Writing Women's Pain: A Roundtable

Part One of a Conversation with Alethea Black, Abby Norman,

Esme Weijun Wang and More

We asked some of our favorite writers (listed below, with their latest books) to address what it means to write and research pain and to unpack the ways in which this influences the fiction and nonfiction they write. The following is part one of that conversation, edited for clarity.

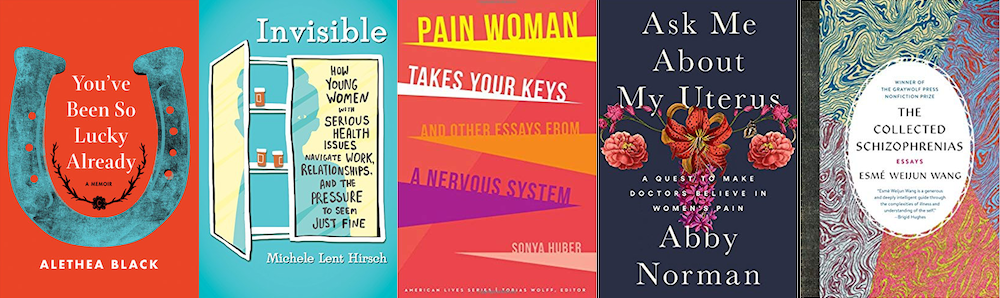

Alethea Black, You’ve Been So Lucky Already · Michele Lent Hirsch, Invisible: How Young Women With Serious Health Issues Navigate Work, Relationships, and the Pressure to Seem Just Fine · Sonya Huber, Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System · Abby Norman, Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain · Julie Rehmeyer, Through the Shadowlands: A Science Writer’s Odyssey into an Illness Science Doesn’t Understand · Esme Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias

I.

Pain is such a hard thing to describe. Not only is it subjective, but it’s notoriously vivid in real time and fuzzy in memory (e.g. pregnant women’s impressions of giving birth). Did you find the personal nature of pain to be something vexing or motivating, in terms of trying to write about it?

Sonya Huber: Trying to describe the sensation itself was one of my main motivations in writing Pain Woman Takes Your Keys. When I first began to have significant chronic pain, the personal and internal nature of the experience made it so isolating, and I struggled for words to try to share the experience with others. It was that real and ongoing need to share and connect that pushed me more and more toward language and metaphor. Once I began to get courage in taking wild leaps with language, the challenge became a compelling puzzle—and continues to be! And I think the one advantage to writing with chronic pain is that there’s always more pain, so I can check in with myself at any point to re-sample the experience.

Julie Rehmeyer: Both! Language is not a natural tool to capture internal sensations. The words at hand for describing pain—stabbing, crushing, throbbing, cramping—capture quite a narrow range of the types of discomfort humans can feel. Also, how do I convey to you a sensation you may well never have experienced? That makes it daunting, but it also feels like writers are the people whose skills are most suited to the problem.

I agree with Sonya on the power of metaphor. It probably doesn’t mean much to say to most people that my brain feels inflamed. Instead, I might describe it this way: “My brain feels like an overripe peach, bruised and delicate, its juices threatening to seep out my ears.” Hopefully that gives a visceral sense of the sensation—and offers language others can use to describe the experience.

Alethea Black: I think pain can be as ineffable and mysterious and internal as love. How to let someone else know what this sensation is like when I don’t fully understand it myself? How to make concrete what is so abstract—yet simultaneously concrete? Anyone who has sat in a doctor’s office, put her hand on what hurts, and tried to describe it with enough clarity and precision that the doctor not only recognizes the symptom (and perhaps the architecture behind it), but feels it in her own body, has, in a sense, been a writer.

Michele Lent Hirsch: I love this idea, Alethea, that anyone who’s ever tried to describe pain to their doctor has, in a sense, been a writer. It makes me think about the women I interviewed for my book. For the memoir strands, I had to try to put my own pain into words, and that was certainly vexing. But for the reported sections, I listened to the experiences of others who’d gone through illness or pain. Not quite like how a doctor listens to a patient, but perhaps as a peer listens to a peer—only I was charged with accurately portraying what they told me. Since I couldn’t rely on my own visceral memory for these reported parts, I tried to stick with the phrases that my interviewees used in the hopes of doing their stories justice. To some extent, they wrote their own stories, because only they know their own bodies. While I used some writerly techniques to coax their experiences toward the readers’ mind and heart, I wanted to honor their word choices as much as I could.

Abby Norman: From the beginning—not just in terms of the book but in terms of my life and the full spectrum of painful experiences I’ve endured—writing about my pain was really the only way for me to understand it. I’ve generally always felt the need to disassemble experiences methodically by writing about them, which allows me to process them intellectually in a way that is manageable for me. For most of my life this was a private act, and I have to admit that the choice to take it public wasn’t necessarily easy. I recognized I was, in a way, giving up my most relied upon coping mechanism in service to an issue that I had come to realize went far beyond my own experience and was part of something much larger than me, my life, and my story. And, therefore, my process. Although I don’t regret that decision, it’s been difficult to cope with the painful experiences as they continue to compound now that my entire method for doing so has become a public, rather than private, process.

But one of the gifts of having done this the very act of sharing my pain in this way has put it into a larger context, thus removing it from me in a way. It’s given me some distance that has helped me gain perspective, to begin to grieve. At times I’m miserably overwhelmed to know that I’ve not been alone in having these experiences and each message I get I feel a sense of duty or responsibility—or guilt when I can’t offer or solve anything. Other times it’s more a feeling of solidarity, of sharing, of recognizing one’s struggle in someone else. Empathy is pain familiar.

What’s been most vexing to me now, having told this story and written my way through the pain of the past… is that all I’m experiencing now I feel strangely inexperienced in. As though I’ve abandoned my methodology. Despite having written a book that’s arguably more than half memoir, I find it very difficult to write about myself now.

Esme Weijun Wang: I imagine that this is something that will continue to shift throughout my literary life, but I’ve always considered one of my aims as a writer to be the act of attempting to describe the visceral experience of pain, whether psychic or physical. In writing The Border of Paradise, I very much wanted to talk about psychosis in ways I hadn’t seen before, and my personal experiences laid the groundwork for that. It became even more important for me to be able to describe psychosis and psychic pain in The Collected Schizophrenias, my second book, which also covers some of the terrain of late-stage Lyme disease within its essays. So, in my case, my personal experiences of pain were motivating.

Sonya Huber: I was very reluctant. When I was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, I doubted my ability to make sense of what was happening in my body. Then there was the nonfiction dilemma of no clear narrative; my condition isn’t going to go away, barring some unforeseen medical miracle, so I couldn’t see a “story.” I worried about it being “too depressing” because I struggled with increased depression (kind of an extra side-order of depression on top of the depression I already had). Plus, the main action involved a lot of me lying on the couch, on beds, and on the floor, so that’s less than riveting. But then I read Sarah Manguso’s remarkable book The Two Kinds of Decay and was led to start thinking about the ways language itself could carry the experience.

Esme Weijun Wang: The Two Kinds of Decay was a very important book to me when I first got sick with Lyme. I was (and am) in awe of how well Manguso could write about physical suffering.

Julie Rehmeyer: I felt like I had no choice in this one: I had to write it. Chronic illness is rising dramatically, and we don’t yet have a rich enough literature to help us make sense of this crushing and transformative experience. In getting sick, I felt as though I were gradually pulled down the rabbit hole into an underworld I had scarcely imagined before, and to the tiny extent I had imagined it, I had sneered at it as unscientific and crazy. But once I was there, it changed my view of almost everything. Then I faced this gap in talking to people who hadn’t gone through this—it wasn’t just that we viewed things differently, it was that they couldn’t imagine that there even could be a different way to view it. So I wanted to entice my readers down the rabbit hole with me and to create in them a bit of the transformation my own perspective had undergone.

Abby Norman: I made a very conscious and sustained effort to push those feelings aside until I had completed the manuscript. I was constantly at risk of psyching myself out. I’m still reeling from the panic that ensued once I finally allowed myself to sit with that uncertainty, and fear, and reluctance. Feeling how paralyzing it is, I know that had I tried to make space for it in the process of telling this story, if I’d not hardened myself, I wouldn’t have been able to write about it. Consequently I do think there are portions of the book where my detachment is apparent, maybe in a way that is somewhat isolating—but that’s evidence, I think, of survival. Not just my determination to survive the events in the book, but the act of writing it.

I do think that since the story was very much still unfolding as I was writing it, once the book was done I was able to come away with some closure for a lot of what had happened leading up to where I am now. It’s always odd for me to step back and realize that I’m sicker now than I was at the climax of the story I told—but I’m also very aware that had I not told the story when I did, because of how my ill health has progressed since, I may have missed my chance. I think I would have preferred to tell it some years from now, when I had more distance and life experience and perhaps had become a more refined storyteller. But I think the truth is, the moment was right. So, I’m thankful that I was given the opportunity and that it lined up with some of the last years of full-function I had.

Alethea Black: I think part of my reluctance stemmed from the fact that writing about my illness would mean writing about myself, and I usually prefer to write about other people. So there was that initial hurdle. At first, I tried to give myself some psychic distance from the material by writing about my health struggles in the second person (a solution that’s so natural, I’ve also noticed it in the work of Heidi Julavits and Joshua Cody). But after a while, too much second person becomes a bit tedious, so I wound up with a hybrid creature—some parts written in first person, other parts sliding into second. In the end, I’m glad I gave in. One way or another, this material was going to have its way with me.

Julie Rehmeyer: There’s no question that it’s scary to expose these most vulnerable aspects of our lives, particularly when we’re our illnesses are so often dismissed as being all in our heads. Part of my motivation was doing so was to say, “You think this is psychological? OK, instead of picking on everyone else, come pick on me. I’m going to write my story as honestly and transparently as I can, showing you a huge amount about how my psychology works. Then you can see if, in light of that, you’ll still accuse me of that.” Of course, a few people have, but it’s also opened some people’s eyes. Vulnerability can be disarming.

II.

Did writing about illness—or while coping with illness—change your work habits at all?

Sonya Huber: Writing about illness helped me to see and acknowledge the way in which pain had woven itself through my days, and I think seeing my reality on the page—and then working with it, reflecting at a distance—helped me to develop more compassion and understanding for myself. I was very depressed because I could no longer work the way I was accustomed to working, in long great swathes of time, and I was so angry at myself, almost determined to figure out a way to “push through” and access my previous methods of work through force of will (and… nope. That didn’t work). Describing my reality helped me see what I was up against, and then in that description I began to see I was still working, but in a different rhythm. Now I can look at certain ideas and sense I don’t have the energy for them, but the limitations have introduced a creative constraint that has forced me to come up with other forms, methods such as writing in short bursts, stitching together any essay more slowly and having more faith that something will cohere eventually.

Julie Rehmeyer: I’ve had to learn to just write when I can and forgive myself for not doing so while I can’t. Happily, I was doing pretty well while writing the book. But as I researched the science—and especially while interviewing mainstream, skeptical researchers—I felt as though I had to kind of split myself in two. My central problem is mold hypersensitivity, which such folks typically maintain doesn’t exist. At one point, my nextdoor neighbor’s house flooded, spewing mold spores into the air, and so I was sitting on the floor of my bathroom, the cracks in the door sealed off, with air purifiers blasting, talking to one of these guys as he told me I had to be crazy. I kept asking him about the holes in his scientific argument, restraining the personal implications of what he was saying. I did come out to him as one of those “crazy moldies,” but I still felt as though I had to hold these two aspects of my identity—a scientist and a patient—separately, in a way I don’t ordinarily do.

Abby Norman: All aspects of my life must be constantly amenable to change. I’m a creature of habit and linear living and schedules and checklists, so this has been one of the most difficult aspects of chronic illness for me to accept. Particularly where creative work is concerned because not only has it long been my main source of identity, but really my one true and boundless joy. To feel as though that’s all been lost to me has stirred up in me something beyond depression—a real existential crisis, I think. Being ill has rendered me, and my life, totally unrecognizable. I have tried to exercise stoicism in the face of this, but the sicker I’ve become the less able I am to conceal how much it frightens me.

I’m very much still in the process of figuring out how to work like this. If I can work like this at all, really. It’s the quintessential cautionary tale: don’t tie your entire identity to your work, because should you be forced to be without it.

The fear for me, always, is that I will somehow slip or slink into an identity that is tied to my illness. Sometimes it seems inevitable only because it takes up so much of my life—as it must, if I’m to survive. My attempts to avoid that have rendered me somewhat hollow, which may be why writing about myself seems difficult. I am only “myself” in the moments where my illness or pain isn’t making some kind of demand on me. There are little moments in the day when I connect to something else—art, music, literature, film, nature—when I allow myself to come back. Otherwise, I generally find it necessary to be as far outside my body as possible.

It’s in those fleeting moments when inspiration strikes and I’ve just had to accept that for now, all of that must be carefully filed away and hoarded. I take some pride in organizing it. I think I actually find it a joy and somewhat soothing, actually. I can’t work the way I want to right now. Some days I really can’t do much at all other than breathe and watch the sun pass through my window. But there’s still a part of me that thinks—someday, someday. And I want to be prepared. So for now I find myself focusing on the act of seeking and acquisition, which I’m trying to appreciate as being a valid, important, worthy part of the work. Of the creative process. As much as the act of writing, maybe more, since the survival of my spirit seems to be dependent on it. When your life seems to be little more than a litany of painful experiences, there’s something fortifying about continuing to grasp. About telling yourself, “I’m getting ready, I’m getting ready.”

Sonya Huber: I just wanted to second Abby’s point about being a creature of habit and schedules, and then having an illness throw those schedules awry—and also the point about being outside my body for a good part of the day. Both of those insights are so true.

Alethea Black: Yes, they really are. I’d like to third her point! It’s so true.

I’ve been told that my writing style is “high-energy,” and I need to feel high-energy in order to write well. Whether this means coffee beforehand, or a walk on the beach, or listening to a favorite song, or some stand-up comedy—I have to feel my pilot light on high before I write.

At least, that’s what I thought before I got sick. After being sick, that attitude changed. I started to think that all I needed in order to write well was to be awake (and not in too much pain) and sitting at my computer. The work itself, once I get into it, will lend me the energy required to write it. The work itself is the pilot light.

Esme Weijun Wang: I could write an entire book about this, but the most tangible example of how much my writing process has changed is in how much I rely on my phone or iPad Mini now, as opposed to my laptop. I wrote my first book in great big, long spurts, often crouched at my laptop for up for up to six or seven hours at a time. I wrote most of my second book while lying in bed or on a couch, tapping away on my iPad Mini. Writing is already exhausting in so many ways, but to remain upright while doing so–that adds an extra challenge for me.

What Abby said here: “I’m very much still in the process of figuring out how to work like this. If I can work like this at all, really. It’s the quintessential cautionary tale: don’t tie your entire identity to your work, should you be forced to be without it” resonates so deeply for me. I’m in a better place with my chronic illnesses right now than I have been in a while. At the worst of it, though, I’ve been terrified that I would not be able to write anything, let alone a book. The idea of production and productivity being tied to my self-worth is an ongoing thread for me—there are times when I haven’t been able to do anything but lie in bed and try to focus on something other than pain. There are times when suffering and pain overwhelm everything, even love, and that still scares the hell out of me.

Michele Lent Hirsch: I included lines in my book from one of Esme’s essays—one that centers on this idea of productivity being tied to self-worth, and the fear that many of us—we perfectionist writer types—have. This fear that we’re being lazy because we can’t work the way we used to, or the way others who don’t have health issues expect us to. Unlike some others here, I’ve never been a creature of habit. I’m the kind of person who wants to walk home from the subway a different way each day because I want to see different streets and not get sick of a routine. So I think that health issues have changed the way I work not because they jolted me out of some specific habits—since I didn’t have many of those to begin with!—but because they’ve forced me to listen more to my body, and to try to not judge that body’s needs.

And writing about illness affected my writing habits, too, in the sense that I had to take a lot of walks and try to tell myself that it was okay to proceed in a more jagged, start-and-stop way through the passages that were especially difficult to write. After I’d type a few lines about my own near-death experiences, say, or about the ways doctors abused some of the women I interviewed, I’d need to take a walk, take a break, share conversation with a friend, take days off, reset. Sometimes I could bang out a lot in a day, and sometimes I could only write two lines, because I’d squeezed those lines out of an overwhelming or upsetting experience.