Yes, But Can You Really Explain the Difference Between Morals and Ethics?

Eli Burnstein on the Subtle Nuances of the English Language

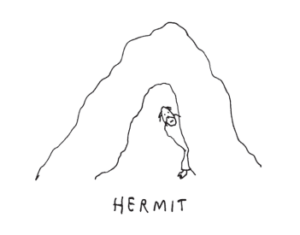

Hermit vs. Anchorite

A hermit retires from society to live alone in the wilderness.

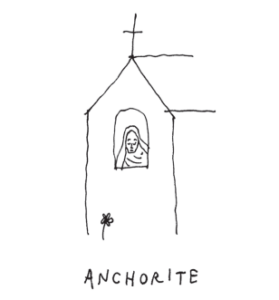

An anchorite retires from society to live in an enclosed cell attached to a church.

One lives apart. The other, within.

Eclectic Ascetics

Hermit dwellings, or hermitages, can be as simple and remote as a cave in the desert, or as developed and nearby as a detached building on monastery property.

Historically, anchorages (or anchor-holds) were attached to churches in the center of town, the individuals dwelling within them serving as spiritual guides for the community. In the late Middle Ages, female anchorites (or anchoresses) far outnumbered male ones.

It’s worth noting that during an anchorite’s walling-in ceremony, a bishop or local priest would read them their funeral rites: They were to be considered “dead to the world.”

Stylites, finally, were an early and extreme type of ascetic who would live at the top of a column or pillar for years or even decades—most of the time standing.

*

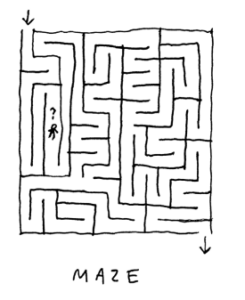

Maze vs. Labyrinth

A maze has many paths and challenges you to find the exit.

A labyrinth has one path and draws you toward its center.

One is a puzzle designed to challenge and amuse.

The other is an exercise designed to calm down the mind.

Walking in Circles

Labyrinths have served a variety of ritual and religious purposes over the millennia, from traps for evil spirits, to burial grounds, to crucibles of personal transformation and symbols of the path to salvation. Wherever they pop up, the idea, in part, seems to be that the repetitive and uncomplicated motion of walking in spiral-like formations can bring on a relaxed, even contemplative frame of mind. Hence the labyrinth’s modern therapeutic appeal.

EXCEPTION: The eponymous labyrinth of ancient Greek mythology—the one with the ferocious Minotaur in its depths—is, in descriptions by classical authors, pretty obviously a maze. Otherwise, why would Theseus need to retrace his steps with a length of thread after slaying the monster? Shouldn’t it be easy (albeit tedious) to get out?

Verdict

Greek namesakes notwithstanding, there remains a meaningful difference between a forking navigational game that’s riddled with dead ends and a winding hypnotic track that isn’t. Mazes refer to the first kind of object; labyrinths, alas, are a bit either/or.

SARAH: You’re a worm aren’t you?

WORM: Yeah, s’right.

SARAH: You don’t by any chance know the way through this labyrinth do you?

WORM: Who me? Naaah, I’m just a worm.

–From Labyrinth (1986)

*

Ethics vs. Morality

Ethics refers to intelligible principles of right and wrong.

Code of ethics

Workplace ethics

Morality refers to right and wrong as a felt sense.

Moral compass

Moral fiber

One is rational, explicit, and defined by one’s social or professional community; the other is emotional, deep-seated, and dictated by one’s conscience or god.

That’s why an immoral act sounds graver than an unethical one: One may get you fired, but the other could land you in hell.

The Fine Print

With characteristic sass, usage master H.W. Fowler notes that “The two words, once fully synonymous, & existing together only because English scholars knew both Greek & Latin [ethics being Greek in origin, morality Latin], have so far divided functions that neither is superfluous… ethics is the science of morals, & morals are the practice of ethics.”

While Fowler is here alluding to ethics as a branch of philosophy, the conceptual flavor of the word can be heard in its everyday sense as well: Whether theorized by Aristotle or spelled out in a code of conduct, ethics is morality, as it were, with glasses on.

*

Parable vs. Fable

A parable is a brief tale with a moral lesson.

A fable is a brief tale with a moral lesson—plus animals.

Tales That Teach

Fables personify animals to illustrate a point about human folly, as for instance in the fable of the tortoise and the hare. Because of their dissociation from humans, fables tend to be lighter, more ironic fare.

Parables, by contrast, feature humans, and try to convey a deeper or more complex message about the human condition. In the case of Jesus’s parable of the prodigal son, for instance, the message is that it is better to be forgiving than to be just, or that God loves sinners, or that… well, it’s complex.

A person who writes fables is a fabulist.

__________________________________

From Dictionary of Fine Distinctions: Nuances, Niceties, and Subtle Shades of Meaning by Eli Burnstein. Copyright © 2024. Available from Union Square and Co.