfinished Book, “Looking at Women Looking at War”

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Victoria Amelina was writing a novel, taking part in the country’s literary scene, and parenting her son. Now she became someone new: a war crimes researcher and the chronicler of extraordinary women like herself who joined the resistance. On the evening of June 27th, 2023, Amelina and three international writers stopped for dinner in the embattled Donetsk region. When a Russian cruise missile hit the restaurant, Amelina suffered grievous head injuries, and lost consciousness. She died on July 1st. She was thirty-seven.

__________________________________

My February 24

Our flight to Ukraine is scheduled for 7:00 a.m., February 24, 2022. When we take a taxi to the airport, it’s still dark in Egypt. Everyone else in the half-empty seaside hotel seems to be sleeping peacefully, and I decide not to wheel but to carry my suitcase past dark bungalows so that no one is woken up because of me. Or maybe I just want to hear the quietness of the world as if I already know it is about to change forever.

It’s 4:00 a.m. in Egypt and in Ukraine. I look up: the sky’s clear, and the constellation of Ursa Major is shining brightly above our heads. Other constellations do too, but I don’t recognize them. I first saw such a starry sky in Luhansk when I was five. We lived in Lviv back then and there was always too much light pollution to see the stars well enough to learn how to recognize constellations.

In Luhansk, the relatives we visited lived in a house, on a street that was dark enough during the night to see all the stars above. Someone showed me, a five-year-old, Ursa Major back then in Luhansk. Perhaps it was my mom. So the sky full of stars became one of my memories about the city. Stars meant my childhood and Luhansk for me. I grew up, Luhansk was occupied by Russians in 2014, the world changed, but I haven’t learned to recognize any other constellations. And February 24 is not a day to learn about constellations.

I ask my son to hurry up; if we miss our flight, we’ll be stuck in Egypt, beautiful but not easy to navigate for a family that does not speak Arabic.

On the ride through the desert, I’m trying to read the news. The connection is poor again, almost nonexistent. Despite all my efforts, I manage to receive just one message, short, like a World War Two telegram from the front line. It reads: “Explosions in Kyiv.”

I am gasping. This must be a mistake. Many sounds may seem like distant explosions when you are scared. And what if these are just fireworks, someone’s joke? We’ve read too much scary news lately, we looked at the toys in the piles of the broken bricks, not the stars, we thought about all the wrong things and made the wrong wishes. Besides, the explosions could have all kinds of explanations. What if this is a gas explosion? Gas explosions are a possible thing. The bombardment of a European capital is not. Not anymore, I mean. Never again, right?

“Can you see the stars through the window?” I ask my son. “I cannot,” he replies, too sleepy.

“I can see Ursa Major, the Great Bear,” I lie, so he keeps trying to see the constellations despite the glare from my phone’s screen on the window while I try to contact our family and friends in Ukraine. I don’t quite remember who in particular I write and call; I mostly fail anyway. The desert is endless.

“Oh, I see it!” shouts my boy about the Great Bear.

We thank the driver and rush into the airport building. When we get home, everything will be clear.

“Do you know what happened?” the Egyptian official asks me as soon as we enter the building. I don’t reply for a moment, so he keeps repeating as if helping me to realize:

“You cannot go to your country.”

“You cannot go to your country.”

I can and I will, I think. I rush to the blue screen with the departures. This will be the last time for a long while that I see Ukrainian cities on such a screen: Lviv, Kyiv, Kharkiv. I will search the blue screens in every airport, hoping the nightmare will end.

In an hour, we are the only ones left in the tiny airport of Marsa Alam, Egypt. The desperate crowd of Ukrainians left the building heading to the buses brought by their tourist agency. The Ukrainians are to be taken to some random hotel, so they won’t prevent passengers from happier countries from boarding their flights. I booked the hotel and the flight myself and had no agreement with a tourist agency. So when everyone else boarded the buses, we stayed. The airport official asked us to leave.

“You cannot stay here,” the guy in the airport uniform repeats. He likes repetition, apparently.

I explain that we have nowhere to go, but he doesn’t seem to understand.

“We had a revolution like yours in 2011; we, too, protested against injustice. We succeeded, and Russia is punishing us for that,” I said suddenly. I could also mention I wrote a book about three revolutions,7 including the one in Egypt. But war isn’t a time for small talk.

The guy interrupts me: “Shhh. We cannot talk about the revolution openly now. Okay, you can sit here near the entrance.”

I thank him, sit on the floor, and start looking for flights.

How does it feel to be stuck in an empty airport in a foreign country, knowing that the ruthless enemy is attacking the cities you love? I feel a mixture of fury, grief, and . . . relief. Yes, I also feel relieved. It seems shameful yet inescapable to feel this way, and I justify myself by thinking I’m not the only writer who has met the beginning of an apocalyptic war with something other than despair or anger.

Czesław Miłosz, Polish-Lithuanian poet and Nobel laureate, described how he felt in 1939 when Nazi Germany and the USSR attacked Poland. “The nonsense was over at last,” he wrote. “The long-dreaded fulfillment had freed us from self-reassuring lies, illusions, subterfuges; the opaque had become transparent.”

I once accidentally bought Miłosz’s book in Kraków, the city to which I am desperately trying to find tickets now, sitting on the floor in the empty terminal. The reasons for Milosz’s relief were not the same as mine, but I agree with the main point: the nonsense is finally over.

My son’s last birthday wish was never going to come true: the war he was growing up with never ended but evolved, grew and morphed into a full-scale war we have not yet seen. We are entering an open battle with Russia. It is time for everyone to call the war a war.

The season of phantasmal peace is over; everything is illuminated like this empty sunlit terminal in the middle of the desert. There are no tickets to Kraków from here. I don’t know where to go. And I recite a poem by Derek Walcott in a whisper:

. . . and this season lasted one moment, like the pause between dusk and darkness, between fury and peace, but, for such as our earth is now, it lasted long.

I guess when the world ends, some people cry, some scream, some go silent, some swear, and others recite poems. To be honest, I swear a lot too. Over time, I will also learn to laugh a lot again. The end of the world isn’t as quick as everyone imagines; there’s time to learn. Yet there are no instructions.

________________________

From Looking at Women Looking at War. Courtesy St. Martin’s Press, Copyright 2025 by Victoria Amelina.

Victoria Amelina

Victoria Amelina was killed by a Russian missile in July, 2023. She was an award-winning Ukrainian novelist, essayist, poet, and human rights activist whose prose and poems have been translated into many languages. In 2019/2020 she lived and traveled extensively in the US. She wrote both in Ukrainian and English, and her essays have appeared in Irish Times, Dublin Review of Books, and Eurozine.