Writing Women's Pain: Part Two of a Roundtable

A Conversation with Alethea Black, Abby Norman,

Esme Weijun Wang and More

We asked some of our favorite writers (listed below, with their latest books) to address what it means to write and research pain and to unpack the ways in which this influences the fiction and nonfiction they write. The following is part two of that conversation, edited for clarity. You can read part one here.

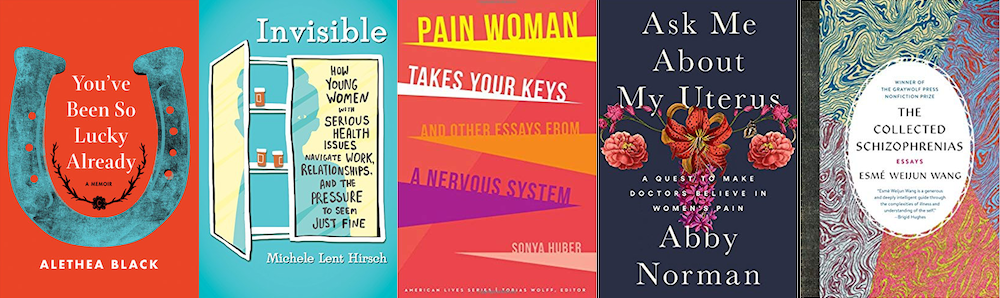

Alethea Black, You’ve Been So Lucky Already · Michele Lent Hirsch, Invisible: How Young Women With Serious Health Issues Navigate Work, Relationships, and the Pressure to Seem Just Fine · Sonya Huber, Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System · Abby Norman, Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain · Julie Rehmeyer, Through the Shadowlands: A Science Writer’s Odyssey into an Illness Science Doesn’t Understand · Esme Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias

III.

Do you think it’s a truism to talk about the redemptive power of turning pain into art, or do you think there really is something redemptive about it?

Sonya Huber: I believe writing is often a quest for redemption: redeeming and re-finding, renaming, reframing. I don’t think I’d be so compelled to write if that weren’t part of the goal and the possibility. But I don’t always know what “redemption” means or if I’ve ever gotten there. And we never know what is redemptive for other people to read. I could write something very redemptive for myself, but that doesn’t mean I’ve succeeded in creating a parallel experience for the reader. I have not cured my own pain with words, nor have I cured anyone else’s, but writing has the power to make us feel less alone, to soothe or to challenge and reorient us. To have even a slim chance of doing that for myself and for others, once in a great while, is very compelling. I also think I write just to see what is really going on in my life, to admit it to myself.

Julie Rehmeyer: One of the most difficult aspects of illness is the sense of isolation. Trying to convey the experience on the page, and to create something that would be useful to others, helped break me out of that. It was part of a more general process of moving outward: At first, my illness felt like it was just my weird little problem. Then I connected with others with ME/CFS and then mold illness, and I saw the political dimension of the problem: lack of research funding, lack of public acceptance, lack of support, on and on and on. And more recently, I’ve come to see that those problems face people with most chronic illnesses. We need a new civil rights movement. And playing some role, however small, in creating such a movement, transforms the experience of being sick, giving it a meaning so that it’s not only pointless suffering.

Alethea Black: I agree, Julie. Pain is a great motivator for change. And more and more people nowadays are being forced to live with chronic pain. At a certain point, the collective will rebel and say: Enough.

To say that writing about something can help to redeem it is probably both—a truism and also true. When a movie or a book or a play manages to deepen my understanding of something unconscionable, it makes it less unconscionable to me. Nowadays, when something awful happens, if I can just create a tiny crack of distance between the experience and myself—as if, for instance, I were writing about it—it can temper the awfulness so much.

Abby Norman: I’m sure it’s different for everyone. Probably even different for each person depending on where they are in life, the nature of the pain, its progenitor. I’ve never created anything with any hope of redemption. I’ve only ever created as an act of seeking clarity. As a child I was trying to sort out the world and the people in it who were around me. As I grew up the focus turned inward, which I think was just a natural response to adolescence and coming of age in the early 2000s where the expectation to be digitally present became unavoidable and, overwhelmed by that, I split off into the “curated” version of myself. That self was projected and well enough received that I could continue to keep certain parts of myself not just offline, but completely private—not even outside of myself.

Writing the book, then, especially the memoir portions of it, required me to unify these parts. Or really, I think, bringing out and giving up the part I’d tried to keep for myself. I wouldn’t say that integration was redemption, I wouldn’t say it was a liberation. It was hard, and painful, and scary. It has not always been rewarding and I would be lying if I said I never had a moment of regret. But where I think the redeeming quality can be found is that in doing so, I can say that I gave it all when I wrote the book. I knew that unless I could be completely vulnerable there was no point in writing it, in telling the story. I knew that I was going to take that risk without being fully aware of what it meant, just because I was far too young to understand. I still am, I think, but the process wisened me. And certainly being so ill ages you and matures you.

So, I emerged from the other side somehow less confident in my purpose or process creatively, but what I came away with was a sense of personal integrity that I hope might guide me toward a place of redeeming, of forgiving, myself.

IV.

Are there people in your life who’ll find it too painful to read the details of your illness journey? Are there people who’d never know the extent of what you went through if they didn’t have access to your writing?

Alethea Black: I don’t know that it’ll be too painful for anyone, and of course there are people who’d never know, unless they read the book. If what you’re asking is whether reading about what this was like for me will render a deeper and more intimate understanding of the experience than would be gleaned even if you’d been sitting beside me while it happened, the answer is yes. That’s the magic of writing.

Sonya Huber: I am lucky to have people in my life who say, Give me this book and keep writing, folks very willing to go along with me through the stories. My mom found it very sad, but she read it. My husband hasn’t read it, but he lives it with me. I don’t tend to share much about my experience with pain and illness outside of my writing. It’s almost the only vehicle I have. Face-to-face conversations with pain are very difficult, because people have so many preconceived ideas and, frankly, terrors, about pain that their brains are constantly struggling to “fix” and erase the experience. I think this is true for many, many life conditions; we don’t have the conversational capacity or place to put accounts of extended suffering. Suffering is seen as unacceptable in some deep way in our culture, and it comes freighted with fear and judgment, so many stories of long-term pain are not shared.

Julie Rehmeyer: In talking to people I don’t know well, I typically give a very condensed and not very accurate version, saying something like, “I have extreme allergies.” That’s something people can understand, and it paints a picture that’s closer to the reality than saying that I have chronic fatigue syndrome, which people think means I’m really tired. (In fact, sometimes acquaintances will ask me if I’m still feeling tired, and it takes me a moment to figure out why they’re asking such a bizarre question.) The distance people have to travel to understand what I’m actually dealing with is much, much too far for a casual conversation. But quite a few of my colleagues have read my book, and that changes everything—they not only understand what I’ve gone through, they see how it connects to their own experiences. And even people who have followed my saga fairly closely over the years and then read the book have said that there’s so much they hadn’t understood.

Michele Lent Hirsch: Some friends and family members who’ve known me for years learned new aspects of my internal experience by reading Invisible. Aspects there may not have been space to talk about back when my health issues were unfolding—or that I at least didn’t know there was space for. I didn’t realize what you were going through is a sentiment I’ve heard from a few folks, and it makes me think about something I write about: how even if we have warm and loving people around us, we sometimes get the sense that we shouldn’t weigh someone down with talk of surgery or cancer or pain. And that’s certainly a deep cultural issue, as Sonya said. It feels surreal and a little scary to have my private thoughts about bodies and gender and health in bookstores and online, publicly accessible. But having strangers read these thoughts isn’t as weird for me as having close friends suddenly learn how I felt a decade ago, when we were bopping around in our early twenties. I have really wonderful friends. And I’ve gotten the sense from some of them that reading my book has shifted their understanding of what it’s like to deal with health crap when you’re young. For me, it’s also made it easier for us to talk about it all in person. It feels like it’s made our close friendships closer.

Abby Norman: There are very few people in my life now who knew me before I got sick. Illness has a way of culling your social life. Most of the connections I have now that I maintain are professional and certainly what people know of my experience in that realm is quite limited. I suspect they may be somewhat taken aback by some of what’s in the book. But really, I think it’s the people who knew me before, who knew and loved me when I was well—when I was happy—who had the most difficult time reading it. Partly because a few of them lived through it all with me and had to relive it, but from my perspective, in doing so. But also because they remember, and are pained by as I am, what it was like before. And as much as I miss being well they miss me being well, too. And we are constantly reminded, as life trudges on, of how much of my life and their lives I have, and continue, to miss. My presence in the lives of others has largely been reduced to writing–either the book, or a scribbled letter attached to a baby shower gift, or a note on an RSVP to a wedding I won’t attend, or an email sent off apologizing for my absence but making no clear indication that I’ll remedy it. A social media post now and again, though I’m slowly retracting myself from any spaces that make sharing my life feel performative.

V.

Sometimes the law of unforeseen consequences has comedic effects for writers, and you write a story about your mother’s death, but some readers think it’s about the day you went shopping for a dog harness. Have you found this to be the case in your writing about illness? More so or less so than with other kinds of writing? Does writing about illness require a more ‘direct hit’ than other types of writing?

Sonya Huber: At least in my first foray into writing about chronic pain, it seemed to me that the topic pulled everything else into itself, like the gravitational pull of a huge planet. I would try to write about subjects tangential to pain, and these essays would sometimes be read as intense or very sad because pain appeared as a minor character. I think I did compensate by diving right into the subject with more directness, because I realized through reader responses that skirting the edges wasn’t really possible with this topic.

Abby Norman: From the standpoint of a reader, I think it’s a matter of taste. As a writer, and I think this comes much from me being a science writer, having been a reporter, having a proclivity toward nonfiction or fiction and prose and poetry, that I feel I can only tell stories, that I can only write, in the way that I speak. Which is to say I’m fairly direct. But I can turn a phrase! I think there are times, especially writing about such a subjective experience as pain, when you can’t be direct. Because the spectrum of human perception for that experience is so vast that you won’t reach as many people by communicating it in that pure, mechanical, sort of detached way that you might have processed it. You need to create a parallel, an analogy. You need to invite in a metaphor. I think the greatest challenge is reconciling that you aren’t alone in experiencing pain, but your experience of pain is not universal. So how do you share it in a way that both honors and illuminates your experience but doesn’t negate or shadow another? How do you reach out and connect the two in the dark?

Alethea Black: Some readers will always misinterpret things, and that’s okay. In a way, you bring with you and project your own experiences onto whatever you’re reading, so it’s always a collaborative act. Both as individuals, and as a collective, we’re always learning. If I write about wanting to get to the real root cause of my ‘mystery illness’, and standing my ground when faced with doctors who were inclined to think my nervous and digestive systems weren’t working because I was anxious—instead of the other way around—some readers will empathize with the doctors. And that’s legit. But other readers—and their ranks seem to be steadily growing—will want to know more, and will find themselves, perhaps very slowly and tentatively at first, listening.

VI.

We tend to expect illness narratives to end in wellness, but that’s not the way real life always goes. Did you accept that basic narrative structure, or did you push against it?

Sonya Huber: I couldn’t bring myself to write the narrative along the timeline of my illness. Narrative questions of cause and effect didn’t interest me. Abby writes above about writing to find meaning and understand, and I think somehow narrative expectations made me feel as though they wouldn’t deliver that meaning, at least for this subject and for me. The standard timeline structure felt like part and parcel of the abled world’s expectations; “getting better” is almost a moral obligation. And if one can’t get better, I guess you have to deliver a kind of acceptance or transcendence, which I couldn’t do either. My narrative feels very boring to me; there’s no drama that conforms to an external plot. Each day, however, is its own separate set of adventures and struggles. I wonder if there’s something about chronic illness that unglues a person from time, and that is somehow something we have to wrestle with in our books? I felt that challenge of describing altered time hovering in the background as I wrote. I wanted to take on the assumption that without external drama, there was no meaning or insight. That said, I did sort of arrange my essays in an order that references chronology but isn’t bound by it.

Esme Weijun Wang: The conditions I live with have tended to come with the notion of, “no cure.” Things can get better or worse, but they don’t tend to travel or progress in a linear way, and so the idea of an arc or narrative is a tricky one. After I won the Graywolf Nonfiction Prize, which is for a work-in-progress, I came to my editor (Steve Woodward) with a bunch of essays and a lot of confusion about how to put together The Collected Schizophrenias in a way that would feel like it had an arc—neither a chronological arc nor a Hero’s Journey, but something that made sense and would feel satisfying to the reader. Did I achieve that, in the end? Hopefully, though perhaps in an unconventional way; and even now, I see my life as getting better and worse in an extremely arbitrary way.

Alethea Black: I’m laughing because in the review of my book in The New York Times this weekend, the reviewer disliked that my rendering of chronology was not more clearly laid out and linear. And Sonya, that’s funny that you mention the idea of a person becoming unglued from time in your answer, because notions of time and how we experience it were a big part of the resolution to my illness journey. Because I never received a formal diagnosis—the tests doctors would order continued to tell them that nothing was wrong, but my body continued to tell me that nothing was right—I was forced to research my symptoms myself, while collaborating and comparing notes with some of the thousands of other people who are falling through the cracks of mainstream medicine. This led me down a rather unexpected path—toward quantum physics—and I’ve become fascinated by the idea of a relationship between human illness and the experience of time.

Julie Rehmeyer: My story did roughly hew to the conventional narrative of getting better and finding transcendence. On the one hand, that made my job as a writer easier, providing a satisfying conclusion—but on the other hand, it made it harder, because I knew that the reality was that I got lucky. I could have done everything I did, attained every insight, gone through every transformation, and still been just as sick. (And indeed, since finishing the book, I’ve had a serious setback in my health.) The idea that we earn wellness by being good people (where “good” is defined in any number of ways) is a revolting one, because it implies that if we’re not well, it’s because of our own flaws. I worried endlessly about betraying my fellow patients and myself by allowing my story to reinforce that narrative. So I worked hard to complicate that story, making it explicit that my improvement was very substantially out of my control.

Michele Lent Hirsch: My story is woven in with those of the women and femmes I interviewed, and on the whole there’s no illness —> wellness linearity. Many of us with bodies that have done unexpected things know that illness, wellness, and the ways we think about our bodies are always in flux. You can trace my growth through the book, in the ways I learn from those I meet and examine my own thinking about bodies and identity. Maybe the structure that emerges is, in the end, a sense of community.